Doubting Thomas: Photography and Michelangelo Antonioni's Blow-Up

Blow-Up photograph by Don McCullin

Published in CineAction 2013

“What I am is a photographer”, he explains. “To have a job like mine means that I don’t belong to the great community of the mugs: the vast majority of squares who are exploited.”

Absolute Beginners - Colin MacInness

In the 1950’s we became aware of the possibility of seeing the whole world at once, through the great visual matrix that surrounds us; a synthetic, ‘instant’ view. Cinema, television, magazines, newspapers immersed the artist in a total environment and this new visual ambience was photographic.

Collected Words - Richard Hamilton

Julio Cortázar Paris 1958

Blow-Up Credit sequence.

GETTING TO 1966

In 1959 the brilliant and enigmatic writer Julio Cortázar wrote a short story called The Devil’s Drool that would be adapted by Michelangelo Antonioni, Tonino Guerra and Edward Bond in 1966 into Blow-Up. Cortázar, raised in Argentina, had been in exile in Paris since 1951 when he was 37 due to his leftist politics and worked at Unesco as a translator. Having a good steady job Cortázar and his wife held court in Paris in their beautiful apartment for the Spanish speaking exile community. Trips to their famous soiree's were an important part - often a stepping stone - for young writers and emigres into the literary world of the European publishing industry and the press. He, along with other Latin American authors, such as Mario Vargas-Llosa and Manuel Puig, ushered in a new sort of novel that would no longer be tied to the slow, rural realism that had become a trademark style of Latin American writers. There was a new highly urban social matrix that was much more intense, flexible and ambiguous than any that had been experienced before. With a daring borrowed from William Faulkner, Louis Ferdinand Celine, Virginia Woolf, T.S. Eliot and other modernist writers and poets they would tackle contemporary life in a manner that was consciously urban, complex and modern. The resulting stories and novels were paradoxical and matter-of-fact, darkly serious and comical. The novels of the “Boom,” as that movement of the 1950's and 1960's came to be called, best captured the fragmented nature, incipient violence and absurdity of the period. Another major model for the new generation would be the work of the Argentinian Jorge Luis Borges, particularly in his highly complex and unnerving short stories - influenced by Edgar Allan Poe and classical literature - that were disturbing because they suggested a sinister, haunted, and fundamentally unknowable reality, always co-existing under the most prosaic of contemporary settings. In Borges' world everyday life was merely a very thin veneer - a palimpsest - where we caught glimpses of other disturbing realities underneath the familiar everyday world that we could never understand completely but only catch in subjective episodes. In short the glimpse replaced the look in the new work and it was Cortázar who was the most adventurous in his choices.

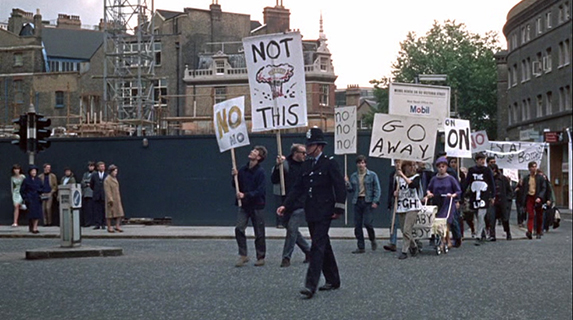

Blow-Up The mimes at the beginning of the film in the London financial district.

Antonioni’s co-writers would both bring crucial elements to bear on Cortázar’s oblique story. Tonino Guerra’s extraordinary facility to construct solidly structured scenarios that were also ambiguous and mysterious made him the perfect choice for Antonioni, who had used him previously in his films from L’Avventura onwards. Edward Bond was a playwright who, along with the other angry young men of his generation, pioneered in theater the use of realistic everyday speech and slang, along with highly naturalistic depictions of sexuality and violence. In Bond’s case this was based on his working class experiences growing up in the north of London during the war. This combination of writing talents worked beautifully to create a seamless screenplay that both remained true to the short story that sparked it and went beyond it in scope and ambition. Nevertheless Cortázar’s story was not, as has been presumed for years, merely an inspiration. Rather, it was both a solid foundation upon which the architecture of the film was grounded, and it conveyed to Antonioni a sense of willful, often sarcastic, narrative ambiguity, a crippling, amoral self-consciousness and a sense of impenetrable dark mystery for which he sought, and found, cinematic equivalents.

The Devil’s Drool is a sixteen page story in which a photographer named Michel living in contemporary (1959) Paris narrates an event in the first person using a laconic and self deprecating prose style. This is how the story begins: “I’ll never know how I’m supposed to tell this, in the first second or third person plural or inventing continuously new forms that wouldn’t be of any use anyway.”[1] He seems strangely removed from events even as he experiences them wandering around Paris seemingly without aim. The casual tone becomes sinister in a very subtle way for we intuit that the instability of the narrator – his offhand dismissal of the idea of a point-of-view - is the subject of the story itself: “I had no desire to take pictures and lit a cigarette just for something to do”[2] He immediately contradicts himself and takes some pictures of a couple kidnapping a boy, he’s not sure, using a very small Contax camera, that was then euphemistically referred to as a spy or detective camera. On returning to his studio he blows up the images he’s taken and what he saw, or what his camera captured, emerges and he ruminates on the horror. Or is that what happened? Here he describes the situation he thinks he saw on crossing one of the islands of the Seine: “Curious that the scene (nothing really, the two there, young in different ways) would have a disquieting aura. I thought that I was making that happen, and that my photograph, if I blew it up, would reconstitute things to their real nature. I would like to have known what the man in the grey hat was thinking, sitting in the front of the car waiting by the dock reading a paper or sleeping. I had just discovered that because people sitting in cars always disappear, they get lost in that miserable private cell that gives them movement and danger. Yet the car had been there all the time forming part (or deforming part) of the island. A car, how to describe it? A beam of light, a bank in a plaza. Never the same light, the sun, always being new on the skin and in the eyes, and the boy and the woman alone as one, put there to alter the island in some way, to show it to me in some new light”[3] The narrator is clearly unreliable. Antonioni, who already had experience translating the prose style of moody novelists, such as the troubled Cesare Pavese in The Girlfriends (1955), took on Cortázar’s story for his second English language film.

Antonioni’s first film in English was one of the three related short films that make up The Vanquished (1953) dealing with an existential crisis present in young people in the postwar period. In this short episode, that could be a first draft of Blow-Up, a young man and would be poet in London kills a woman seemingly for no reason in a park. He then tries to financially profit from the murder by selling his story to a newspaper by pretending to be the person who discovered the body. Liking the attention he’s receiving he cavalierly confesses to the crime that he claims was perfect because it had no logical motive. His story becomes a sensation and he in fact does receive the attention that he craves. The film ends with a perplexed newspaperman phoning in his story from a phone booth while the camera pans away from him to the same park where a couple is playing a game of tennis oblivious to the strange drama that’s unfolding a few meters away from them. In this final incongruous shot of a tennis match unrelated to the narrative in The Vanquished, Antonioni lays the groundwork for his subsequent work of the 1960’s.

