Antonioni's Orgy: Zabriskie Point

Published CINEACTION 2011

The 1970's was the decade when the 'glorious thirty years' of postwar reconstruction, social compact and the developmental optimism that accompanied the dismantling of the colonial system and the mushrooming of the 'new nations' was falling into the past, opening up the brave new world of erased or punctured boundaries, information deluge, rampant globalization, consumer feasting in the affluent North and a deepening sense of desperation and exclusion in a large part of the rest of the world arising from the spectacle of wealth on the one hand and destitution on the other. We may see it now, with the benefit of hindsight, as a genuine watershed in modern history.

Zygmunt Bauman - Liquid Times: Living in an Age of Uncertainty

…your art consists in leaving the road of meaning open and as if undecided – out of scrupulousness.

Dear Antonioni Roland Barthes ©Editions du Seuil Translated by Geoffrey Nowell-Smith

Poster Zabriskie Point 1970 Poster

CONSCIENTIOUS OBJECTION

Zabriskie Point began production in July 1968 and was released by MGM in February 1970, but its birth was during Michelangelo Antonioni’s trip to the US to promote Blow-Up in 1967. During the promotional tour he had read a story about a young man in Phoenix, Arizona who had stolen a private plane and had been killed by the police when he, strangely, returned it to the same airport from where he had taken it. Antonioni had passed the story on to his script collaborators as a possible thread in the narrative that would tie together different ideas that he had been developing during his stay in England. After the financial and critical success of Blow-Up a move to the US seemed logical, as, aside from London’s incredible cultural surge during that time, the heart of the cultural and political storms of the 1960’s was located in the USA.

Those were pivotal, violent and transformative years in American history as the country struggled to recover from the shocks that saw the assassination of Bobby Kennedy and Martin Luther King among other activists for a left or liberal agenda. There was the civil rights movement that had started in the mid-fifties, then the black-power movement that was partially a response to the backlash against the civil rights struggles. The anti-war movement that lasted throughout the sixties sought to end the colonialist war that the US was waging in Vietnam, and to engage in active resistance to conscription (“the Draft”). This was also the beginning of the Chicano movement, and a resurgence of what would come to be known as second wave feminism. Partly inspired by feminists the LGBT community began what would be called the gay rights movement. In short, the USA in 1969 was a battlefield with many fronts, that saw not only the inauguration of the conservative Republican Richard Nixon as president in January but also the first Woodstock Music festival that summer, a beautiful symbol of opposing ways to see the world, headed for a collision. Zabriskie Point is a film about that collision.

Throughout the late sixties Europeans and Latin American filmmakers confronted their contemporary difficulties head-on with prodigious artistic force, far surpassing the superficial glamour of Pop Art or the more traditional allegories of belles-lettres during the same period. Jean-Luc Godard’s One Plus One (1968), Marco Ferreri’s Dillinger is Dead (1969), Ingmar Bergman’s Shame (1968), Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Pigsty (1969), Liliana Cavani’s The Year of the Cannibals (1969) and Glauber Rocha’s Antonio das Mortes (1969) were all brilliant, in some cases highly eccentric, works that dissected and contextualized their contemporary realities with often spectacular visual force. Conversely there were very few American films then dealing with the current crises. From Oliver! to The Wrecking Crew (both 1969), and from Love Story to Airport (both 1970) - the highest grossing films in the US during those years - the works made tended to be fantasy art of the lowest order; even as kitsch they were unremarkable. There were some exceptions that stood out, such as Haskell Wexler’s Medium Cool (1969), but for the most part the extreme problems that the US was undergoing in this period were treated to the usual fantasies produced by the dream factory such as The Green Berets (1968), a utopian fantasy about American heroism in Vietnam, to Wild in the Streets (1968) a dystopian fantasy about a young, wealthy rock star who becomes president of the US and leads the country into a murderous tyranny. Antonioni’s work, although made by an Italian who never lived in the US for any extended period of time, is one of the few films that captured that time period in all of its incendiary contradictions, as if the wounds were out in the open. As is to be expected the exposed wounds were embarrassing and made audiences uneasy. It is fortunate for us that Antonioni, for reasons of his own, decided in 1969 to head into the heart of the battlefield that was the USA.

Zabriskie Point is the lowest point in the North American continent, a part of Death Valley, that is a baking landmass composed of salt deposits from an ancient lake that covers parts of California and Nevada. The film is about the interaction of that particular desert with two characters, a man and a woman played by Mark Frechette and Daria Halprin (significantly their real as well as their fictional names), who attempt in their own ways to adapt to their environment – the United States in the late 1960’s. The woman succeeds to a degree and the man fails and is killed. The film employs the conventions of the road movie starting in various locations in downtown Los Angeles, shifting to USC, a college campus during a demonstration, and then moving to Death Valley. The plot: Mark’s roommate participates in a student demonstration at his college against the Vietnam war and is arrested by police. Mark attempts to bail him out but is himself arrested, giving his name to the clerk in the police department as Karl Marx, that the official types out with an Americanized spelling: Carl Marx. Sometime later on the same campus, as things have reached boiling point, a policeman is shot and killed. Mark is seen with a gun and is hunted by the police as the presumed killer. He goes on the run to the vast South Bay area of Los Angeles, then a working class section of the city, and stops at the Hawthorne Airport where he steals a private plane. Daria is a temporary Girl Friday in one of the modern office buildings in downtown Los Angeles that houses the Sunny Dunes Corporation – a real estate firm that has invested in the outlying desert as the next spot for suburban migration. Mark flies to the desert and spots Daria driving to a mansion for a meeting with her boss. He lands his plane in the middle of the desert and the two meet and become a couple. He then paints his plane in psychedelic colors, flies back to the airport where he stole the plane, and is shot by waiting police. Daria goes to the meeting in the desert, but when she hears of Mark’s death on the car radio she decides to leave. Before going off alone she imagines the house and all of the objects in it blowing up which we see in slow motion.

The film was written by Sam Shepard, Franco Rossetti, Tonino Guerra, Clare Peploe and Antonioni. Sam Shepard, an American writer not well known in 1969, would become in the 1970’s one of the most famous and prolific playwrights of his generation, exploring the darker, violent and more eccentric aspect of the American psyche. Franco Rossetti is an Italian screenwriter who then specialized in Italian Westerns with titles such as Goodbye Texas. Whatever the plots, in his films people and rugged formidable landscapes were always the primary players. Clare Peploe specialized in romantic dramas and her most interesting work as a writer/director was probably The Triumph of Love, an adaptation of Pierre de Marivaux’s play. Tonino Guerra was a screenwriter who had a great feeling for uncertain or transitional emotional states that were informed by location. This would make him the ideal collaborator for Andrei Tarkovsky, Federico Fellini and Theo Angelopolous, but his longest relationship was with Antonioni, with whom he collaborated seven times. In terms of creating a narrative within the genre of the road movie this combination of talents was pushed by Antonioni to describe the present moment as a nexus of competing discourses and signs negotiating for space - the American battlefields of 1969.

It’s clear that in Zabriskie Point the thematic narrative strands and the formal visual architecture of the film are beginning to consciously unravel as the poetics are beginning to come loose from the narrative. This pressure on the narrative to italicize the genre element, or place it within quotation marks, was also being felt by other artists in the same period in their work. This is seen most clearly in Jean-Luc Godard’s Weekend (1967) that also shares with Antonioni’s film the road movie structure – that is subsequently pulled apart – and a moral critique that saturates both works in an aura of conscientious objection (a popular phrase of the period). In Zabriskie Point qualities that highlighted Antonioni’s aesthetics, such as paradox, ambiguity and contradiction, would be taken to new extremes in a manner not seen outside of avant-garde films as Antonioni experimented with narrative and editing within the context of the feature film. His style from L’Avventura onwards used a language of fragmentation and elision, of isolating gestures and looks, creating a camera consciousness that closed in on faces and hands, lingering on objects and spaces between people, and these qualities would also be pushed to the breaking point, but, always with the proviso that there were classical landscapes and close-ups to act as a counterpoint.

