Photographic Adventures with Edgar Degas

Published in the catalog Greetings From LA: 24 Frames and Fifty Years 2016

I remember having experienced a great feeling of calm on reading Hegel in the impersonal framework of the Bibliotheque Nationale in August 1940. But once I got into the street again, into my life, out of the system, beneath a real sky, the system was no longer of any use to me: what it had offered me, under a show of the infinite, was the consolations of death; and I again wanted to live in the midst of living men.

Simone de Beauvior – The Ethics of Ambiguity

Do not wait for the last judgment – it takes place every day.

Albert Camus

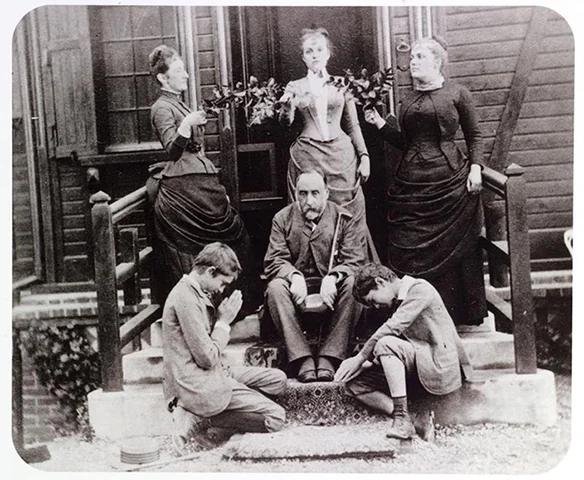

The Apotheosis of Degas Edgar Degas 1885

The photography of Edgar Degas, mostly in the form of duotone and tritone plates, was never exhibited in his lifetime, as these images first came to light, at least to the larger general public, during a traveling exhibition in the late 1990's put together by the National Library In Paris. The photographs revealed a different Degas to the artist we thought we knew - from his mastery of the master drawing to his modernist framing, from his obsession with young dancers to his ability to find the right pose - both casual and classical - that could seemingly open up the world of the 19th century to us as clearly, and as beautifully, as Zola, George Eliot or Proust. That Degas we knew - perhaps too well - but there was another person that was revealed to us through his use of photography - a sarcastic, smart-ass, subversive artist, playing critically with images. The photographer Degas speaks eloquently about his own time, and ours too by default, and it is that Degas that is the subject of this essay.