Blow-Up

JANE

In Blow-Up we follow a highly successful fashion photographer in the midst of London in 1966. He is now named Thomas, as in doubting Thomas, named after the apostle who refused to believe that Christ had arisen from the grave after his death unless he could see and touch the wounds himself. Thomas wanders from an antique store that he plans on buying as a real estate investment into Maryon Park located in the then gritty low-income area of South East London. There he takes some shots clandestinely of two lovers at play, a young woman named Jane played by Vanessa Redgrave and an older man whom we never meet. Jane sees him and asks Thomas for the film. He refuses and later in his studio after blowing up the negatives sees that in fact he may have recorded a murder in progress. There is apparently a hand holding a gun off to the side behind some bushes. Jane seems to know what’s going on and the man is oblivious. An idyllic encounter that was supposed to finish Thomas’ work in progress, a photography book about the poor in London, seems to have recorded a man’s murder. But of course there are doubts. Thomas returns to the park and finds the body, but it has vanished when he returns with his camera to take a picture of it. In the midst of this Jane turns up at his studio and continues to demand the original negatives to the pictures; this is interrupted by some flirting and the arrival of a propeller from the antique store that Thomas had purchased on a whim. Jane, the mystery woman, leaves with what she thinks are the negatives (that he has switched) and Thomas is left completely in the dark. He decides to investigate what really happened via the images he took in the park, find the woman and solve the mystery. In short he becomes a detective. Siegfried Kracauer described the detective as an essentially modern figure who is on a rational quest for meaning and narrative closure.[4]

It is the detective who uses logic, keen observation and deductive skills to assemble fragmentary details into a meaningful narrative and thereby arrive at the truth, but does he? Blow-Up is a meditation on this question. The sense of dislocation and anxiety in the film are acute but never fully articulated as they would be in a conventional narrative film. For example when the woman in Roman Polanski’s Repulsion (1965) is suffering from dislocation we understand that it is her perceptions which are distorted because she is deranged, not the world, we are merely seeing it through her eyes. Conversely in Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange (1971) it is society that is deranged, having become dislocated from a collective sense of common human values that bind us, and it is the adaptation to that society that is seen as morally reprehensible and comically grotesque. In Blow-Up it is not possible to pinpoint either a trauma in the characters or a social dystopia at work. Antonioni gives us good helpings of the disjunctions and psychological dislocations that we have come to expect from auteur films, but then keeps them in play without resolving them with brilliantly suggestive shots that appear headed toward metaphor or toward a conclusion and then the symbolic evaporates, the possible philosophic explanation becomes muddied with contradictions, the psychological becomes opaque.

Cover to Life is Good and Good for You in New York by William Klein

TERRIBLE TRINITY

The role of Thomas, brilliantly played in the film by David Hemmings, has been touted as being modeled on the photographer David Bailey. As recently as 2007 Kieron Tyler writes: “Blow-Up also subverts London on its journey towards the Summer of Love. Hemmings modeled on David Bailey photographs some top models including Verushka and Peggy Moffitt.”[5] In fact there were several models aside from David Bailey that were used for the role of Thomas. Alongside Bailey, who was then, and remains today, the best known of the younger photographers of that generation, Brian Duffy and Terence Donovan formed the “terrible trinity” a term coined by the press of the time.[6] The young photographers were also called “East Enders” which was a term that not only described a district in London but signified the working class. While previous generations of British photographers, most famously Cecil Beaton, had come from the upper classes, and were featured regularly in traditional journals such as Picture Post and Life, the “terrible trinity” wore their working class origins on their sleeve. A brief window of opportunity had opened in the rigid class system in England that was also happening in art, film, literature, theater and music. These young photographers took on portraiture, journalism and fashion and because of their youth and quick rise to prominence came to be known as “the young meteors”.[7] They shared a similar aesthetic concern with everyday life that was depicted in a way that seemed unaffected by formal or flâneur strategies that, while not completely absent, remained in the background leaving center stage to a content that was often harshly realistic and without a clear narrative arc that explained the action. Their photographs were as direct as a snapshot, an aesthetic that was wholeheartedly embraced.

Other photographers at the time were of course working along similar lines such as Helen Levitt in the United States, Agustin Jimenez in Mexico and Mario Giacomelli in Italy among others. There was also the influence of American post-war action painting with their emphasis on improvisation, emotional integrity, directness and speed as well as William Klein’s influential and groundbreaking book Life is Good & Good for You in New York published in Paris in 1956, and Robert Frank’s The Americans two years later. Klein’s graphically adventurous, high contrast work caught the spirit of the time and place with panache and humor both in his photographs and the brilliant cover that was as radical as his work. The images pivot between a casual, almost laconic, framing with highly deliberate juxtapositions. The liberal use of deep focus allowed Klein to juxtapose not only across the frame but within the deep space created by his creative use of wide angle lenses and fast film. His use of Kodak Tri-X 600 ASA was normally associated with photojournalists who did not have the time to switch films from interior to exterior or sunny and overcast and subsequently the emphasis was on the films versatility. The price paid for this wide range of exposures was a high degree of grain. This graininess was derided at the time, at least in ‘art photography’, and seen as a mark of editorial photography, photojournalism, or worse, amateurishness. Klein not only accepted the grain of high-speed film but reveled in it and emphasized the grain in his printing methods by using high contrast paper and cropping to further increase the grain.

New York 1956 William Klein - Klein's radical open frame, suggesting the poetics of urban spaces, seen to full effect.

Formally his pictures are beautifully articulated with a strong natural sense of how human beings inhabit public spaces. Klein pushed his printing methods toward a graphic style playing off foregrounds and backgrounds as interlocking shapes that then work dramatically together as in musical counterpoint. Organic shapes mirror man made surfaces and the archaic is juxtaposed with the contemporary – particularly in his series on Rome. The effect was revolutionary as the images suggested that it was possible to capture not only the surfaces of urban life, as had been done in the past, but the experience itself translated into an aesthetic plane of black and white. Klein was able to express the moral ambiguities, mysterious narratives that lead nowhere and dramatic/comical collisions of cultures and classes into a poetics of urban space without resorting either to cloying narrative clues or to painterly references common to pictorialism. He along with Robert Frank, Ronald Traeger, Diane Arbus, Werner Bischof and a handful of other photographers created an urban photographic poetics that has been much copied but not equaled. It was precisely this delight in mysterious, unrelated thematic strands within the same frame that attracted Antonioni as well as Federico Fellini who sought to hire Kline as a cinematographer when he was in Rome for his films of the early sixties.