MACHINE AMERICA

The film was perceived upon its release to be an attack on capitalist America that was sympathetic to the far left in its program of confrontation with a surging corporate state – what Allen Ginsberg described so well as “Machine America.” Despite the brilliance of the images that are generally acknowledged as belonging to Antonioni’s best work, the narrative and the acting, particularly by the two leads, were often derided both when the work came out in 1970 and subsequently as unnatural, artificial and detrimental to the overall success of the film. Seymor Chatman in his fine book on Antonioni writes: “…the film is hard to read except as a portrayal of the American scene, as a defense of revolutionary youth and as an attack on a materialism that finds its ripest head in Southern California. Despite certain marvelous details there are many mistakes in Antonioni’s reconstruction of Sunbelt people and preoccupations.”1

For Chatman and for many critics of the film the problems begin at the beginning. While the credits are rolling we see what appears to be a realistic scene of young people planning a student demonstration against the Vietnam war led by Catherine Cleaver who was then a formidable organizer and public speaker well known in the radical press. The meeting constitutes a cross segment of the New Left, and is highly realistic in its use of dialog with student radicals planning a demonstration, the possible responses by the police and the best ways to preemptively manage the confrontation. White radicals mix with Black Panther Party members, students, professional revolutionaries, curious onlookers and organizers. This scene takes place in Oakland near the headquarters of the Black Panther Party, and was shot using the cinematic conventions that we associate with documentary. That is, a hand held camera and a long lens with a shallow depth of field that stylistically references cinéma vérité. Occasionally the sound is layered with noise/music while the diegetic talk becomes either silent or is pushed to the background and mixed through electronic filters, becoming barely audible. This noise/music is a sound collage that uses non-synced dialogue, electronic feedback and brief bursts of atonal music to create a dense overlay of sounds. The soundtrack disrupts or nullifies the documentary aspect creating a new space in which different orders of cinematic signs can co-exist within the same sequence. Antonioni’s opposition during the credits sets the stage for the film to come.

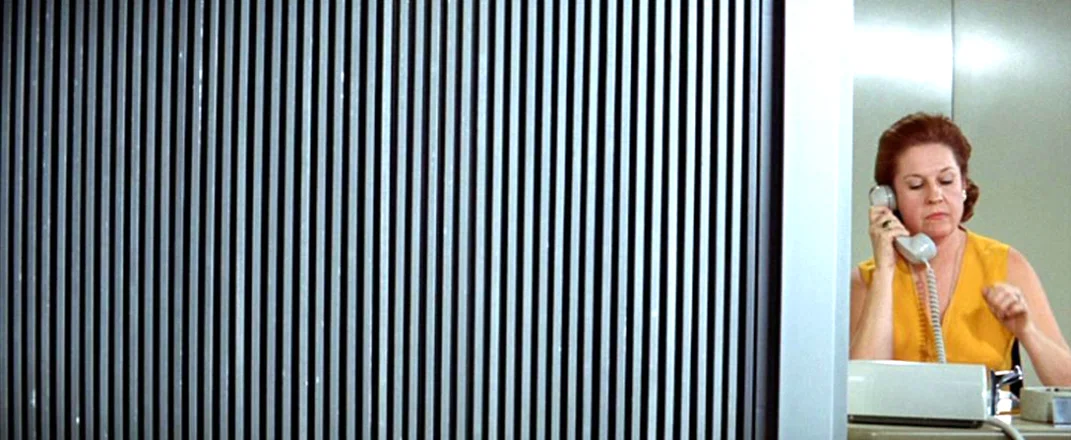

Zabriskie Point The aspect ratio pushed to extremes as the human element has been almost eliminated from the frame by the new dominant element: corporate architecture.

Catherine Cleaver during the credit sequence in Zabriskie Point

Zabriskie Point Advertising dominates the man made landscape of Los Angeles. The character is almost incidental to the space - he is merely passing through.

RADICAL AUTHENTICITY

While many critics mentioned that this prelude was beautifully shot it was also made clear by many who understood the various factions within the left that there was little contact, in real life, between the student movement and the Black Panther Party as seen in the film. The former was essentially a white phenomenon and restricted to the anti-war movement and was working, with perhaps more heart felt emotion than any kind of realistic agenda, toward a more European or Socialist model of society. The Black Panther Party was a revolutionary movement with a quasi Marxist agenda filtered through radical anti-slavery movements of the past and civil rights movements of the present (1969) and dedicated to the taking of political power, at least within their own communities, which they perceived to be under attack by the state. The Black Panther Party and what was then known as the New Left tended to distrust each other and in many cases were openly antagonistic and contemptuous. Was Antonioni oblivious to this chasm or did he consciously create this fiction – this meeting of blacks and whites - for some other purpose? And if so what might that be?

What the film shows is a war room in action and this is the critically important aspect of this scene. The United States was battling in various fronts in the late 1960’s. The most well known of these is obviously Vietnam, but there were several wars going on at home: There was the struggle of poor people and third world immigrants fighting for the available jobs and wealth; of women against the authority and power of an outmoded patriarchy; of working people trying to maintain their jobs in the face of corporate cutbacks and shifts away from an industrial economy; of blacks against white supremacists; and of the younger intellectual classes against the already established orders of power within academic institutions. The war that Zabriskie Point concentrated on was the war of the oligarchy, and the corporate classes that work under them, against the surging counterculture that were openly antagonistic, expressing their moral disgust in various ways through the art, music and writing of the period. In terms of cultural production this was a conflict between corporate art - that is advertising, official museum art, and commercial films on the one hand - against the works of the counter-culture by independent filmmakers, writers and artists on the other. Of course as in any war, there were those that played both sides of the field, hoping that they would land on their feet regardless of who won. The triumph in the USA of what we might call corporate, state art, entertainment, and spectacle, is one of the principal themes of the film as Antonioni was in the heart of it as it was happening. Yet another way to see this early scene is as a subtle criticism of the New Left that Antonioni accomplishes by emphasizing the schoolroom ambience, something that the participants themselves were probably oblivious to. It all serves to create a mix that was then derisively called Café Communism. Antonioni does not explicitly state it, but this subtext of lost youth has been planted. One might say that, like Godard with La Chinoise (1967), both filmmakers were sympathetic and critical at the same time, and their work reflected that ambivalence.

What Antonioni does with this war room scene is consolidate all of those conflicts into one. He lucidly brings all of these groups into one room, which is something that rarely happened in real life, to air their grievances as if they had been doing it for years because he is after a certain quality underlying their unity and their disagreements. We might call this quality radical authenticity. Put simply these protesters want to bring down powerful institutions that are at the service of the ruling classes, and they want to do this in order to create a more egalitarian and just society. The romantic aspect of this radicalism was clearly evident to Antonioni. This is unusual, as it typically takes a certain lapse of time for radicalism of any kind to become romantic or sexy, as happened for example with the Baader-Meinhof group in Germany who inspired filmmakers, artists and clothing designers once their radicalism was no longer a threat - that is once they were dead. The difference is that Antonioni was there in the present and gets both the romanticism and the disagreements within the New Left as they were happening.

ONLY THE BLOOD WAS CAKED

These ruptures within the various factions within the left during the 1970’s would only widen over time. The onslaught of repression that followed the election of Richard Nixon in 1968 came to a climax in 1970 at Kent State University, the same year the film was released, with the murder of four students by National Guardsmen and the wounding of nine others including one who suffered permanent paralysis. Those brutal murders and subsequent repression by the corporate state were for the New Left the beginning of the end, just as the murder of Fred Hampton, a leader of the Black Panther Party in 1969 by police, while he was sleeping, signaled the eventual exile of many of its leaders, and its marginalization within the population at large, as the mainstream media predictably followed the politics of the hard right dictated by the powerful elites in Washington and New York.

Shortly before he died Tom Hayden, a writer, leftist organizer and activist – and founder of Students for a Democratic Society - gave a speech at a conference in Washington D.C. titled “Vietnam: The Power of Protest.” Tom Hayden: “…there are very powerful forces in our country who stand for denial, not just climate denial, but generational denial, Vietnam denial. There are forces that stand for ethnic cleansing, but not just ethnic cleansing, but also for historic cleansing. And that is what has happened. It serves their purpose because they have no interest in the true history of a war in which they sent thousands to their deaths and, almost before the blood had dried, were moving up the national security ladder and showing up for television interviews to advertise what they called the next cakewalks. Only the blood was caked.” Those powerful forces standing for denial were present in the sixties and Zabriskie Point is an aesthetic attack on the war/consumer culture they created and handed to the population at large as a fait accompli – “democracy” notwithstanding. Hayden in the same speech also called his own generation – to which Mark and Daria belonged – the generation of “what-might-have-been.” There was a strong sense within the youth movement and the counterculture in the late sixties and seventies of having been shut down just as they were getting going, and that generation was never able to recover its collective soul. This is the feeling that is perfectly captured in Zabriskie Point as a subtext, as it is never explicitly stated, but it is all the more powerful for always being constantly just under the surface, for that is how it was experienced at the time.

La Chinoise 1967 Jean-Luc Godard The beautiful radical couple playing seriously with toys and Marxist politics.

Zabriskie Point The character in dialog with the space - a place not conducive to human interaction but made for cars and buses.