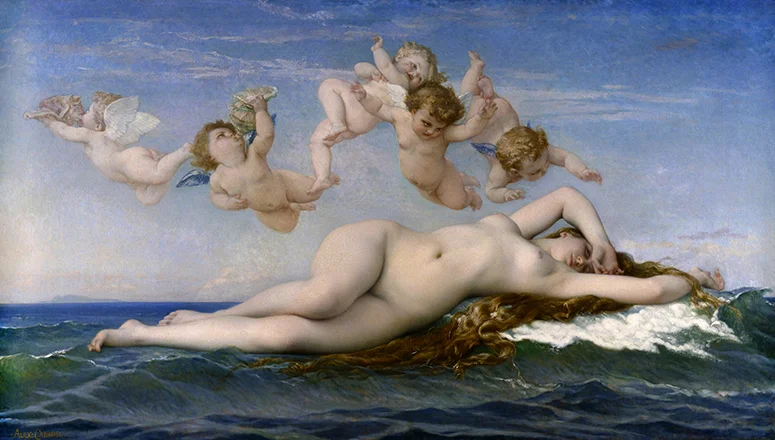

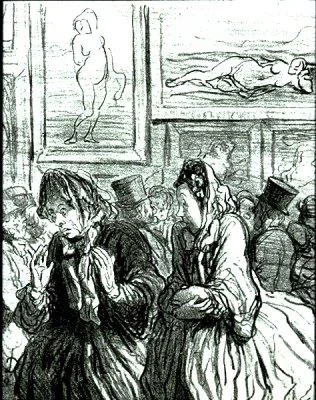

In the late 19th century, at the height of the popularity for academic art and neoclassical tableaus, models were regularly seen in the galleries and the salons posing as “Venus” or “Aphrodite” in contorted poses that signified "Classical," thereby legitimizing, or putting the nudity into quotation marks. These turgid tableaus were not only fashionable but virtually signified Fine Art, or High Art, in contrast to the “lower” arts such as design and illustration that were for the masses. Although in the time period many people in all classes and walks of life read the satirical illustrative press, such as Charivari in France and Punch in England, because their sharp, irascible, sarcasm, and sexy graphic design, was widely popular.

On the other hand the popularity for the stodgy, classical tableaus within the upper classes and the ruling elite would only be shattered in the following century by WW1 and early modernist art - a two front fragmentation bomb from which neoclassicism never quite recovered. In any case the enthusiasm for these neoclassical tableaus was often feigned and affected - in a similar manner to today when members of the upper classes must attend operas or art openings, and dissimulate enthusiasm, when they are in fact disinterested and bored. When neoclassicism did come back, very strongly, after WWI - for example with Picasso - it was in the guise of having absorbed a Modernist “consciousness” but simultaneously making an effort to reach back into the history of art’s many past lives and plunder them for dividend.

Edgar Degas’ small photograph, The Apotheosis of Degas (1885), is the first call to arms in that long battle. Degas’ work is a brilliant, ferocious re-creation of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’ The Apotheosis of Homer (1827). Werner Hofmann calls the image “… a joke with several layers of meaning which were long overlooked because Degas hid them behind his ostensible admiration for Ingres… with this self-mockery, Degas opened up a new dimension for photography…”[1] The image is the first work of photographic criticism directly aimed at the art establishment of his time – what Degas termed “the art police.”(2) The work is clearly satirical in a manner that we don't normally associate with Degas - it is maybe more in keeping with Toulouse Lautrec or Honoré Daumier who did go in for satire that was often outspoken and unequivocal. More to the point Dega's satire comes to us not as a painting, a lithograph or a drawing but as a photograph - a snapshot that mimics Neoclassicism - what is Degas up to?

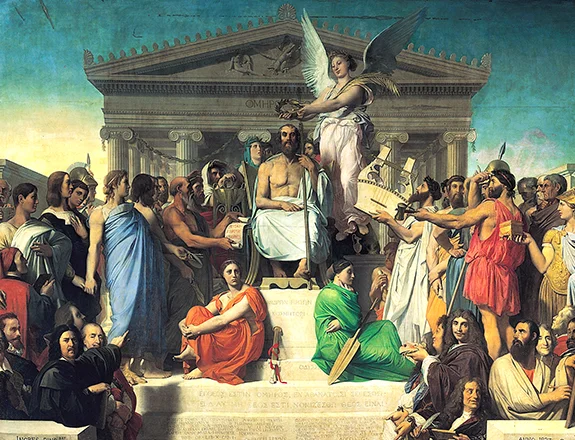

Let's start with the subject of Degas' satire. Ingres’ painting shows the great men of various centuries such as Dante and Moliere in heaven placing a crown of laurels on the balding head of Homer. The bodies in Ingres’ work are perfectly sculpted idealized figures, which would have surprised the family members of many of the assorted greats, as the physiques and gestures of the participants do not come from any reality regarding antiquity or the people portrayed. The everyday life of the classical world is something that we can glimpse, if we are so inclined, in the writings of the historian Tacitus or the works of Petronius or Sappho – all writers who were there and eloquently describe what they experienced, each in their own way. What we have with Ingres’ painting is fundamentally an illustration of 19th century academic conventions of classical antiquity as a state of mind - a conceptualized idealism of platonically "perfect" architecture, nature, and human bodies, all in harmonious balance. Some of these idealized forms were based partially on misunderstandings; for example the Hellenic Greeks and the Romans after them did not favor white unpainted marble. Quite the contrary, they loved garish contrasting colors and, of course, highly sexualized sculpture and painting. The 19th century French platonic formalism was an Arcadian fantasy that was politically as well as aesthetically motivated.