Breathless 1959 Jean-Luc Godard

The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner 1962 Tony Richardson, Allan Sillitoe

The rise of the young meteors can be seen as part of a larger artistic enterprise in which documentary realism and the working class images associated with it were beginning to permeate all areas of the visual arts. It was not just a matter of working class aesthetics but of ethics hence the resistance from the status quo. Allan Silltoe's novel Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner, Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless and Tony Richardson’s Look Back in Anger would be made the same year (1959) that saw the publication of Julio Cortázar’s story that would eventually become Blow-Up. In contrast to the stuffy pictures from the postwar era the work of the young meteors was spontaneous, fresh, sexy, darkly humorous, as influenced by modern graphic design and pop culture as by television and cinema. An important element that made their work particularly British was the influence of the “angry young men” in the theater with plays such as The Entertainer (1957) by John Osborne that depicted everyday situations and speech unfiltered by the polite theatrical conventions of the time that had lost touch with people’s ordinary lives. The “kitchen sink realism” of films such as The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner (1962) set new standards for capturing interior monologues and personal sensibilities and contrasting them with harsh social realities delivered with a freshness usually found only in documentaries. This documentary approach is beautifully expressed in the “Free Cinema” movement that included Ken Loach and Lindsay Anderson, and that captured the complex social fabric with very limited means and a high degree of realism, going even beyond the work of Italian neorealism that still seemed tied to certain conventions of melodrama in their narratives and musical cues. Lastly, the work of the young meteors was also bringing something new: aware of avant-garde cinema and the collages of the British Independent Group, the first group of artists to consciously create pop art as early as the late forties, the younger photographers were not confined to outmoded conventions and restrictions and were free to experiment and explore more demanding and enigmatic kinds of images. The new work was conscious of heterogeneous and often contradictory emotions and illusive sensibilities that were articulated indirectly or obliquely.

John Cowan, photographer Jill Kennington, model exemplify the new photography of the "young meteors" full of energy, enthusiasm, and free of the restrictions of class and sex. Like the image below it is a fantasy image but one predicated on a new sensibility and philosophy.

Della Oake 1950's Cecil Beaton exemplifies the postwar conservatism that suggested the rigid codes of classical painting and the unquestioned authority of the ruling classes. "Normalcy and good taste" were the orders of the day.

THE MOST AMAZING STUDIO IN LONDON

Despite the large number of models available for the character of Thomas perhaps the principal influence on the film was John Cowan who was a gifted photographer of movement. Older than the young meteors he concentrated on fashion shooting in natural light and using actual locations albeit with a high degree of theatrical artifice. It is his photographs that we see in the film as belonging to Thomas and it is also his studio: 39 Princess Place in Notting Hill. The place had been a carriage works in the early 20th century and then a furniture store. In a feature on Cowan in 1965 the Daily Mail called it the most amazing studio in London.[8]John Cowan rented out the immense studio to Antonioni for the filming from May to July in 1966. Cowan also lent technical advice on the process of shooting and developing film and provided authentic details. He was one of the first people in London to have a two way car radio with a call sign Copper 8, a feature adopted by Antonioni as well as Cowan’s penchant for wearing white trousers, for drinking and playing music during shoots, and for a “recklessness that by the end of the decade had forced him to leave London”[9]. The Cowan prints that one sees in Thomas’ studio are from the popular Interpretation of Impact Through Energy (1964) exhibition held in London.[10]

John Cowan and the Young Meteors, would revolutionize photography in a variety of ways, principal among these is the inclusion of movement, natural light and the incidental details of everyday life. While it might seem obvious that these things would have already made their way, by design or by default, into photography, British fashion and editorial photography after the war was tied to certain conventions of gentility, wholesomeness and a sense of theater exemplified by Cecil Beaton and Norman Parkinson as seen in the pages of Vogue during the forties and fifties. This work was slick, artificial and rigidly bound to conventions of “normalcy” and “good taste.” It is this aesthetic that the Young Meteors took on. The first break from the old guard was made by the photographer Tony Armstrong Jones in 1958 with the publication of his book London. The book – even in its title – evokes William Klein’s revolutionary book on New York. As with Klein’s work the images were casual and informal, and their use of natural light made them seem like common snapshots. These aesthetic decisions were brought to the foreground and made to stand on their own as a legitimate artistic practice. The book went off like a bomb in the British photographic world from which the old guard soon recovered by adopting many of the formal properties of the new photography and treating it as a style. This is a common strategy that orthodox artists use when threatened by a new artistic enterprise. In 1958 Armstrong Jones explained his aesthetic: “I use a very small camera, little apparatus and no artificial lighting at all…(photographs) had to be taken fast. It’s no good saying “hold it”…Like trying to hold a breath, you find you’ve lost it.”[11] Ironically Armstrong Jones – later Lord Snowdon – would “reform” and establish himself as celebrity photographer, like Cecil Beaton before him, using the traditional formal lighting and framing that he had helped to displace as it inevitably came back into vogue.

Jane Birkin David Bailey from Box of Pin-Ups

BOX OF PIN-UPS

David Bailey’s justly famous Box of Pin-Ups, a collection of portraits from 1965 brilliantly articulated the crisp high contrast style that was studied and laconic, sexually frank and sarcastic, qualities that captured the moment very well. Francis Wyndham was the writer who did the text for Bailey’s book and was subsequently hired by Antonioni to teach him the habits of the locals and to show him the places where photographers lived – how they conducted their private and public lives. They noted prosaic elements, for example that both the photographers Claude Virgin and David Bailey owned propellers that they used as decoration in their studios and that Bailey owned a Rolls Royce and an antique shop named Carrot on Wheels.[12] Antonioni and his writers met the models Jill Kennington and Verushka in the studio owned by David Montgomery, a fashion photographer that worked regularly for Vogue, where they also noted the use of large glass panels used successfully by Richard Avedon in his influential fashion work and incorporated them into the film. It is David Montgomery who is seen in the opening credits photographing the model Donyale Luna, the first black model to feature regularly in fashion magazines, in Brixton Market.[13]

Blow-Up’s superb art direction was managed by Assheton Gorton whose team added mezzanine walkways and contrasting modern and antique furnishings to Cowan’s loft. Classic and contemporary art are hung alongside Cowan’s black and white prints creating a subtle tension between warring aesthetic styles and periods. A large glass coffee table conspicuously seems to float over a metallic sculpture and on its polished surface sits a large magnifying glass, the essential prop in the murder mystery. Montgomery’s assistant Reg Wilkins was cast as Thomas’ assistant keeping his real name and lackadaisical style in the presence of models casually walking around semi-naked waiting for the moment when they might take part in the city’s fashionable milieu where features such as Young London, May 1966 ”confirmed a new power base”.[14] Assheton Gorton also chose Maryon park as it called to mind the theatrical spatial qualities of de Chirico, “an artist much admired by both Gorton and Antonioni.”[15] Moreover, David Mellor quotes Gorton: “it felt like spectral ground, like an ancient place and contained powerful energies.”[16]

Blow-Up - what is being photographed, an idyllic Adam and Eve in modern dress or a murder?

The first time we see Thomas in Blow-Up: leaving the homeless shelter.