DIFFERENT CONTINENTS

Antonioni shoots the meeting with the fluid motions of a hand held 16mm camera but the format and grain tell us that it’s a large and heavy Panavision camera that is a piece of equipment impossible to carry, the hand-held aspect is a fiction. Antonioni’s cinematographer Alfio Contini used his large format camera in the manner of a hand held 16mm camera normally associated with documentary films, and at other times Super-8 film, a medium that is identified with home movies. He did this by brilliantly mimicking their conventions. For example, the shots of Los Angeles seen from the inside of Mark’s old truck beautifully reproduce the effects of the popular zoom feature in Super-8 cameras that compresses space by establishing large areas of the frame that are out of focus making the film jumpy and erratic, creating a sense of abstraction and dislocation. We hear the non-diegetic electronic noise/music while Mark is driving through the downtown LA warehouse and meatpacking district adding to the sense of disturbance and disarray. Antonioni’s documentary shots of the billboards and murals that clash with the power lines and the industrial environment beautifully show us a city obsessed with images and movement in the midst of a massive, shattering transformation.

To Brooke Hayward, an LA resident, in her interview/memoir of life in the city in that period, Los Angeles was in the process of “... transforming itself from being a small industry town to being a kind of battlefield.”2 In Zabriskie Point one sees that battlefield clearly laid out and it is, as to be expected, a dangerous, chaotic madhouse that people navigate at their own peril. Antonioni astutely contrasts the poor eastern part of downtown Los Angeles with the wealthy mid-town banking district. We hear the same non-diegetic electronic noise/music we heard in Mark’s truck in the luxury car driven by Lee Allen (Rod Taylor), the CEO of Sunny Dunes, as he drives around the financial district. Ironically these two sides of the economic spectrum are very close to each other geographically, but as in many cities that proximity is meaningless, as the financial and social barriers that separate them are enormous – Mark and Lee might as well be in different continents. The sound links these two characters that never meet in the film. Both men are in love with the same woman – Daria - and as genre dictates they both represent very different moral and emotional sensibilities, as well as economic and hierarchical standings, within the society.

In a series of striking shots we see glimpses of an older Los Angeles from Lee Allen’s modernist office with large windows overlooking the city. This office was located near Wilshire Boulevard in the downtown area and had a spectacular view of the city skyline. Antonioni went to great pains, and expense, to light the office with the same color temperature as the outside, creating the possibility of using deep focus to shoot Lee Allen at his desk and the skyline, both in sharp focus, establishing a dialog between actors and location. These extraordinary shots give the sensation that the interior space and the man made landscape outside go on forever morphing into one large electronically controlled space. Buildings from various time periods rise up like markers, most prominently a magnificent black and gold Art Deco tower on Flower St. Not surprisingly this landmark building was demolished shortly after the film was made, to make way for the new sleek skyscrapers that would come to dominate the city, and that were more in keeping with the international style of architecture favored by the surging corporate state. From the point-of-view of Mark, as he rides around on his truck the city seems to already be a collage that is in the process of being created and destroyed at the same time, with no time to reflect on the historical causes or the psychological effects.

GIRL FRIDAY

Daria works as a temporary girl Friday in a high rise that is the site of Sunny Dunes Corporation. Their lobby houses a computer the size of a small apartment surrounded by a glass walls that is a remarkable and beautiful display of wealth and power. As Daria walks through the space we see that it has a security guard sitting inside a circular desk containing a bank of television monitors that surround him. This is a video panopticon from which he can perform surveillance over the entire building. Because of the proximity to the computer we can’t help but feel that the machine is the permanent fixture in charge and the guard – or humans generally - are merely temporary employees, anonymous and easily replaced. In a comical exchange with the guard Daria explains that she has forgotten a book and needs to go back inside. The security person asks her suspiciously: “Book - what kind of book?” Lee is obviously attracted to Daria and wants an excuse to help. The real exchange in this scene is not between Lee and Daria, since the narrative convention of the boss and the temporary worker that he lusts after is well known and we don’t need details.

Antonioni’s real interest here is between Daria’s integrity, innocence, the level of comfort in her own skin and the computer, the bank of monitors and the building itself. She is in dialogue with this strange, antiseptic, corporate space – a space of supermodernity - what the sociologist Marc Augé would later call a “non-place.” Marc Augé explains the difference between classical modernity and supermodernity: “What is seen by the spectator of modernity is the interweaving of old and new. Supermodernity, though, makes the old (history) into a specific spectacle, as it does with all exoticism and all local particularity. History and exoticism play the same role in it as the ‘quotations’ in a written text: a status superbly expressed in travel agency catalogues. In the non-places of supermodernity, there is always a specific position for curiosities…but they are not integrated with anything; they simply bear witness during a journey, to the coexistence of distinctive individualities, perceived as equivalent and unconnected. …The non-place is the opposite of utopia: it exists, and it does not contain any organic society.”3 Augé’s metaphor of the travel agency catalogue is apt for such brochures itemize presumably desirable spaces but at the same time empty them out so they become petrified museum images, full of deracinated ghosts - a flat parallel world of "tourism." Antonioni wants to capture what happens when a real person inhabits such a space, and the effect is, as one would expect, somewhat comical. Daria was a professional dancer before joining Antonioni’s film, and was very much at ease in her own skin, in the way she carried herself and walked through a space. This contrast between the organically healthy, the connected, in the presence of Daria, and the manufactured disconnected space of supermodernity – a space that was then new but that we occupy today as a matter of course - is what comes to the foreground . Unlike the earlier short film Screen Test, Antonioni here beautifully articulates the silent communication that is happening between the female lead and the architecture and he makes it work for him. This visual dialogue is funny, poignant, disturbing and tragic.

Zabriskie Point Mimicking the zoom effects of the Super-8 camera.

Zabriskie Point Interior and exterior in perfect focus create a dialogue.

Zabriskie Point Interior and exterior follow the same perspective lines creating a sense of a total man made landscape that goes on forever.

TELEFISSION

In Zabriskie Point there is a magnificent film-within-a-film - a short television advertising for Sunny Dunes Estates. This promotional film is inter-cut with a group of corporate men and women sitting around a large table carefully measuring the effectiveness of their new commercial. This film has voice-overs done by professional male and female voices common to advertising that is enthusiastic, positive, and without inflection or depth. When the male voice gives the number to call for more information the female voice asks for the number again in artificially perky tones that are comically unreal. The voice-overs explain that Death Valley is the place where one can retire to hunt, play golf, bar-be-cue some burgers, water one’s garden and lounge poolside with no urban cares or worries. The film overtly mimics the commercial style of traditional or Hollywood cinema, reveling in parody, which is unusual for Antonioni as he rarely played this card previously. We saw glimpses in some of his short films, such as Lies of Love, where he lampooned the stylistic devices of melodrama that he himself had employed earlier. This element of mockery is similar to other films from the same period: Pier Paolo Pasolini's brilliant farce as he took on the biblical epic in La Ricotta (1962), Joseph Losey's send-up of the macho spy film in Modesty Blaise (1966), Nicolas Roeg’s and Donald Cammell’s deconstruction of the gangster film in Performance (1970), Don Levy’s satirical deconstruction of consumer culture’s blind dominance in Herostratus (1967),Theodore J. Flicker’s ingenious pastiche of Hitchcock in The President’s Analyst (1967) and Federico Fellini’s revolutionary reconstruction of the documentary in Roma (1972).