The Apotheosis of Homer Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres 1827

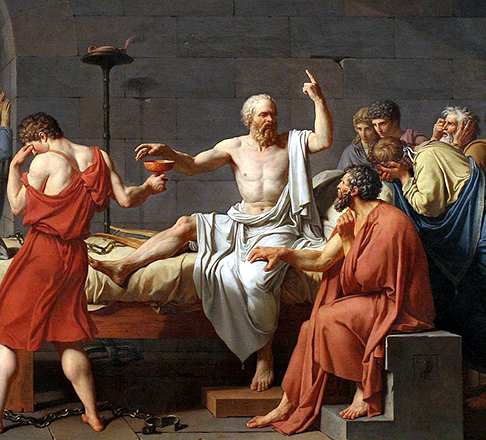

Neoclassicism's conventions started with a radical revolution about half a century before Ingres. In the "age of reason" Jacques-Louis David’s paintings staged a mythic heroism that caught the imagination of many critics, from Denis Diderot in his time to Michael Fried in ours. Yet from David’s highly theatrical heroics to the mannered self-consciousness of Ingres and then a little later the labored kitsch of William-Adolphe Bouguereau is but a short step of less than one hundred years. In Ingres’ painting all the hallmarks of neoclassicism are in place: The complex hierarchical order, the idealized harmony of opposites, an orchestration of differences with subtle narrative clues linked to classical literature, a high degree of conceptual rigor in the deployment of archetypes, metaphors and symbols, and perhaps most important of all, easily read emotional cues that favored heroism, traditional values and sentimentality.

That the ruling elites would champion such an aesthetic system is borne out by the fact that the French government supported the artists, and institutions, that favored neoclassicism from 1789 to the early 20th century, when that aesthetic system collapsed due to the emergence of the new technological/electronic age and the catastrophe of WWI. That is several generations of support for a system that the states within Europe, and their colonies, perceived as fundamental to how viewers perceived the past and the present as it was represented in various books and paintings. Therefore we can assume that this idealized image was integral to the preservation of the state. It is no coincidence that Ingres' painting was meant to hang in one of the ceilings of the Louvre - then not only a museum but a government building that housed various offices, including the treasury - an anomaly that persisted until the 1960’s.

Tableau with classically sculpted bodies in Socrates 1787 Jacques-Louis David

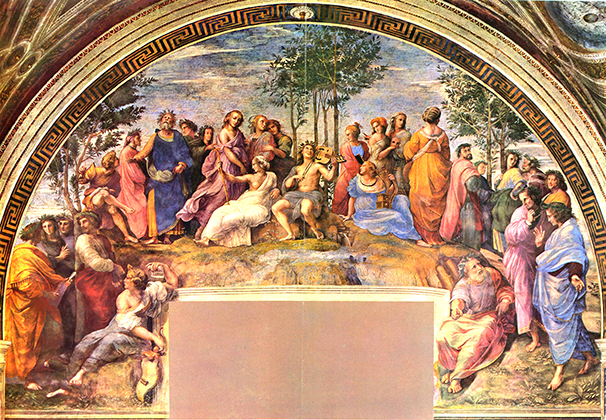

The Parnassus 1511 Raphael

As is to be expected Ingres’ vision of heaven favors the Roman Imperial style of architecture. The painting is based on Raphael’s Parnassus (1511), a wall mural decorating one of the palaces in the Vatican. Raphael’s ambitious fresco depicts a heaven-like Parnassus (a center of poetic or artistic activity) inhabited by famous cultural figures from the past, both mythic (9 muses) and real (Homer), in a theater like setting. In Ingres’ Apotheosis - a word that means "to turn into a God" - Raphael himself stands on the far left, hand to his heart, signifying in the language of academic painting his earnestness as he is experiencing some profound emotion. Everyone, including King Charles X who commissioned the painting, appears to be in deep thought, posing for an "official picture." Charles X would be deposed in 1830, three years after the painting’s completion, not because of Ingres’ work, but through ineptitude and the mishandling of finances due to colonial misadventures, the most expensive and deadly being the conquest of Algeria as a French colony – a prize that the French would be hard pressed to surrender as the Algerians won back their independence only in 1962 after another brutal, drawn out war.