DOSS HOUSE

Thomas shoots fashion for a living but the body of work he seems to really hold dear is a series of photos about the poor in London. When we first see Thomas he is posing as a homeless man spending the evening in what he calls a doss house, or shelter, so he can infiltrate this world. In the morning we see him say goodbye to some men that he’s befriended before cautiously finding his Rolls Royce parked nearby. Thomas is working on a portfolio of photographs of the poor, the unemployed and the down and out that he wants to turn into a book. This the the very sort of book done first by Walker Evans in 1938 and simply titled American Photographs that depicted everyday life, as Evans found it, of people from all walks of life and social classes. Evan’s work was enormously influential to the work of various photographers including the young meteors working in photo-reportage for the Sunday supplements. These news magazines were hugely influential in the postwar era throughout Europe and the United States. What made these photographs different from the usual images seen in photo journals was that the pictures were constructed and laid out as narratives from the start, they were photo-essays and aside from Walker Evans, were influenced by W. Eugene Smith's innovative fusion of narrative conventions, adapted from graphic novels and comic strips, but applied to photojournalism. Another influence was Bill Brandt whose work analyzing the English class system such as The English at Home (1936) set the stage for what was to come. Bill Brandt started to make extreme high contrast prints after being influenced by the work of Gregg Toland in Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane (1941) a film that had a profound influence on Brandt and subsequently on British photography in the sixties.

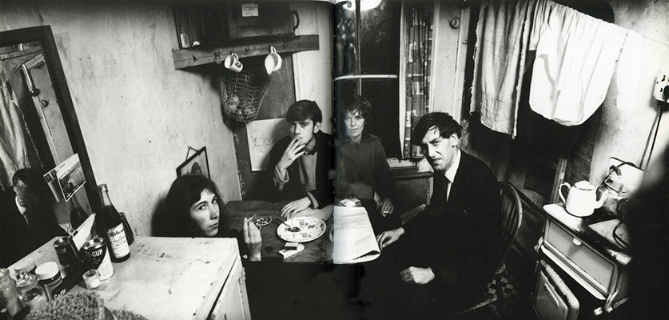

Homeless Aldgate, East End London circa 1963 Don McCullin

FREE LIKE HIM?

Don McCullin, one of the most inspired of the younger photographers was hired by Antonioni to shoot the murder in the park and Thomas’ portfolio of images depicting London’s poor. It is McCullin’s pictures that we see when Thomas begins to blow-up images and search for clues.[17] Thomas’ colleague and editor Ron is to write the captions for the photo book. While meeting in a fashionable restaurant, they decide that the pictures that Thomas took that morning in the park would be perfect for their book as the images appear to be so peaceful and idyllic – even suggesting Adam and Eve in modern day clothes - that it would provide an ideal way to end an otherwise critical and perhaps depressing book on a positive note. Interestingly, the sorts of sudden and unexplained juxtapositions that they are planning are very much in the spirit of Blow-Up itself. They then engage in a brief debate about freedom. Thomas explains that he wants to have “tons of money” so he can be “free.” As a reply Ron points to a portrait by McCullin titled Homeless Aldgate, East End London circa 1963 and says “free like him?" There is no answer from Thomas and the question is left hanging. McCullin’s personal work was inspired by Robert Capa and while often brilliant was, like his mentor’s, graphic, direct and violent. McCullin’s wartime childhood in the slums of Finsbury Park was where he learned, as a self-taught artist, to use photography descriptively and where we first see the direct hard lyricism that he would become known for. His first published pictures would be of a street gang from his neighborhood. He would eventually give up his successful career as a street photographer for work in Vietnam and subsequent wars, but in the mid sixties he was engaged in a profound examination of the grueling class wars in post-war Europe.

Don McCullin London 1964

The pictures that the young meteors published in the Sunday papers were intensely felt photographs that were seen by the general public on a weekly basis. The approach that the young British photojournalists in the 1960’s took was blunt and confrontational with both their subjects and their viewers. They were fearless and relentless and the resulting images were often brilliant, direct and profoundly disturbing. Among the most effective photo stories of the time were Terence Donovan’s series Strippers for the magazine About Town. The series depicted women who worked in strip clubs, but the pictures were not voyeuristic shots of naked women on stage or in the dressing room. Donovan showed them walking home after work, shopping for groceries or watching television at home. Keeping his distance Donovan not only captured the details of their lives but just as importantly the social context in which those lives were experienced.

Strippers Terence Donovan

East End David Bailey

Unemployed Glasgow Penny Tweedie

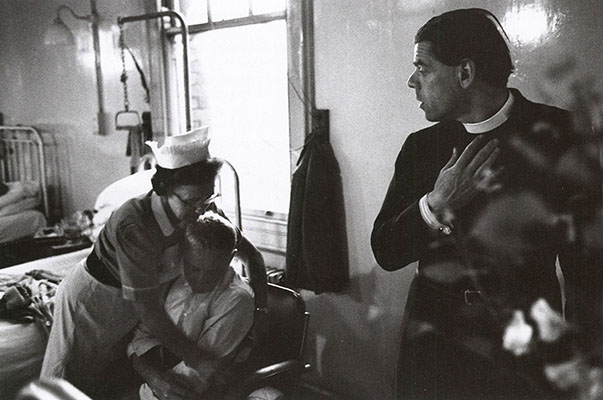

A Mission's Failure Ian Berry

David Bailey did a whole series on the social workers of East End slums (where he was born and raised) for About Town. In Bailey’s framing we can see him not just observing people move through some indefinite urban space but making connections between individuals and the places they inhabit intimately. Pennie Tweedie, one of the few working women photographers at the time, did a body of work on the unemployed in Glasgow stressing the psychological strain of poverty and enclosed spaces for the Shelter. In one of the most intense photo-narratives Ian Berry did a body of work titled A Mission's Failure for the Observer about the failure of a priest to make a difference to the poor and elderly in a retirement center. Berry traced the priest’s journey from an idealist ready to save lives and souls, to his journey inside the slums of South London and his disastrous confrontation with men who were angry, fatigued and who saw the priest as an authority figure that they could finally lash out at. Berry’s work was profoundly influenced by W. Eugene Smith’s innovative fusion of narrative conventions, adapted from graphic novels and comic strips, but applied to photojournalism. The resulting visual story was brutally honest and direct, capturing the awkwardness and the tensions present in a way rarely seen at the time. For that matter we rarely see this now since this kind of emotionally devastating presentation of reality with none of the rough edges removed has never been popular with institutional, corporate or state sponsored enterprises such as those that we can see today in newspapers, magazines, and television that all presumably deal with news or reality in some capacity. With A Mission’s Failure photojournalism reached a high degree of poetics grounded in everyday life that was shocking but also emotionally involving, because the material dealt with poverty and old age not as a rhetoric, as was common in propaganda and avant-garde practice, but as first-hand observation that held back direct judgment and allowed the viewer space to develop their own ideas.