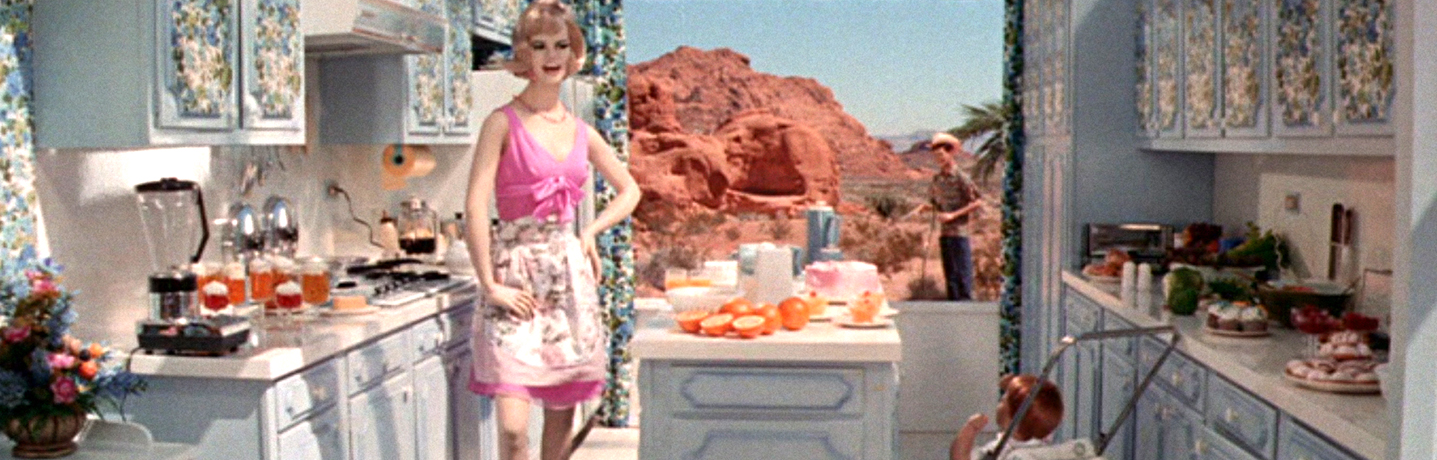

Visually the commercial sequence has a young couple, represented by male and female Barbie sized dolls in an idealized modern home setting. They are doppelgangers of Mark and Daria but now seen as a happy, well-adjusted couple, conforming comfortably in the suburbs. The doll sized modernist house in the film within a film is shot from the appropriate points of view to give the impression of a clean, expansive, state-of-the-art interior space. Clearly the architectural planners, engineers and developers are on the fringes of civilization – they are pioneers – and they bring the most advanced component of their education and training with them: rationalist modernism. What the developers casually ignore is that it’s called Death Valley for a reason. This is after all where the American Air Force, the most advanced war machine on earth, test experimental aircraft and rockets. The point being that if something goes wrong the casualties are minimal. The sequence captures the encroachment of suburban Los Angeles into the desert and has a strongly ironic component that is brought dramatically to the foreground, but unlike academic exercises that attempt this kind of irony – that we see regularly in avant-garde fine art practice - Antonioni never lets the rhetorical or pedantic aspect take control.

He mimics the framing and cutting of commercials to great effect, deconstructing the form and undermining their content. Antonioni invents brilliant points from which to shoot the model house, parodying the classic “well composed” shots that are the backbone of commercial cinema. He captures the surfaces of plastic and glass, playing them off against the faux natural surfaces of sand, blue skies and desert plants – all of course fake. The color palette is tan, brown yellow and orange that serves to highlight the artificiality of the Sunny Dunes homes. The female doll cooks (of course) in a modernist kitchen overlooking the desert while the male doll waters his garden with a hose (of course) with plentiful water available for all. This is the water problem depicted brilliantly in Chinatown (1974) turned into a farce by corporate advertising. The kitchen is enclosed in glass panels that separate “nature” from the plastic interior space thereby suggesting that the exterior – Death Valley – is merely a picturesque, natural wonder, literally framed – and thereby presumably contained - by modernist architecture. In bourgeois terms, nature becomes a view offering us the picturesque. Roland Barthes, writing about the Blue Guide, states that the bourgeois promotion of mountains and alpine myths are associated with Protestant morality, which “... as always functioned as a bastardized mixture of nature worship and puritanism (regeneration by pure air, ethical convictions in the presence of mountain peaks, climbing as a civic function, etc.).”3 In effect what Barthes does for the Blue Guide Antonioni does for American television advertising and the exploitation and commodification of everyday life.

This criticism of commercialism, using the visual vocabulary of consumer culture itself links Zabriskie Point to the Pop Art of the same period. In James Rosenquist’s luminous painting F-111 (1964) he combines seemingly random images, in the style of Robert Rauschenberg, but in fact the images, taken from popular magazines of the time, were carefully selected to create a narrative in which a massive collision between war, media, technology and consumer culture ends in nuclear fallout. Rosenquist’s own description of his painting could serve very well to describe Antonioni’s film: “In F-111 I used a fighter bomber flying through the flax of consumer society to question the collusion between the Vietnam death machine, consumerism, the media, and advertising.”5

The palette of warm tones in the promotional film is balanced by the shots of the corporate office space of cooler grays and blues. The business people sit very quietly around a conference table smoking with a funereal seriousness while watching the commercial. It is as if someone had told them that only half the people in the room are going to get out alive and they must now decide which half. In effect this is more or less the situation. The stakes are very high and the fear under the surface is palpable. The Sunny Dunes commercial has a fake bird being held aloft by wires that the doll-sized man shoots with a toy gun. The sequence both mimics the realistic violence that ends the film with the shooting of Mark and parallels the absurd frozen chicken that later in the film floats through space. Antonioni makes the connection between the Sunny Dunes aesthetic, as stated in their own promotional film, and a pathological death drive, in effect hoisting the Sunny Dunes executives on their own petard. The advertising short describes a fantasy that is being sold literally by the square foot. The overall effect is grotesquely comical and far-sighted, a stunning accomplishment for a scene that lasts one minute and twenty seconds. It is one of the most brilliant set pieces that Antonioni ever accomplished and remains to this day one of the most devastating criticisms of the corporate world and its relation to propaganda, advertising, consumerism and media control. In subsequent years that system of corporate values, at least in the USA, would be internalized by the population at large and adapted as the norm primarily through television, or perhaps more accurately via what Jean Baudrillard called “telefission.”

Zabriskie Point The traditional point from which to shoot - exactly as they teach it in film school - lampooned by Antonioni using dolls and toy furniture to satirize the real estate promotion of "the good life" available in Death Valley.

Zabriskie Point The landscape outside becomes framed and presumably controlled by modernist space.

Zabriskie Point The car, from the post-war era of black and white cinema, and the road barrier on the right form a triangle, and at the center is Daria.

TENNESSEE WALTZ

On Daria’s road trip she comes upon a bar in the middle of the desert in which old timers, including the middleweight champion of the world from a bygone era, is having a beer. She casually goes outside where some boys are playing by themselves. They all gravitate toward a stage that stands baking in the desert along with a broken grand piano that a boy plays by strumming the gutted strings creating an atonal sonata that is appropriately disturbing and otherworldly. The boys are uneasily balanced between a feral clan and a rural country gang, somewhat bored and quite obviously with no direction home. They are perhaps the sons from the commune that Daria has been asking about which would explain their openly asking her if they “can have a piece of ass.” Daria asks them, with some trepidation, if they would know what to do with it. At that point the boys begin to push and shove and Daria makes a run for it. As she makes her way back on the road the camera, instead of following her escape as would happen in a conventional film, slowly and lovingly pans forward to the window of the bar as we see the old champ sipping his beer to the sound of Patti Page’s classic song “Tennessee Waltz,” that evokes a bygone cavalier romanticism that seems as anachronistic in this setting as the ruins of a classical piano in the desert. We remain respectfully outside observing through glass, what looks like a tableau from the early part of the century, perhaps belonging to Edward Hopper if the American master painter had ever traveled west. It’s a brief and beautiful farewell to another era, but one that American directors themselves were too busy to express in the excitement of the time. Antonioni just managed to pull it off using veteran actors from an older, more creative and inventive Hollywood, that was soon to be replaced by a more efficient corporate model along the lines of the commercial for Sunny Dunes.

Daria has been summoned to the desert by her boss Lee Allen who is attempting to sell lots to developers and investors in a modernist mansion in the desert that resembles the ideal Sunny Dunes home but on a massive scale, isolated on a pedestal of rock, surrounded by a vast and spectacular landscape. As one would expect Lee is seeking to turn the planned sales event in the desert into a vacation weekend with Daria, whom he hopes will become his mistress, as he finalizes the deal with the developers. She drives to Death Valley in a vintage car from the noir-era of American film. Intrigued from the air, as he escapes from his problems in LA, Mark literally swoops down on her and after landing, they become, for a brief time, a couple.

ACTING THE PART

The use of non-professional actors in the lead roles was a decision that bears re-assessment as not enough attention has been paid to this important part of the film’s accomplishment. Daria and Mark’s dialogue throughout is forced and self-conscious, often delivered in a hesitant, uncertain monotone. The effect is to make us conscious of watching acting but not in the Brechtian sense. Rather, the film seems to document uneasiness, uncertainty, and a willful integrity that refuses to act. The leads seem to be at odds with anything artificial including cinematic conventions of acting themselves. It is in this refusal to act the part that the actors in Zabriskie Point collide with narrative expectations. They are a romantic couple in a road movie and the genre was already well trodden by 1969 with conventions and expectations built into it.