Photographic staging carefully thought out - including the man half in and half out of the picture on the left in Place de la Concorde Edgar Degas 1875

In the summer of 1885, Degas was staying in Dieppe with his childhood friend, Ludovic Halevy, and his family. The artist had depicted Ludovic a number of times over the years, most spectacularly in his brilliant Place de la Concorde where we see Halevy and his two daughters crossing the nearly empty square. This is one of the first paintings to consciously use the off center framing, with subjects cut off at oblique angles by the frame. This was a formal quality that was ascribed to photography's snapshot aesthetic. In the artist’s black and white photograph children place some branches from nearby trees near Degas' head. The Apotheosis of Degas was art directed by Degas, but was actually taken by Walter Barnes, a protégé of Degas. Three women (the fact that there are three would make them muses in the language of neoclassicism that Degas is satirizing) hold branches, standing over the seated Degas, while two boys half-kneel by his feet. In 1885 the artist was sixty, but he looks much older and worn out, melancholic, impenetrable, and lost in thought. He is posing with his hat upside down between his legs as if it were a basin.

Degas helpfully performed a critique of his own photograph in a letter to Halevy: “My three muses and my choir boys should have been grouped against a white or pale background, the costumes of the women in particular are lost. And the figures should also have been closer together.”[3] Degas’ criticism is formally sound but he does not point out any of the great subtleties in the picture. The upside-down hat between the artist’s legs creates an ellipse that mirrors the crown of laurels above his head, creating a visual relationship that is funny as the bowler hat - a sign for bourgeois respectability - becomes a toilet. Degas is, in effect, satirizing the perfectly sculpted bodies in Ingres’ painting by suggesting that such bodies are beyond the physical/animal act of producing shit – because they are not real. The ubiquitous bowler hat would become an ironic moniker of faux respectability in the coming century for artists like Magritte, and later still for Hans Richter in his wonderful surrealist film Ghosts Before Breakfast (1928). Degas seems to have intuited the whimsy in the bowler as a prop early on.

Enormously successful painting in its day: The Birth of Venus Alexandre Cabanel 1863

Degas’ image is quietly revolutionary. It is one of the first breaks made by an artist using photography that visibly attacks the art conventions of his time. Degas was not alone. Emile Zola and Heinrich Zille were two artists who used photography to both document their moment in time and space and to thereby attack the fantasy art of their time - in Zola’s case this act of aggression was very conscious, in Zille’s case it was only a byproduct. The work of these artists using photography is the first opening that allows us to see how some people really felt about neoclassical art but were not free to express because it went against social conventions and institutional norms within their own class. Not surprisingly one catches glimpses of what people really felt in the popular illustrations of the time seen in newspapers and magazines, the caricatures, graffiti and popular songs of the period.

There is one very funny example from Honoré Daumier in Charivati – one of the most popular magazines of the time - its relatively inexpensive price meant that it could be purchased by working people. Two women dressed in contemporary clothes – that is with many layers covering the whole body except for the face and hands - are in a salon showing paintings of naked women idealized to conform to the tastes of the period and then placed in an Arcadian or classical landscape to italicize the nudity and put it within the context of “ Fine Art” – that is to transform them from naked to nude.[4]