World's End Pub KIng's Road, Chelsea April 3, 1963 John Cowan photographer Jill Kennington model

MOVEMENT AS DELIGHT

While John Cowan was a primarily a fashion photographer he was also influenced by the young meteors and created work that consciously melded fashion with everyday street photography and photojournalism, seamlessly referencing all of them without settling on any. This was not so much a conceptual choice but a method chosen purely for the pleasure it gave, similar to William Klein’s series for Vogue (1962) in which models carry large mirrors through a busy New York City intersection, melding street photography with fashion. Cowan used the reality of London as a stage on which to play out the standard narratives associated with the conventions of fashion. Cowan’s break came in 1962. In a series of photographs for Queen magazine he photographed the model Jill Kennington standing on top of or next to various neoclassical statues throughout London mimicking their poses and gestures but in an offhand, playful, often sarcastic manner. Not since Chaplin’s opening in City Lights had someone thumbed their nose at neoclassicism is such a direct way in a populist medium. It both pointed back to Chaplin’s film and forward to the Vaudevillian style of Monty Python, Derek Jarman and Peter Greenaway in British cinema in their use of classical motifs as comic foils, playing the straight man to the more urgent physical realities common to everyday life. The athletic Kennington physically climbed up to the statues several meters off the ground in their pedestals and mimicked their heroic gestures for long periods while Cowan got his shots. Their collaboration is a brilliant satire of the seriousness and stodginess of classicism and simultaneously a celebration of “movement as delight” brought up-to-the-minute by Kennington’s gestures of ecstatic dance-like movements in a contemporary urban milieu. Their integration of everyday life into fashion would also break taboos of class, race and sexual segregation as in the magnificent shot of Kennington titled World's End Pub KIng's Road, Chelsea April 3, 1963. Kennington is dressed in a bikini in a working man’s pub interrupting a game of cards with an impromptu table dance, created on the spot by a rainstorm that made shooting outdoors impossible.[18] The photograph seems to encapsulate new-wave cinema in a single shot, as various people of contrasting class, age and sex all suddenly finding themselves sharing the same stage. This interaction of ebullient theatricality with real life would become a trademark style of their collaboration in subsequent years.

These sorts of ironic juxtapositions had been seen before of course in the work of the New York School exemplified by Robert Frank, Louis Faurer, Diane Arbus and Saul Leiter but in their work these urban fragments were often perceived to express alienation, loneliness and displacement which are all serious themes that would satisfy academics and museum curators because they fit easily into preexisting art historical narratives. Even contemporary photographers such as Nick Waplington in his series titled Indecisive Momento (1999) work along similar lines as those set by the New York School. That is they are primarily about chance encounters, alienation and the absurd. With Cowan and Kennington these paradoxes and chance encounters are perceived ecstatically and this is accomplished by Cowan’s sense of play and improvisation with his partner rather than with any kind of detachment or voyeurism. The key of course is that they are partners and they are making things happen together. This is clear in the pictures and becomes a major thematic element in their body of work as a whole, as much as the interplay between Anna Karina and Godard would inform their work and of course Monica Vitti and Antonioni in their intense four year partnership.

Blow-Up The protest march near the beginning of the film that is juxtaposed with the mimes and Thomas driving his Rolls Royce through London - he accepts the offering of the "no" sign as a token but immediately looses it.

The spectacular rise of Cowan, Bailey, McCullin, and of the young meteors as a whole, can be seen as part of a larger enterprise in which documentary realism and it’s confrontation with the social problems of working people and of the poor and unemployed would take center stage. This ethical class-consciousness within aesthetics was something that was keenly debated in the postwar era not simply by academics, but by the general population, as the effect of artists who had lent their services to fascist causes such as Leni Riefenstahl or Ezra Pound, were still very present in people’s minds and much discussed. Don McCullin himself had mixed feelings about Antonioni’s film, feeling uneasy about the use of these two very distinct orders of photographic signs – fashion and photojournalism. McCullin sensed that the view of life that interested Antonioni represented a transition from the moment of late fifties, early sixties social realism to a glossy, modernized pop exemplified by American consumer culture. In his autobiography McCullin put it this way: “Style had become everything, now that we had left the social realism of the angry young man behind.”[19] McCullin’s doubts would in a sense be incorporated into the film itself as Antonioni carefully juxtaposed one kind of photography – social realism – with another – fashion – but to what end?

Blow-Up

UNCONSCIOUSLY RECORDED

By a wonderful paradox at the heart of the photographic enterprise the closer one gets to something in an image by blowing it up the more it evaporates into mere pointillist abstraction. When Thomas clips his photographs to a line in order to create a narrative, literally hanging by a thread, it is an attempt to understand what these photographs might be about and what is really in them. While they somewhat resemble a story-board as Thomas, and Antonioni’s camera pan, read them left to right they cannot be reduced to this convenient metaphor. Story-boards map out the way continuity will be used in the shooting and editing of a film bound by storytelling conventions that involve a coherent plot, explainable motivations and actions that move the narrative toward a resolution. This is clearly not the case here. While Antonioni was known to go to great pains in pre-production Blow-Up uses all of the conventions common to the European feature film to undermine the rationalist foundations found in those very conventions, but why? Was it, as some writers, such as Pauline Kael, surmised, merely a stubborn refusal to go along with the program by adding some confusion and vagueness to a conventional murder mystery with pretty people? Certainly the idea that photographs in fact reveal more than what the photographer remembers seeing was hardly new. Henry Fox Talbot, one of the inventors of photography, in his book The Pencil of Nature (1846) wrote "It frequently happens...that the operator himself discovers on examination, perhaps long afterwards, that he has depicted many things that he had no notion of at the time...sometimes inscriptions and dates are found upon the buildings or printed placards, most irrelevant, are discovered upon their walls. Sometimes a distant dial-plate is seen, and upon it - unconsciously recorded - the hour of the day at which the view was taken." That term "unconsciously recorded" could be the subtitle to Blow-Up. Fox Talbot suggests, ironically, that a photographer might take a picture of a public clock that categorically states the very minute the picture was taken, without the photographer having noticed it, until later upon seeing and examining the print. The embryo of Blow-Up was already in Fox-Talbot's mind when he wrote this classic text, now considered the first photographically illustrated book.

Une Semaine de Bonte Max Ernst

Blow-Up's radical undermining of seemingly rational narratives was also not new. Surrealists had mined the territory since the early 20th century, creating presumably rational narratives, only to, with a certain adolescent delight, pull out the rug from under them and show the whole enterprise of traditional narrative itself to be a grotesque fantasy machine predicated on bourgeoisie conventions that were a joke – often in more ways than one. Surrealists loved to find the sexual subtexts of presumably wholesome or pedagogic narrative tropes. Max Ernst's wonderful collage novel Une Semaine de Bonte (A Week of Kindness) used 18th and 19th century engravings that often had a sentimental or religious theme as their original purpose. In this masterpiece of the graphic novel narratives meant to reinforce the institutions of the ruling class, as well as church and state are turned on their head. But surrealists depended heavily on the assumption that irrational impulses, that sooner or later come to the fore (as per the writings of Sigmund Freud), were the predominant agency in all human endeavors. In a sense surrealism was merely an inversion of realism, that is, the irrational comes to be seen as the fundamental mainspring of human action. Blow-Up rejects both the surrealist assumption, that the irrational is the determining factor in human consciousness, as we can see in the work of Luis Buñuel - beautifully illustrated in his film The Phantom of Liberty (1974) - and its absurd episodes in which one non sequitur follows another. This programmatic anti-rationalism owes much to the work of Breton and Ernst; Blow-Up also rejects the rationalist impulses of the traditional detective mystery, in the manner of Alfred Hitchcock, clearly evident in his coda to Psycho (1960) that presumably explains the motivation of the main character, and ties up all of the loose ends in the final shot, as the car that contains the murder victim is brought to the surface, returning from the "subconscious" to the light of day - the "conscious." Why does Antonioni reject these narrative strategies and what is this new narrative trope that he is searching for?