The language of conventional narrative cinema demands a particular aesthetic of acting: A theatrical tendency to gesticulate for effect, to project outward, to render certain thoughts and feelings crassly legible, to inflect and thereby dramatize, to clarify relationships and situations and guide the audience to a “correct” reading of the film. For Mark and Daria it would seem any nod to those established conventions would call into question their authenticity and undermine their actual incommunicability, and their discomfort with those rules. The actors are in their way speaking truth to power in the most candid manner possible, in front of a camera that picks up every nuance of action or lack of it and every sound and silence. Mark’s inertness is very close to the sleepwalking saints in Robert Bresson’s films, where inflection is kept to a whisper, but here his refusal to have a clearly defined persona, or to put it in entertainment terms, his refusal to do shtick, is his principal characteristic in the film. In short Mark is about this refusal to go along with the program and he takes that refusal to its logical conclusion: suicide. Daria’s acting is more complex, more conventional and more pragmatic. While she shares Mark’s uneasiness she is not intent on exposing it brazenly to the camera and makes an effort within the conventional norms of professional film acting. This puts her in a no-man’s land between Mark’s radical resistance and the prevailing norms of the Hollywood style, personified by Daria’s boorish boss Lee Allen (Rod Taylor). Antonioni carefully orchestrates the acting styles as beautifully as Jean Renoir, who was a master of pitting various acting techniques within the same film, often to characterize differences in class – and that aspect of class differences is crucial to Zabriskie Point as well.

Antonioni does not dismiss professional Hollywood acting standards but uses the aggressive charm and faux naturalistic expressiveness that is the backbone of the Hollywood style in the characters of the business people and the police. Significantly the professional actors don’t use their real names in the film, as do Mark and Daria. The acting in the film comes to the foreground in a way that is too direct, even confrontational, for a conventional narrative film, but far too subtle for a satiric avant-garde gesture in the manner of Godard’s humorous and horrifying caricatures of bourgeois types in Weekend. Mark and Daria in effect refuse to act the part while acting the part, and this uneasy duality becomes one of the strongest thematic elements in the film. The narrative action in conflict with the mise-en-scène sets in relief this central dilemma and Antonioni treats it like a dialectical construction that is central to the film. How does this dialectic actually work?

In Antonioni’s earlier film Attempted Suicide (1953) he carefully navigates difficult terrain as young people re-enact attempted suicide attempts and, in effect, play themselves while “acting” out a traumatic event from their lives in the actual location that it happened – an attempted suicide that they then try to explain in voice over. In both Zabriskie Point and Attempted Suicide Antonioni shifts, with great subtlety, from representation to presentation. The camera documents the attempt at a performance, rather than a performance, and that is the key. As Andre Bazin said of Moliere’s play Imaginary Malady, a performance on film would probably not be particularly interesting or rewarding, but to see a film of Moliere and his actors in rehearsals learning their parts, even awkwardly, would be an amazing film. Effectively the ontology of physical reality always trumps narrative conventions and, regardless of the circumstances, eventually supersedes them. Sooner or later all films eventually become documentaries of their own production, of their performances, and if they are shot in the world at large, of their period and place in history. This method brings Antonioni close to Andy Warhol's film aesthetic during the same period in which he sought to find that place in between acting and not acting, between fiction and non-fiction, in films such as Chelsea Girls (1966).

As evidence of the documentary aspect of fictional films, we can see that even mediocre films can become fascinating for the realistic elements, that were perhaps coincidental to the film, but that have come forward over time as the plot, and the theatrics, recedes and fades into the background. Two examples: We now watch the films of Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers to see them dance, not to see how their relationship will work out – invariably it does. We now see The Temptress (1926), a typical melodrama of the period, not for the plot but to see Greta Garbo’s face react to subtle emotional nuances; to see flappers from the jazz age – who happen to be actors or extras – move and dance in a party in ways peculiar to their time; to see streets with traffic and pedestrians from 1926. Sooner or later ontology oversteps and eventually supersedes narrative - and the latter becomes a ground or surface on which the former may begin its long reign.

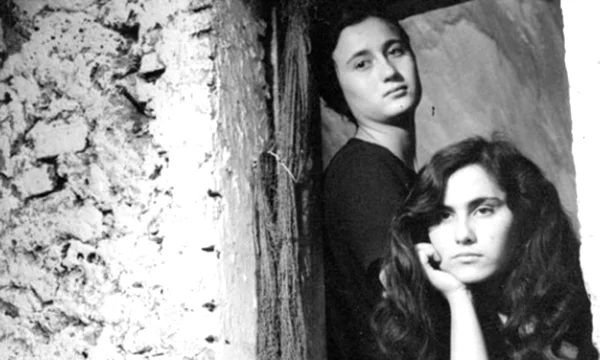

Antonioni’s formative films had been made in the context of neorealism where the use of non-professional actors, in such films as Luchino Visconti’s La Terra Trema (1948) or Roberto Rossellini’s Stromboli (1950), was a common practice that was by 1950 already an established convention – one that the originators of neorealism themselves moved away from and reformulated to the new situation of the 1950’s and 1960’s. American and British critics responded generally favorably to the wildly different acting styles, since non-actors and professionals often shared scenes, as a sign of authenticity that sought to incorporate documentary elements – and thereby revitalize - traditional fiction genres that were becoming staid and clichéd. When Antonioni pursued this same line of reasoning, but with the upper-middle classes of Milan in La Notte, or when Pasolini did something similar with contemporary Romans in Mama Roma (1962), many critics balked at the shift as they didn’t understand how a moral critique could be applied in the same manner. When Rossellini or Visconti criticized working conditions for poor people in the rural parts of Italy it was relatively easy to reach a positive consensus, but when the drama and the criticism happened within the middle and upper classes of Milan or Rome critics inevitably became defensive.

Antonioni encountered the same problem with critics in the USA. Zabriskie Point’s two leads destabilize the narrative by incorporating their real lives and the baggage that they carried with them as young Americans, just as the fishermen in Visconti’s La Terra Trema incorporated the facial gestures, body language and colloquialisms of people who had spent their lives working in a village in Italy. Mark is a working class youth who hates theatricality, display and pomposity with a passion and that comes through very well; Daria is a middle class woman who sympathizes with Mark but is more open to traditional conventions and how she might fit into them, and that comes through as well. Antonioni was consciously bringing the aesthetic of neorealism to the present and testing it out in American waters by applying its moral values and ethical criticism in the USA. That critics and audiences felt uneasy was, under the circumstances, predictable. Aside from re-inventing neorealism – an accomplishment in itself – Antonioni along with his two non-actors is contrasting a certain kind of radical authenticity, in this case radical not so much because of what they do but because of what they refuse to do, with the artificiality and shallowness of American corporate culture exemplified by Sunny Dunes’ executives’ polished “professionalism.” Antonioni was not alone in re-inventing neorealism as in this same time period similar radical ideas or how to present “reality,” as perceived and constructed, individually and collectively, were being reformulated by the originators of the movement - most forcefully with Roberto Rossellini's The Age of the Medici (1972-1973) and Vittorio de Sica's The Garden of the Finzi-Continis (1970).

Zabriskie Point The postcard view where nature is a decorative element.

Zabriskie Point

NO WORDS

If Mark and Daria have difficulties with language one area where they can communicate effectively and clearly is in their physical contact with each other and with the landscape around them. Antonioni’s strong suit was always his ability to connect characters with landscapes and to explore the space between them. It is no accident that words get in the way. Mark paints “No Words” on the side of his stolen plane. Antonioni himself expressed doubts: “Someone once said that words, more than anything else, serve to hide our thoughts.”6 Antonioni is quoting, consciously or not, Voltaire who expressed the same idea: “People only use words to hide their thoughts and use thoughts only to justify the wrong they’ve done.”7 The two actors’ relation to the landscape is a healthy one of respect, admiration and play. They don’t fuck but rather make love in the desert, an important distinction that implies an element of play and childlike fun.

Antonioni depicts the lovemaking in slow close-up pans of their bodies in the sand set to the music of Jerry Garcia’s improvisations on guitar. Garcia’s music was associated with a meandering psychedelia free of the rationalist impulses found in traditional western music. Its closest antecedents are perhaps middle-eastern music and medieval drones. Garcia makes the perfect soundscape for the transition from Daria and Mark’s lovemaking to the orgy of young people in the desert that follows. That lovemaking, which seems to spring from Daria and Marks’ coupling, is not really lovemaking in the traditional sense but a highly stylized representation of it enacted by professional dancers who were members of Joe Chaikin’s Open Theater. This was an avant-garde group that stressed improvisation and organic movements that explored political, artistic and social issues tied very much to the contemporary scene. They mime a ballet of males and females playing with each other, exploring each other, mimicking the play of children but with adult bodies and an adult sexuality. The two are not separate, as in the puritan model, wherein one leaves behind the creative play of childhood to assume adult sexuality, responsibilities and ambitions, but they are integrated into an organic whole that is expressed in pantomime and dance.