This Year Venuses Again! 1864 Honoré Daumier

One of the women in Daumier’s drawing complains, while throwing her arms up in the air in disgust: “This year Venuses again…always Venuses!” Daumier’s genius was clearly that he had a great ear to match his observant eye. The women know what art critics saw but refused to acknowledge - that the "Venuses" were there for the titillation and amusement of the men, not because of their props or Arcadian setting. We see the same sorts of absurd bourgeois efforts in films and television today - to much the same sorts of wizened retorts from women who have seen it all. The popular drawings of the period tell us that Degas in his photograph was working within a well-established satirical tradition, but one that came from the bottom up, that is, from the streets, the cafes, the laundry shops and the bars – not from the academies, the gentlemen clubs or the art salons. The Dadaists and Cubists would a short time later – within Degas’ lifetime - explore these conventions of realism and institutional norms at some length, and in a sense knock the doors off the hinges, but in 1885 no one ridiculed the ruling elite publicly, for to do so was suicide. Again it is not so different today. Looking at this image is like seeing a whole century as if for the first time. It directly confronts the empty masks of the great men in Ingres’ pantheon, and the emperor is not just naked, he’s out of touch.

Ingres’ fantasy heroics would, unfortunately, play themselves out in the following century beginning with what was called “the war to end all wars” in 1914, as artists made advertising posters to promote patriotism and militarism using neoclassical motifs. The countries that participated in the many wars of the 20th century, large and small, might have hated each others politics but they all loved neoclassicism and used it to promote their military efforts. In terms of aesthetics they all seem to have agreed that neoclassicism was the way to reach the masses emotionally and move them to accept undertakings that would probably not be in keeping with their self-interest. It would be interesting to know what the artists of this period would have though of the use of neoclassicism to promote war on a massive industrial scale - Ingres never lived to see it, Degas did, but what he thought was not recorded.

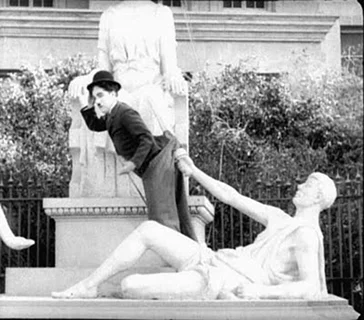

Charlie - a street person - wakes up on a neoclassical statue in City Lights Charlie Chaplin 1931

We can see already in Degas’ image the brilliant satires of the 20th century that was just around the corner with same sense of sarcasm and class consciousness. In Charlie Chaplin's City Lights (1931) the film begins with some pompous, overdressed politicians about to dedicate a heroic neoclassical tableau of life size statues, but Chaplin has been sleeping on one of them (a woman with outstretched arms) because he's homeless. As he descends a neighboring statue with sword in hand, it skewers Chaplin by the seat of his pants, leaving him dangling and helpless - he tips his hat acknowledging the crowd and in effect greets us, the audience, to his film. In Duck Soup (1933) The Marx Brothers made fun of the herd instinct of American patriotism, and musicals, as Groucho Marx, the president of Freedonia, dances with a group of women performing a classical ballet - but his cigar in hand and sarcastic expression totally undermine the classicism and bring it crashing to the ground - even some of the ballet dancers had to laugh. In both of these cases classicism is being skewered, but Degas was there first. Unlike contemporary pastiche versions of neoclassical art such as Bruce Nauman’s Self-Portrait as a Fountain or Jeff Koons’ Llona’s House Ejaculation, Degas went much further and took greater risks. This is because Nauman and Koons have italicized their photographic efforts, making them "Art" as a matter of course. Degas' photograph emphasizes its homemade snapshot aesthetic keeping those italics at a distance. Degas' work is in some sense a family picture - and as with any family picture, the primary risk is that you will look stupid and make a fool of yourself. Degas is the perfect foil for his own satire. The irony works on all fronts because he gives us an alternative vision to Ingres’ massive painting that critics have missed, perhaps because it is too obvious. Put simply this is a picture of people who loved each other and liked each others company and wanted to make art together for the pleasure of it, to surprise each other and give each other pleasure. They are the friends and children who were as close as Degas, the shy bachelor, (one aspect of his complex personality) would ever get to having a family.