We return to Freud. In his Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis, he compares the "images" that are enduringly inscribed on the unconscious to a photographic negative, the unconscious to a room, in which negatives are stored, and the "images" that reach consciousness to a finished print. He then compares the mechanisms by which a mental process begins with an unconscious phase and passes over into the conscious stage "just as a photographic picture begins as a negative and only becomes a picture after being turned into a positive." We see that for Freud the mechanical development of photographs, culminating in a readable positive image, was a ready-made metaphor for the complex mental development that he was trying to describe. Blow-Up carefully navigates outside of these two powerful narrative forms - traditional, or rational and surrealist anti-rational - and finds a different way to adopt the photographic metaphor that Freud used so ingeniously in his seminal book on psychoanalysis.

Blow-Up

Blow-Up

NEOREALIST ROOTS

According to Mary Watt Blow-Up is a “parody of the neorealist tradition…a closer look at the character (of Thomas) suggests that Antonioni, in addition to using typology to explicate the allegorical significance of Thomas has also relied on it to create a parodic (sic) relationship between the modern photographer and the gospel figure which in turn, desacralizes the neorealist project and its attempts at truth telling.”[20] Watt’s astute analysis of the film’s subtext as a parody of neorealism, a movement to which Antonioni contributed from his very first short film People of the Po Valley, allows us to see the character of Thomas in a new light as a version of the director himself as a young man. Watt continues: “we can see that at his most essential Thomas is the “twin” of Antonioni.”[21] Watt’s analysis suggests that Antonioni is thinking about his neorealist roots, as did Fellini when he made the short Matrimonial Agency (1953) in which a werewolf attempts to find a female companion using an agency. This unlikely story is shot using all of the conventions of neorealism thereby completely subverting the very form he is using through irony and parody. But Blow-Up cannot be summarized in this way because it turns the film, as happens with almost all parody, into a polemical work created to mock or to trivialize its subject. Watt again: “…Thomas’ belief that he might know through his camera is mocked. In that moment so too is the viewer’s faith in verisimilitude and indeed, in the recorded image, ridiculed”[22] Watt’s discussion links Blow-Up to The Devil’s Drool, since Cortázar was also using the meandering enigmatic prose style of its narrator ironically to undermine the very rational conventions of narrative that were being deployed. Nevertheless there is a problem, as Antonioni’s use of parody as a subtext cannot detract us from the director’s more ambitious aims that make his film a far more difficult film to pin down. What we have in Blow-Up is a search for meaning that questions the validity of established forms and conventions in photography, painting and film to understand reality or meaning at all. Evidence becomes enigmatic, logical deduction finds only a mess of contradictions, conversation only leads to confusion, photography cannot clarify, consciousness comes up against its own limits. But Antonioni doesn’t leave it there as he uses Thomas, or as Watt calls him his “twin,” to explore the meaning behind his failure to find a complete, unconditional meaning or truth. Antonioni put it himself succinctly: “I am a person who has things he wants to show, rather than things to say. There are times the two concepts coincide, and then we arrive at a work of art.”[23]

On the left Zapruder Kennedy assassination film frame #317. On the right a magnification of John Kennedy's head from the same frame.

Watt also briefly mentions that Blow-Up was released in a time of recent viewing of photographic evidence in the Zapruder film of the Kennedy assassination in Dallas on November 1963. Throughout the sixties this was the most scrutinized short film in history, although a full print was not legally available until 1975 due to the copyright ownership of Time-Life. This was also the first time that the population at large through magazines, books and television programs were shown a close second by second, frame-by-frame analysis of a film. Only certain avant-garde works such as Chris Marker’s La Jette (1962) had really bothered to explore individual frames to such a degree. While Hitchcock brilliantly anticipated this fascination with a pictorialized imagination and the solution to a crime in Rear Window (1954) he held onto conventional narrative structures that Antonioni rejected. In the Zapruder film, particularly as it was shown on television, time was broken down to 1 frame a second, while some particularly important frames, of the trajectory of the famous "magic bullet" or the grassy knoll where a second gunman might or might not be hiding, were blown-up and explored in depth as photographic enlargements. The results were, as one would expect, inconclusive. The more Zapruder’s film was blown-up the less it revealed and the more it suggested.

THE SECRETS HIDDEN IN THE PICTORIAL SPACE

Another possibility might be that Thomas is creating a proto-cinematic collage that connects him to Eadweard Muybridge and other early photographers of movement. This is articulated by Warren Neidich: “Blow-Up…is part of a much larger impulse of 1960’s avant-garde cinema to connect cinema to its proto-cinematic roots: the motion studies of Etienne-Jules Marey and Eadweard Muybridge, and the single long takes of the earlier Lumière Brothers’ films…The process of mechanical reproduction (both his use of the camera and the enlarger) and collage (his reassembly of the images on the studio wall) that define Thomas’ investigation of the “real,” are a regression of cinema to its ancestral derivations in photography of the late nineteenth century. The evolving scene of the murder is deconstructed into a set of motion studies. Film is montaged (sic) into the photo-still and through this process the true nature of reality unfolds.”[24] The experimental works by Muybridge and Marey were attempts to answer long held questions about movement that had preoccupied people for centuries. Some of the questions asked were as pedestrian as: Does a horse ever leave the ground on all four limbs while galloping? The answer turned out to be yes. Others were more abstract: Is there a limit to how time can be broken down into fractions or is there a point at which one can go no further and if so where is that point? They of course wanted to understand how things moved in duration but their scientific research was also a sensuous exploration through photography of time and its relationship to an event.

Eadweard Muybridge The Horse in Motion

Blow-Up Thomas inspects one of his own images.