The Open Theater group were carefully rehearsed by Antonioni who showed them the physical motions he wanted and the dancers improvised on these movements. His original intention was to have a cast of thousands in the desert but, due to financial restraints, could only come with the dozen that make up the troop and some extras that were hired to mimic the movements of the professional dancers. In some respects this smaller group worked in his favor as a group of thousands would have been somewhat anonymous and surreal while the actors he ends up with are both professional enough to mime this adult play effectively and their relatively small number allow us to see details that would have gotten lost in the crowd.

The intertwining bodies catch the sparkling desert sand on their bodies, faces and long hair creating sculptural tableaus that are reminiscent of European friezes but whose gestures and expressions are far from the heroic and unnatural poses of a bygone classicism. On the contrary the gestures encased in the “sand sculptures” in Zabriskie Point depict everyday, transitory, mortal pleasures and nuanced movements that are often comical suggesting physical intimacy as a form of communication and play. While this might sound like plain common sense the idea is revolutionary as it proposes that – as a counter to American puritanism and the war/consumer society that it has created – an orgy in nature is man’s natural state.

F-111 (Fragment) James Rosenquist

Zabriskie Point The orgy in the desert.

La Terra Trema Luchino Visconti Actors and non-actors share the same stage creating a sense of intimacy and authenticity.

A PAGAN RITE

Something else that this orgy suggests is made clear by Antonioni’s brilliant use of color and texture. The sand in Zabriskie Point and the flesh and clothing of the couples seem to interpenetrate in a manner that implies that human beings are a part of the earth in the literal sense, like minerals or plant life, and that we are connected to the planet in profoundly intimate ways that we have either lost touch with or perhaps never clearly understood. This orgy is clearly a pagan rite of the pre-Christian era but filtered through a benign hippie mindset. The communal ethos that is given a voice through The Open Theater group allows us to see with greater clarity the clear opposition between the orgy, and the Sunny Dunes aesthetic, announced with guns blazing (literally), in their promotional film. The orgy episode in effect has a similar function to the paradise sequence from Red Desert in that it allows us to catch a glimpse of the world – a utopia - that the characters might want to make or might have made under different circumstances but one that by definition will never be. Both utopian sequences suggest a pantheism in which everything is holistically connected. Antonioni ends the orgy in the desert with a slow pan of the sand sculpted in such a way that we see the imprint of human bodies making love that were once there. Nature trumps philosophies in Antonioni’s world regardless of how benign or insufferably self-serving. In that sense both the Sunny Dunes mansion in the desert that is blown-up, and the sex between Mark and Daria that creates an orgy - the two sides of the argument that are voiced throughout the film - are merely very small and very temporary marks in a desert that will far outlive the traces that humans leave on it.

A Pervert's Guide to Ideology Slavoj Žižek 2013 The philosopher in the desert.

Zabriskie Point The beautiful modernist cage.

ZIZEK'S COKE

The orgy scene explicitly accomplishes something else that is extremely important, it suggests that a sexual communion in nature - however that may manifest itself - is an ideal that mankind should strive to achieve because it is superior to the war/consumer culture created by the American corporate state. Antonioni lays it out very clearly – sex equals joy and war/consumerism equals death – that part is not complicated or ambiguous. For the philosopher Slavoj Zizek this is a main point of contention and his critique of Zabriskie Point is worth exploring to better understand Antonioni’s intentions. In Zizek’s wonderful film A Pervert’s Guide to Ideology (2013) we see the Slovenian philosopher in the site of the orgy in Zabriskie Point discussing the film while, improbably, drinking a Coke. His first point of contention is that the two leads are very beautiful and their exquisite close-ups could easily be an advertisement for soap. While this statement is clearly true one could say the same of virtually any image since advertising can cannibalize anything – it is the capitalist tool par-excellence. It is always, like capitalism itself, in a state of crisis and ecstasy, entrenchment and re-invention. For example, a shot from Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin, of handsome young sailors, can be used to sell men’s cologne. But this fact does not invalidate Eisenstein’s film, it merely illustrates that anything can be turned into merchandise, something that we surely already knew. Appropriation is a two-way street that flows in two directions, not one. Of course this new critical work – such as Antonioni’s film - can then be taken and reconfigured to sell another product. Any work of art can become raw material for new work that cannibalizes it and uses it to its own ends. Zizek fails to recognize that appropriation in itself does not transcend or invalidate the force of the original, regardless of the success of its ironic consummation - a similar mistake was made by many conceptual artists in the 1980’s such as Sherry Levine. A work that appropriates another draws a certain power from the original and then becomes a footnote to it, as the life span of pastiche, appropriation, parody or advertising, that draws from an original work for its power, is usually, thankfully, short.

Zizek’s second critique of Antonioni’s film is far more nuanced and profound. For Zizek any idealized social construction, be it Christianity, Stalinism or Capitalism are merely a set of illusions with an agenda. These systems perpetuate their ideologies by concealing them in works of popular culture and art that act as traps to ensnare viewers or consumers. All of these ideological constructions are referred to as “the other” – along Lacanian lines – and dismissed as a fantasy that conceals the ugly truth: we are alone. There are only individuals who are, each in their own way, struggling to get by and survive. While there is great truth in this statement it is also strangely similar to Margaret Thatcher’s famous comment that there is no such thing as society. What she meant by that is that society was an abstract concept that bore little or no relation to human beings as such – that is to individuals – therefore it could be eliminated in rhetoric as fundamentally unreal. For Thatcher works that referred to society, such as Mike Leigh’s Mean Time (1984), that deals with Thatcher’s England and its catastrophic effects on the working class people of London are simply not real. In Zizek’s world Antonioni’s orgy is an other, a social utopian fantasy of communion and free sex to hide the ugly truth that we are alone. Is Antonioni’s orgy an illusion? Is Zizek right and this hippie dream is yet another kind of soap advertising, with two pretty people seducing us to buy their product, different in content, but similarly predicated on fantasy?

In A Pervert’s Guide to the Cinema we see Zizek, quite alone except for the crew shooting him in one of the spectacular mountain peaks in Zabriskie Point, enjoying his Coke in the American desert. But Zizek knows full well that, by his own rules of ideological perversion, a can of Coke is never a can of Coke. The drink is America and the free market - it is neo-liberalism in a can. Zizek, with great wit, refutes Antonioni’s film by consuming the very kind of capitalist product that is blown up in the film, as if saying: “You thought you blew it up but it’s still here, you didn’t blow up anything, you didn't do anything real, it was all smoke and mirrors. The game’s up Michelangelo – I’m calling your bluff!” He is essentially criticizing Antonioni for having bad faith and for turning the revolutionary Marxist ideas of the sixties, exemplified by the writings of Theodore Adorno and Herbert Marcuse, into a simplistic romantic orgy that can be used to sell anything.

There is a beautiful dialectic at work in Antonioni’s film that refutes Zizec’s argument. The orgy in Zabriskie Point is preceded by Daria and Mark’s lovemaking so the entry point to this communion – this utopia - is sexual passion. For Antonioni we are not alone, but our communion with fellow travelers is an imaginative, or creative act, that is sexual whether we are aware of it or not. By having the orgy occur outside of the conventional road movie narrative, it intimately links it to the blow-up sequence later that also exists in a parallel world to the film’s narrative structure. The two scenes, of creation and destruction, are pagan rituals enacted in contemporary costume. In the orgy, somehow through lovemaking, time periods collapse, and the dead return to commune with the living and share in a delicate unspoken dialogue.

This is the heart of the film: Antonioni is able to evoke the present (The Vietnam war, the explosion of war/consumer culture, the student rebellion, the counterculture), the past (the downtown LA Art Deco buildings, the heavyweight champ from another era), and the pre-historic past (Zabriskie Point is the bed of an ancient lake) and this aspect is crucial if the film is to work, as those layers are a palimpsest that permeate the totality of the film. Zabriskie Point the place exists both within and without history, but to travel to Zabriskie Point the film requires an imaginative leap of faith into the poetics of the work. Once that leap is made history then exists as a living, organic, malleable thing - it exists within the far larger context of Nature - that envelops it and will ultimately absorb it. The present tense becomes alive and porous, flowing through people, and not a text, and most certainly not a philosophical tract. This is precisely where a philosopher, hopelessly tied to the absurd concepts of Hegelian historical narrative, such as Zizek, cannot travel, since for him it is not real.

Zabriskie Point The traditional postcard view is blown-up.