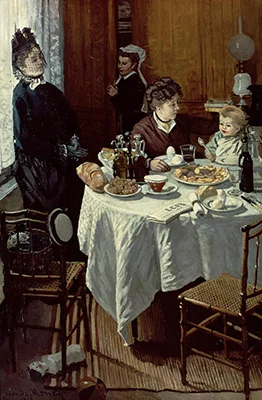

As a counter to Ingres’ imperious twelve foot tall ceiling, it presents a small picture that you can hold in your hand. Ingres’ work is about the presumed eternal power of certain classical conventions of visual presentation, and what Degas is suggesting as an alternative aesthetic is the snapshot. In effect he uses his own intimacy with his friends, and the medium of photography in an impromptu manner to talk about the distance between our mortal life here on earth and the heroic timeless ideals of Ingres’ picture or any aesthetic system such as neoclassicism – particularly its virulent 19th century model - that seeks to explain reality by fitting it into a hierarchical system of knowledge that presumes to be beyond everyday life. This is why he needed photography. It couldn’t be done as a drawing or a painting as it wouldn’t have the same emotional charge. What Degas was after was the love that you live out in the company of friends and family on a daily basis – a routine of love – something that cannot be extrapolated from a concept or theory, it must be physically experienced and improvised over time as a transitory experience.

Classical Ballet with traditional poses - but there appears to be something wrong - Duck Soup 1933 The Marx Brothers

This love, that is depicted in the snapshot, challenges death and oblivion, but does not reject it, as does neoclassical art that finds an escape clause in the contract; that is, a heaven, a place beyond the reach of transformation, decay and death. Ingres ingeniously conflates Bible illustrations with depictions of pagan classical antiquity that conform to contemporary (1827) tastes. That such a heaven, once it is “realistically” portrayed would be bound to historical details (such as the Roman architecture of the imperial period), is the crack in the foundation of neoclassicism from which the beautifully rendered edifice could never recover. Neoclassicism required a suspension of disbelief that was not tenable, once one understood the absurdity found in the details. Neoclassical art demands this suspension of disbelief– almost as an extension of religious belief itself - but like religion it cannot stand the scrutiny of historical investigation, nor an anthropological dissection of the details that make up the whole. Once the lights are turned on the masks, the sets and the costumes are revealed and the illusion is shattered.

In this respect it is helpful to keep in mind that what 19th century critics and collectors most despised about Impressionism (in some cases quite violently) was not its visible brushwork and bright palette, since these things had already been seen in the work of Gericault and Delacroix; nor the simple, quotidian subject matter that avoided heroics, since that had already been seen in the work of Corot and Millet. What they hated was the transitory aspect of the images, once Impressionists fixated not only on shifting patterns of light, but on evanescent quotidian moments that would shortly be gone forever. A wonderful example is provided by Claude Monet in The Breakfast (1868), a painting of Madame Monet enjoying breakfast while her workaholic husband seems to have pulled aside his chair and painted her before setting down to enjoy his own. For art lovers who wanted their masterpieces to reflect “eternal values,” Monet’s breakfast painting was a slap in the face - and Monet knew it.

The immediacy of a snapshot using oil paint in The Breakfast Claude Monet 1868

Just as Monet beautifully mimicked the fugitive immediacy of the snapshot, some photographers were, conversely - or perversely - mimicking the effects and the motifs of neoclassicism through, often labored, technical manipulation in the darkroom. This group, who came to be known as Pictorialists, carefully followed the rigid program of composition laid out by neoclassical painting in order that their photographs might be considered fine art as a matter of course. Some photographers like Gustave Le Gray took landscape photographs that perfectly mirrored the conventions of framing and soft focus peculiar to painting. Ironically Le Gray had to travel to the actual places that he photographed at great expense and physical danger - something that painters would have to submit to only if they wished it – a situation that ultimately bankrupted him. Others like Oscar Rejlander or Henry Peach Robinson took portraits that mimicked the effects of 19th century portrait painting – including Ingres – going so far as to create elaborate collages done in the darkroom from dozens of negatives exposed on the same piece of paper – dodging and burning to eliminate the seams and the formal effects of the collage.