Mr. Neidich would like to turn Blow-Up into an illustration of a calculated investigation, via post-structuralism, into “the real”: “Only after a series of “blow-ups” …do the secrets that lay hidden in the pictorial space fully emerge.”[25] Do the secrets hidden in the pictorial space fully emerge? I would say the contrary that they multiply as Thomas sips his wine while trying to make sense of it all. The photographer cannot get closer to the truth of the moment that he photographed either by coming in closer to parts of his negative by blowing the image up, or by examining the image with a magnifying glass, or by the selection of different images into a cogent narrative. Blow-Up beautifully leaves out any possible clearly defined resolution to the problem of narration that it has set up teasing possible solutions into and out of the narrative with incredible dexterity. The visual architecture of the film is beautifully balanced and its illusive complexities are handled with a bravura absent from Antonioni’s earlier work. There is nothing in the film that is explicit or exact, everything is casually oblique, in flux and unstable. While Antonioni’s work anticipates the doubt and paradox that are crucial elements of post-structuralism Blow-Up and Antonioni’s body of work as a whole is much closer to Albert Camus’s melancholy skepticism grounded in a profound appreciation of sense experience and mortality.

Blow-Up Gillian Hills, Jane Birkin

SEAMLESS

It becomes clear from the juxtaposition of events in the narration that using photography as a means to uncover layers of reality and arrive at some fundamental truth is also in some sense connected to sexual desire. We see this same relationship later in Antonioni’s Identification of a Woman (1982) in which a film director’s search for themes in his film, locations and sexual companionship are so interrelated that we can say the boundaries between them are not simply unclear but that they have been obliterated on purpose. In Blow-Up it is no coincidence that Thomas’ probing of his photographs is interrupted by an orgy with two aspiring models. It’s as if the sexual act were a displacement of the need to know, or vice versa as the two at that point become fused in an orgasmic release, but a release that only leads to more desire and anxiety and a greater need to know.

Blow-Up David Hemmings as Thomas looks for clues.

Blow-Up David Hemmings, Jane Birkin and Gillian Hills

The orgy takes place on an enormous strip of purple paper that has been unwound from its spool during foreplay. Significantly this kind of paper is called a seamless and its purpose is to eliminate the horizon line that separates the ground from the sky, or the floor from the wall, creating a seamless space for portraiture in which the sitter appears to be in an undefined space (rather that a place) without any clues regarding social context. In short messy reality is absent as the seamless is as clean as a new dissecting table. Irving Penn and Richard Avedon were the acknowledged masters of this kind of photography in the US at the time of Blow-Up and the “terrible trinity” all used the seamless throughout their careers for their bread and butter work. The seamless continues to be used today by a wide range of photographers in art and commerce as it is part of a photographic convention that is so commonplace that it is invisible. Its significance in the orgy is that the sexual act literally and figuratively rips this seamless to pieces, it is left a shambles with wet spots, creases and tears. Not at all the sort of thing that could be used to create conventional portraits as reality has left its mark. Antonioni luxuriates on the purple surface that has left traces of humans and their movements. The sand in Zabriskie Point temporarily etched by the orgy of copulating couples serves a similar function of gravitas – a poetic memento of the function of lost time that Muybridge was so at pains to stop.

WHO THE HELL WERE YOU WITH LAST NIGHT?

One constant charge that has been leveled against Thomas since the film’s release is that he is a voyeur and a misogynist therefore his search for Jane, the mystery woman, merely follows the typical male who suffers from these psychological problems. That is, he objectifies women and chases after those that he can’t have, while he treats those within reach, such as the two models in the orgy sequence, with contempt. While Thomas’ treatment of women, or of people generally, is questionable the terms voyeur and misogynist are incorrect as the hardened and cynical male exterior that he projects is seen to be a veneer learned over the years in the industry to which he has climbed to the top. David Hemming’s portrait is highly realistic as he subtly confers contradictory gestures relating to who Thomas might be. There are several such moments but let’s look at one that is especially apt.

David Hemmings’ Thomas and Jane engage in a brief conversation in his loft. They smoke cigarettes, listen to jazz and flirt but there is also a sense in the film that Thomas has become genuinely interested in this person, and it is also clear that Jane, while perhaps sexually attracted to Thomas, is simply playing for time. The fact that he spends huge amounts of energy doing things like leaping to the floor to answer a telephone to charm and amuse her tells us something, since we see that it is usually women who must work hard in order to amuse him. It is clear that he is used to talking with strong women, he has a facility for it and it gives him pleasure. Women usually also enjoy talking to such a man because they can talk as equals. Most importantly they create this equality together organically in their very interaction, without the need of a law or a politically correct social convention that is in place and that forces that equality as a fait accompli. A misogynist is a person who is afraid of women and who subconsciously transfers this fear into hate. Such a person would be terrified of a person as strong as Jane obviously is and so the charge of misogyny does not hold.

Blow-Up Verushka, David Hemmings The shot and the counter shot occupy the same space via a reflection, as the female and male occupy completely different psychological spaces.

Blow-Up David Hemmings, Vanessa Redgrave Thomas pretends to offer Jane the negatives from the pictures in the park. The seamless and the architectural support put the characters within a visual parenthesis.

What is certain in that for Thomas sexual attraction or the emotional connections between him and the women in his life is highly predicated on the visual. This is made clear when we first see the model Verushka – apparently Thomas’ sometime girlfriend – in a glass reflection sitting on the floor. Thomas flicks the glass so the reflection vibrates and it is clear from this that for him she is to a certain degree an image, as her head is beautifully framed by another image (taken by John Cowan) of a long caravan of travelers in the desert seen from a great distance. Thomas’ sensualized avidity for the visual is a form of Scopohilia, an English translation of Freud’s Schaulust or “pleasure in seeing,” a condition that is wholly characteristic of someone in Thomas’ profession. His only response to her presence is to say with feigned casualness: “Who the hell were you with last night?” Verushka answers Thomas’ question with a sarcastic laugh and a shrug, repaying his feigned casualness with her own. Then they get down to work. It is clear that for them this means a creative act of improvisation, with highly theatrical, dance like movements and emotive actions on the model’s part and encouraging gestures and shouts from the photographer. This becomes a beautiful call-and-response duet for dancer and cameraman. Thomas’ purple shirt, and the cool blues whites and greys of the loft space perfectly counterpoint the magnificent sexual dance that Verushka and Thomas perform on the floor while he takes pictures. The creative and the sexual act for the two at that point fuse into one.

Blow-Up Verushka, David Hemmings. The creative and the sexual act fuse into one.

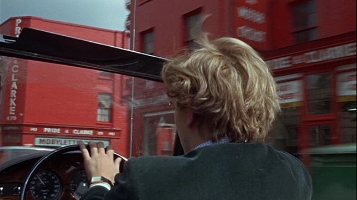

Blow-Up Thomas driving his convertible. Color within narrative.