INVISIBLE WOMEN

Mark returns to Los Angeles with his stolen plane now painted with various slogans of the time including “No Words.” Antonioni contrasts Mark’s psychedelic artwork on the side of the plane to the conventional hard-edged graphics seen throughout the film in corporate spaces to great effect. He films the line of police, waiting for Mark at the airport, wearing protective gear in the manner of Goya’s executioner’s, that is, as anonymous agents of the state doing their job. Immediately after landing, without any attempt to capture him, he is shot dead. Daria returns to the modernist mansion where the executives from Sunny Dunes are trying, without much success, to finish a deal with investors while their women lounge poolside and chat. She has heard of Mark’s death on the car radio and momentarily stops by a decorative waterfall, the ultimate desert luxury, and cries. Antonioni’s contempt for this group of vacationing business people is brought home by having the only woman to acknowledge Daria’s presence be the American Indian maid who is cleaning the bedrooms. They are in a sense both invisible women. Daria then goes into a glass box that serves as a modernist stairwell and looks out very much like a caged animal, an image that links her to previous Antonioni heroines such as Monica Vitti in another modernist cage in L’Eclisse. This re-states one of Antonioni’s principal themes: that modernism, which was to have liberated mankind from the heavy ornamentation, patriarchy and repression of the previous century, is simply another kind of trap.

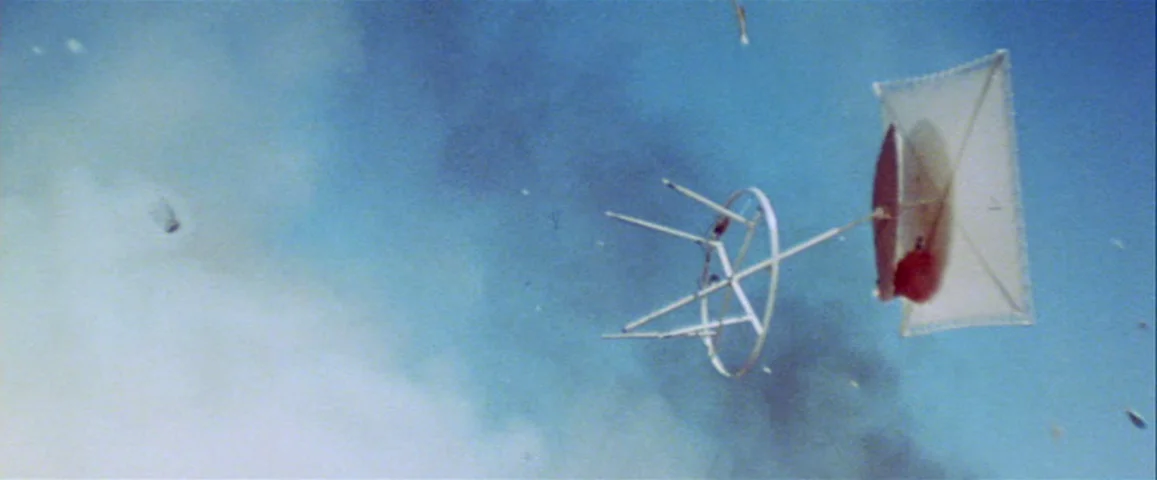

On the way back to her car Daria turns to look at the desert mansion in a close-up. We then see a reverse shot of the mansion as it explodes into a fireball turning into a sequence of shots from various angles using a telephoto lens. Ironically these shots were filmed from conventionally picturesque points that would be more appropriate for a postcard, lending the explosions a greater sense of unreality. In a literal and figurative sense, the “postcard view,” is blown up. Antonioni used seventeen cameras of various focal lengths to give the impression that the scale model of the house – built on site – was the real thing. After a moment the diegetic sounds of the explosions gives way to the music of Pink Floyd as we see the fireball from different angles and film speeds. The reverse shot of Daria’s face looking pleased and at peace at the end of the six-minute sequence makes it clear that it is some form of fantasy. But the mansion explodes not simply as the wish fulfillment of Daria but of everyone in the film including the developers themselves, at least subconsciously. The exploding modernist house resembles the ideal home in the Sunny Dunes advertising film seen earlier and this sequence is, in some sense, an inversion of that commercial film. This is made clear by having various shots repeat, such as the floating duck in the Sunny Dunes advertising short returning as a frozen chicken in the blow-up sequence. There are other parallels: The modernist furniture, the fancy refrigerator, the patio furniture that all make their appearance in the advertising film and are then blown up in slow motion at the end. This brilliant sequence is the most extraordinary in Antonioni’s body of work taking from Eisenstein, and his ideas of a “collision” of independent images to create metaphors, but advancing that formalist approach into new areas of possibility - but Antonioni establishes his film along its own path of ethical abhorrence and intellectual despair that would have been foreign to Eisenstein’s work.

The slow motion sequence has objects floating dreamily through space to the music of Pink Floyd in a manner that suggests Kubrick’s utopian waltz between a spaceship and an orbiting station in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) set to the music of Strauss, but now made absurd by having frozen food and patio furniture shot out from the force of an explosion. Strauss’ upper class dance music is now replaced by Pink Floyd’s democratic, drug induced dreaminess. It is impossible to see this footage now without thinking about terrorism and the implications of those explosions in human terms. What Antonioni does is turn them into an absurd ballet of flying meat. It is both painfully horrific and playfully absurd and it is meant to be. The most iconic shot in this sequence is perhaps the floating bag of Wonder Bread, one of the great shots in Antonioni’s body of work. The detonated television has a man’s face, the proverbial “talking head” exploding in slow motion. In effect Antonioni destroys not simply the apparatus but the content and the nonstop flow of propaganda, information and sales pitches. When the film was first released this shot was often met with laughter and applause from the audience. The exploding books, in which a modernist bookcase holding what looks like thousands of books explodes in slow motion, brings the “No Words” theme to its logical finale. The shot is not so much anti-intellectual as anti-collection – suggesting that the acquisition of books as trophies is not much different from any other form of consumerism.

The explosions in Zabriskie Point are the bombs everyone had been waiting for since the beginning of the cold war. Antonioni seems to have intuited the need in the population at large to see explosions in a psychedelic context. Characteristically he also finds beauty in the explosions – a catastrophe in slow motion that occurs amidst a vertigo of real estate speculation, overreach, and environmental delusion. The single explosion is repeated, like a musical motif, and seems finally liberated to express the full intensity of an imminent cataclysm that had been ticking for a decade. It finally carries out that threat, depicting the annihilation of the symbolic order of things. It is as if the counterculture overstepped all apprehensions and obstacles, and surmounted the powerful forces against them – and then through sheer moral repugnance vomited everything it had been forced fed, to compel the reality of war/consumer culture to rise above the veneer of appearances and state its true purpose. Like the great abstract expressionist paintings of a previous generation it offered its own numbness and disgust as a direct challenge to established order – an order that is overfull of meanings, abstractions, rationales, theories, and saturated with concepts ad nauseam. This rage, that is repeated like a visual mantra set to music, is the most ardently anti-classical gesture in Antonioni’s body of work, but not anti-humanist. Significantly Daria does not imagine any of the people in the mansion blowing up, only objects.

Zabriskie Point

Zabriskie Point

Zabriskie Point

PSYCHEDELIC CALCULUS

For Diedrich Diederichsen Zabriskie Point’s psychedelics are its primary reason for being: “Perhaps there is a case to be made, then, that Zabriskie Point can be RE-considered an exemplary instance of the dynamic contradictions inherent in the psychedelic vision – and that Daria’s experience is thus an embedded allusion to Antonioni’s overarching one, a mise-en-abyme fully in accordance with the laws that govern the psychedelic calculus of images. This would be (in the proper sense of the word) “obscene” nature of the psychedelic vision, as the vision has no frame, and no stage of representation, and within this mise-en-abyme is perhaps where Antonioni’s film allegorically turns on itself in all its suspect materiality, as celluloid that will ultimately itself be burnt through by Daria’s vision.” For Mr. Diederichsen the film itself should burn after the explosions so the work would not so much reach a conclusion as flame out and disintegrate into darkness. But this was already the ending to Two Lane Blacktop (1971) a coruscating film about contemporary America made by Monte Hellman and Rudy Wurlitzer. Interestingly, in this film the three young leads are also non-professionals (James Taylor, Laurie Bird and Dennis Wilson), whose acting is contrasted to the professional style of the wily veteran Warren Oates.