As an example let's look at Henry Peach Robinson’s Fading Away (1858), Sentimentality here comes to the forefront to create a facile illustration whose theatricality is referenced in the partially open curtains. The scene was, of course, staged for the camera over a period of time with not all of the actors being present in the room at the same time. The title of the work is meant to act as the trigger mechanism that allows the sentimental narrative free reign over the image so we may then successfully "read" all of the players and their stories correctly. The characters in Robinson's drama, are unfortunately very quickly reduced to highly organized and symbolic tableaux vivants, archetypes that become merely a part of the symbolic order being illustrated, and it is this that becomes the central focus of the work rather than the individuality of the people involved, or the emotional content of the narrative. Unfortunately archetypes more often than not reduce complex realities to the simplicity of an essence – a concept – that organizes the world for us and reduces it to a cliché.

Several negatives were used on the same paper to create the tableau setting in Fading Away 1858 Henry Peach Robinson

Let’s compare this image to HonoréDaumier’s brutally realistic drawing Flu Epidemic from 1858 that depicts a young family with a baby in a tram, the mother concerned and with a sense of tragic foreboding, the father lost in helpless reflection, and most poignantly the baby looking out at the world in sheer incomprehension, terror, and pain. The great photographer Felix Nadar suggested that in the future people would find the drawings of Daumier impossible to believe because his realism would be mistaken for grotesque exaggeration. In fact this is exactly what has happened. Daumier in our time is now taken to have been only a caricaturist prone to exaggeration for the sake of a laugh. Nadar, his contemporary, had a different opinion: Daumier “decisively cuts out these early effigies of bourgeois, janitors and bankers, creatures as strange as Etruscans…(but) which coming generations will refuse to believe in, even though they are, alas!, and will remain, the perfect, daguerreotyped copy of real life in our “Belle-Epoque.”[5] In Nadar’s very modern use of quotation marks to signify an ironic overlay of meaning one can already sense the biting sarcasm of “Belle-Epoque” – clearly asking, along with Daumier, belle for whom?

Shown first as a lithograph in a magazine - not an art gallery. Bus During a Flu Epidemic 1858 Honoré Daumier

Let's see how the "realism" of Neoclassicism could easily become a political weapon. With The Snake Charmer (1879) by Jean-Léon Gérôme homoerotic sensuality is dressed up as ethnographic realism. As Linda Nochlin, the art historian, has pointed out, the work says much more about French colonial obsessions with the "Orient" than it does everyday life in Constantinople, where Gérôme traveled in 1875.[6] This is an obsession that would cost thousands of lives in Algeria and elsewhere in the Middle East where the French ruling elite attempted to bring the native population to heel. Gérôme's young boy, seen naked from the back, is playing with a deadly snake, while an old bearded man plays a fipple flute, as some wizened warriors wearing turbans lounge against a wall of beautiful blue tiles. The variety of clothing and weapons from the men, all from competing tribes and from different time periods, is completely unrealistic, undermining the highly polished realistic rendering - telling us clearly that Gérôme is not interested in depicting any kind of reality but is, in effect, treating realism as a formal quality to be manipulated for its emotional effect. The scene depicts the motley crew of men as savages huddled on the floor displaying mostly medieval weapons - a group that could easily be overturned by contemporary (1879) French forces. The prized boy, with his snake routine, would then become the provenance of the French state, to amuse the elites and their friends. To possess this sensual boy, who holds the deadly power of nature in his arms as if it were a harmless toy, would inflame the minds of many within the ruling elite, letting their own self-interests and fantasies dictate the course action. But Gérôme did not create this idea, this hunger, this dream - he merely expressed what had lain unconscious - or semiconscious - within the minds of his viewers and turned this fever into an image that was dressed up - literally and figuratively - as “realistic.”

Let’s do a thought experiment and briefly imagine what Ingres might do if hired to illustrate love for an aristocrat’s chateau. One can see the winged cupid, the suggestive Venus gloriously naked in a pose borrowed from antiquity – or perhaps Botticelli’s Primavera - the various arcane references to classical stories of love scattered across the canvas, the perfectly sculpted bodies going through the same tedious poses that would show off their torsos (and Ingres’ rendering skill), the landscape in the background borrowed from one of Titian’s erotic paintings and the narrative lines deployed like a battle plan. Do we need to ask whose love this would represent? In Ingres the clear idea always superseded the messy reality. The word apotheosis means to turn into a God and Ingres along with Charles X clearly had ambitions in that direction. Their ticket was a big painting that linked them to Homer via Raphael, and that linked French aristocratic architecture (the Louvre) with the religious architecture of the Renaissance (the Vatican). With all of those references and advocates a welcoming entrance into heaven was surely a foregone conclusion. In effect they earnestly believed in the fantasy that they themselves had created.

The snapshot aesthetics that Degas was experimenting with were then new and untested, and other contemporaries like Emile Zola, Jacques Henri Lartigue, Jacob Riis and Nadar experimented with photography (in very different ways), but unfortunately bad health and deteriorating eyesight limited Degas’ future as a photographer. It is difficult to imagine what he might have achieved in this medium had he been able to take pictures until his final year (1917) but this photograph, taken with the help of his friends Walter Barnes, Ludovic Halevy and family, gives us a tantalizing hint.

Degas’ laurel/basin/hat held between his legs is the earthbound sign of a more mundane heaven: having fun with your friends one summer afternoon and making art that made your friends laugh. The Apotheosis of Degas consciously attacks not simply one artist’s silly, pompous painting but a whole tradition of state sanctioned, official art that had become an empty, bloated formula - empty of contemporary reality but bloated with symbolic meaning that evoked an imaginary afterlife and reinforced the status quo in a single apparently seamless tableau. Ingres’ painting is a vehicle for fantasy that insidiously concealed in its highly rendered realism much more than it showed. Barnes and Degas’ The Apotheosis of Degas is a work of modern art that exposes the aesthetic, moral and political bankruptcy of that fantasy - in effect it shatters that world and opens a small crack - an opening the size of a camera shutter - into a world we recognize - it is the world we live in today.

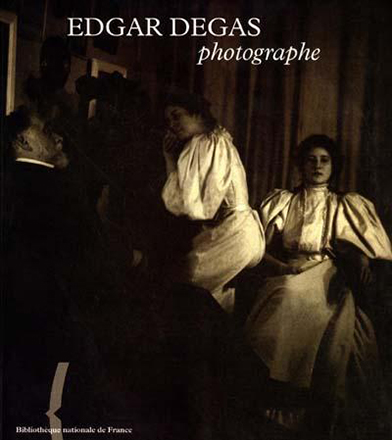

Degas (on the left) with his family posing for a picture - the cover to Edgar Degas Photographe published by the Bibliotheque Nationale de France

[1] Werner Hofmann, Degas: A Dialogue of Difference, Thames and Hudson, 2007.

[2] Hofmann, Degas: A Dialogue of Difference

[3] Francoise Heilbrun, Musee d’Orsay: Photography, Editions Scala France, 2006

[4] Kenneth Clark, The Nude, Princeton University Press, 1972

[5] Maria Morris Hambourg, Nadar, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1995

[6] Linda Nochlin, The Imaginary Orient, from The Politics of Vision: Essays on 19th Century Art and Society, Icon Editions, 1989