As the narrative in Zabriskie Point gives way, the slow motion sequence, orchestrated to the music of Pink Floyd, takes over the film, which starts to take on the polymorphous perverse quality of a film by Stan Brakhage. Antonioni accomplishes this by using slow motion of different speeds and repetition to the point that the poetics of the film takes over its narrative content and supplants it. Antonioni had many options for the music at his disposal and some of these options remain of interest as it clarifies his final choice. Originally John Fahey and The Doors were meant to play a greater role in the film. Fahey was an American music scholar, composer and musician who absorbed bluegrass, country and blues music into his own work with feigned effortlessness. The Doors wrote the theme for the film, titled L’America, that would end up on their final, classic L.A. Woman album (1971) but Antonioni didn’t like the song and never used it. He also disagreed with Fahey about the music and only used a small portion of his work in the final film, but compensated for that loss with the use of Roscoe Holcomb, an Appalachian banjo player, and the American standard Tennessee Waltz by Patti Page. He also used the first section from The Rolling Stones’ You Got the Silver, where Keith Richards mimicked the sound of an American slide guitar and took the vocal lead. There was also original material from Pink Floyd and Jerry Garcia, in one of his most inspired improvisations on acoustic guitar where he seemed to casually channel Harry Smith’s The Anthology of American Folk Music (1952). The final soundtrack shows that Antonioni was interested in a folk/ psychedelic sound that was not aggressive, in the manner of the Doors, but more exploratory, meditative and open ended.

THE DREAM OF THE SIXTIES

The narrative thread of the film - the genre element - only makes sense after those explosions where we get to see the psychic fault line under the American landscape that was at a boiling point in 1969. Antonioni was able to take all of that hate and make it into art. The dream of the sixties, if there can be said to be such a thing, most certainly ends at the Sunny Dunes project but it is not wholly the fault of greedy capitalist developers. Daria and Mark share that responsibility as they never make plans, they never express their emotional needs and reservations, they never talk about their ideas, they never speak in anything other than clichés. While Mark is portrayed as a silent saint/pagan figure, Daria has a more complex relationship to both Sunny Dunes and the man in charge of it. Her hippie demeanor, the hapless search for a commune in the desert that never materializes, the affairs with two very different men who also fail ultimately to connect or mature in any meaningful way express a failure that she herself is unable to articulate.

This is where we come to the fact that the actors’ names and their characters’ names are the same. The very different courses that their lives took after the critical and financial failure of the film in 1970 is eloquent. Mark Frechette temporarily moved to Italy, joining the expat community of artists in Rome, or Hollywood on the Tiber, as they called it at the time. He made two more films there, Many Wars Ago (1970) by Francesco Rosi, a WWI allegory on the futility of war, and La Grande Scrofa Nera (1971) by Filippo Ottoni, an examination of peasant life in contemporary Italy. After this brief two year period he returned to the USA and along with some accomplices attempted to rob a bank in Boston, Massachusetts in 1973, presumably attempting to raise money for a radical group, similar to the Weather Underground, that naively saw holding up banks as the beginning of a revolutionary strategy to destroy capitalism. Although from Mark’s comments of the time it was clear that the robbery was also an act of political theater – similar to some acts by the Red Brigades in Italy - to awaken the population at large indifferent to politics but in tune with entertainment culture, and force them to consider the meaning of class warfare. Predictably the bank robbers were caught and Mark went to prison where he died two years later at the age of 27. After Zabriskie Point Daria Halprin made one more film, The Jerusalem File (1972), where she played a revolutionary of sorts, but the work was uninspired and lacked a strong, articulate, pictorial sensibility. She then went on to a successful career as a teacher, writer and a therapist using dance and movement as forms of spiritual and physical healing. She founded the Tamalpa Institute in California and authored a book: The Expressive Body in Life, Art and Therapy (2008). Obviously Antonioni understood his actors better than was discerned at the time.

Zabriskie Point, as to be expected, was completely misunderstood and viciously attacked by the mainstream press upon release. Even before its release the Sacramento, California US Attorney’s Office had attempted to shut down production using the bizarre Mann Act – a law created in 1910 prohibiting the export of women across state lines for immoral conduct or debauchery. The orgy sequence in the desert presumably qualified as such an “immoral act,” but the government was unsuccessful in their bid to shut down production.

When the film was finally released in February of 1970 the press was ready with a response to Antonioni’s take on America. While the film received superficial but positive coverage from Look Magazine and Rolling Stone, the majority of the media coverage was brutal and blunt. Time Magazine called the film “simple minded and obvious.” Rex Reed, then a famous and powerful arbiter of taste on television and print said the film was “hilariously awful…uninspired and phony.” The New Yorker – a magazine that espouses the opinions of traditional, wealthy, East Coast intellectuals, and the cause of belles-lettres (such as it is), called the film a “pathetic mess.” Lastly, The New York Times – where the opinions within the top brass of the American ruling elite can be discerned – called the film “one of the worst films of 1970.” The New York Times also reviewed Love Story that year – their title for the review: “Screen: Perfection and a ‘Love Story’: Erich Segal’s Romantic Tale Begins Run.” So much for the press.

ATOMICALLY FROZEN

The down the road ending of Zabriskie Point is a re-staging of Chaplin’s Modern Times (1936) that rings hollow, even without the absurdly romantic song that was tagged on as a coda during the closing credits, without the director’s consent, as surely there is nowhere for Daria to go. She is literally and figuratively in the lowest point in America - a Death Valley – an ancient lake frozen in the time of its own destruction. The intense light and heat that visibly ripples in the air at the end appear as an afterglow that might recur now and again in future decades – like an unwanted flashback. Jean Baudrillard: “No longer explosive, but implosive. We are atomically frozen, subjected to perpetual deterrence. And if the Cold War does not break out, if it does not explode, if, indeed, it is not really intended to explode, it is because its true function is to keep us deterred, chilled... in which all the energy of the real is effectively engulfed, not in a spectacular nuclear explosion, but in a secret and continuous implosion, which is perhaps taking a more deadly turn than all the explosions that presently threaten us.”9 Antonioni would like to be sympathetic but seems in some sense at a loss as to how to proceed. Certainly he believes, like Mark and Daria, that the youth culture that they embody signals a radically different path from that outlined by "Machine America" so beautifully articulated in the brief Sunny Dunes promotional film. As Ian Macdonald put it in his book about the sixties: “... the hippies’ unfashionable perception that we can change the world only by changing ourselves looks in retrospect like a last gasp of the Western soul.”10 David Lynch understood the intellectual and moral nihilism that is to be found in the West after that last gasp and created his own version of the Western and its discontents in the brilliant Lost Highway (1997), where we see a wild West where past, present, and future share the same stage and where Jacques Ellul’s “technological society” reaches endgame.

Zabriskie Point is a different matter. Antonioni’s film has a dramatic power, an intellectual subtlety and a pictorial intelligence that is sublime and undimmed by the passage of time. The authenticity of the film is enhanced by the acting of the leads, and takes hold of the imagination by means of an emotional integrity that is integral to the work as a whole. It is this moral integrity that beautifully mirrors the aspirations of a generation – the generation of what-might-have-been as Tom Hayden called it - that would eventually split into many different directions, in some cases destroying itself in the process. The film captures the moment just before that happened and freezes it for later generations to imaginatively re-enact the role of witness – the word that best sums up Daria Halprin’s role without ever being made explicit. There are many possible definitions of witness but Albert Camus in The Plague defines it best with regard to Zabriskie Point: “He should not be one of those who held their peace but should bear witness in favor of those plague-stricken people; so that some memorial of the injustice and outrage done to them might endure; and to state quite simply what we learn in a time of pestilence: that there are more things to admire in men than to despise.”11

The film was much maligned upon its release but enough time has passed that many of Antonioni’s perceptive observations associating our corporate consumer culture with repression and violence, that at the time seemed fanciful or morbidly disillusioned, now appear prophetic - the film seems to become only more prescient with time. Zabriskie Point is Antonioni’s dark vision of American capitalism, the pragmatic architects of its war/consumer society, and an unruly minority of individualists who wanted, for a brief moment in time, to go in a different direction, all meeting at a crossroads.

Zabriskie Point

1 Seymour Chatman, Antonioni, Or the Surface of the World (University of California Press, 1985)

2 Dennis Hopper, Marin Hopper and Brooke Hayward, Dennis Hopper 1712 North Crescent Heights (Greybull Press, 2001)

3 Marc Augé, Non-Places Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity (Verso Press,1994)

4 Roland Barthes, “The Blue Guide,” in Mythologies (Hill and Wang, 2012)

5 James Rosenquist, Painting Below Zero: Notes on a Life in Art (Alfred Knopf, 2009)

6 Michelangelo Antonioni, The Architecture of Vision: Writings and Interviews On Cinema (Marsilio Press, 1995)

7 Voltaire, God and Human Beings (Prometheus Books, 2010)

8 Diedrich Diederichsen, Zabriskie Point Revisited (Bulletins of the Serving Library #4, Fall 2015)

9 Jean Baudrillard, “Hot Painting: The Inevitable Fate of the Image” in Reconstructing Modernism (MIT Press, 1990)