THE TINY SPARK OF CONTINGENCY

The brilliant use of color in Blow-Up is carefully measured even in presumably casual images that are on screen only a few seconds such as the brief point-of-view shots from Thomas’ car as he drives through London shot in early morning light. Antonioni takes many of the ideas about color announced in Red Desert and develops them further, exploring through attention to detail. While the earlier film uses color in a very calculated, classical, studied way creating composed static shots that express alienation and separation from Nature, Blow-Up has a more complex but apparently casual, even documentary feel to much of the work, a more open approach that is loaded with cultural contrasts and urban energy. The formalities and decorum of the earlier films are gone as Antonioni is pushing his material into new ground. In the same driving sequence early in the film a bright yellow truck passing quickly in front of the camera turns the screen into a field of cadmium yellow. The master cinematographer Carlo di Palma used crisp high contrast color mimicking the work of the young fashion photographers matching their astute balance of theater and artifice with realism. The director had many of the shop fronts painted red and black, and he had some of the grass and the tree in the park that Thomas hides behind while taking pictures painted with translucent purple paint.[26] This ties the park and the studio together integrating them pictorially and thematically. This formalist approach to color is something we would expect from a filmmaker such as Hollis Frampton, but unlike formalist films the properties of pure color are never separated from the documentary component that captures the street life of London in 1966. In fact this setting becomes a major player in the film, as much as the islands off the Italian coast play a major role in L’Avventura. These two aspects, the documentary and the formal, are in sync and edited musically as in counterpoint and then literally set to the music of Herbie Hancock, then working in a style of modal jazz derived from Miles Davis, very sympathetic to Antonioni’s aesthetic.

Blow-Up Jane shouting "Stop it!" Photograph by Don McCullin.

BEING AND PASSAGE

Blow-Up constitutes a refusal at several levels of discourse simultaneously and this aspect of the film is in direct proportion to its obsessive fascination with images. The photograph that best sums up this refusal is Vanessa Redgrave as Jane, the mystery woman, raising her arm up to cover her face with her hand and at the same time saying “Stop it!” We see it once as part of the action of the film and a second time as a black and white still image as Thomas sets up his pictures to attempt to make some sense of it all. In the story by Cortázar the photographer says: “…that my photograph, if I blew it up, would reconstitute things to their real nature.”[27] The photographer believes in photography as a means not simply to capture a fragment of mediated reality but to restore things to their original nature. Like the photographer in Godard’s Le Petit Soldat (1963) Michel/Thomas might say “photography is truth and film is truth 24 times a second.”[28] The photographer is after a Newtonian reality that he can seize literally at the push of a button (or a shutter). What he finds instead is a world described by Heisenberg and Bohr in which the viewer’s respective reality is relative to other realities in an almost infinite possible arrangement of intersections. The big or objective picture turns out to be a fantasy, first, because the viewer is in flux and exists only in relation to other observers, and secondly because the viewer affects the event in ways that remain unforeseen and unknowable.

What Cortazar’s story and Antonioni’s film suggests is that there is in fact no objective viewpoint or essence or single truth at all. Rhetorical categories that presume such an essence, such as the word “being,” are in effect chimeras. If this is the case then reality must in some fundamental way be un-photographable. We come around to Montaigne: “I do not depict being, I depict passage.” Blow-Up might be the story of a man who sought out being and discovered passage. The film repeatedly questions the very possibility of conventional narratives and modes of representation to create order and meaning except through a process of over-simplification and reduction to accepted categories. In Blow-Up the full depth of reality, or at least one aspect of it, with ambiguities intact, is for once allowed space to exist in a feature film. This is what makes this film unique and why the arrangement of Thomas’ pictures in his studio, the sequence from the park, is neither a storyboard illustrating a basic murder plot using traditional storytelling conventions, that is continuity, or its opposite, a storyboard using a fragmented collage aesthetic, that is discontinuity.

A WALK IN THE PARK

The film suggests rather than explains, it questions rather than expounds. For example when Thomas leaves the antique shop and casually decides to take a walk in the park for the first time the director shifts the camera angle from Thomas facing the shop in medium close-up to inside the park from some distance away as the photographer makes the fateful decision to enter, suggesting some larger design or power at work, or even an unknown point-of-view. The moment we enter the park the wind rustling the branches is emphasized on the soundtrack, as if the natural world were announcing its entrance at the same moment as this uncertain point-of-view makes itself felt. This creates a beautiful sense of unease, that is paradoxical since a park is precisely where we are meant to go and experience the pleasures of a civilized oasis that simulates nature for our pleasure, hence the ubiquity of lovers in a park. This oasis is there to act as a counterpoint to urban danger and speed and is a place to rest the eyes, perhaps to lower our defenses. In Blow-Up the park and its mysterious woman with a secret becomes another expulsion from Eden, an Arcadia that already hopelessly corrupted by an unknown reality, a fall that seems to keep recurring as in a dream. Thomas returns to the park four times in the course of the film whose fictional time frame lasts approximately 24 hours.

Blow-Up Thomas seen from inside the antique shop - in effect he is framed while the bust on the right suggest a point-of-view.

It is the trip to the antique shop that first makes Thomas aware of the park, and it clearly acts as a guiding station that points the way - it is a port of entry or toll on a bridge that links two different worlds. The shop seems to house leftovers and cultural artifacts from centuries, a repository of things that have by chance survived into the 20th century. As Thomas comes to the shop we see him from its overcrowded interior space framed by its door with a bust on right seemingly looking on the framed scene outside. This again strongly suggests a point-of-view but does not make it explicit. The crusty old shopkeeper literally blows the dust of history onto Thomas’ face, a gesture certain to make him leave. Rather than being angry Thomas seems bemused and goes to talk to the young woman who runs the shop. She complains that she’s fed up with antiques and wants to move to Nepal. Thomas is charmed and replies: “Nepal is all antiques.” “Then perhaps Morocco” says the young woman. Significantly Thomas is buying the antique store and will in a sense come into possession of all of the cultural history contained there. It is no wonder that he is fascinated by the shop and takes several pictures of it before walking into the park proper. It is the only moment in the film in which we see him indulge in street photography.

FASHION AND PHOTOJOURNALISM

One key to understanding Thomas’ dilemma is by looking at the two kinds of photography that he wants to master. There is on the one hand fashion photography that has a hopelessly fetishistic relation to the surface of things; and there is documentary work that seeks to pass beyond the surface of things and understand reality in all its messy complexity. Our photographer/detective has a certain underlying contempt for fashion despite the fact that he is obviously good at it and it earns him a fabulous income. And perhaps for this very reason, it is a field that he has already conquered. He also places a great deal of faith in documentary, a field in which he has yet to prove himself. Why the anger towards fashion that he can freely exhibit in front of his models and the idealization of photojournalism? This is John Berger: “During the second half of the 20th century the judgment of history has been abandoned by all except the underprivileged and dispossessed. The industrialized ‘developed’ world, terrified of the past, blind to the future lives within an opportunism which has emptied the principle of justice of all credibility. Such opportunism turns everything – nature, history, suffering, other people, catastrophes, sport, sex, politics – into spectacle. And the implement used to do this – until the act becomes so habitual that the conditioned imagination may do it alone – is the camera.”[29] Susan Sontag articulates a similar idea more succinctly: “A capitalist society requires a culture based on images. It needs to furnish vast amounts of entertainment in order to stimulate buying and anaesthetize the injuries of class, race and sex.”[30]

Thomas constructs a portfolio of images of the underclass as a counterbalance to his fashion work that he sees, correctly, as simply a cog in the machinery of spectacle. In a sense in fashion he is merely a tool of the corporate state, albeit a very well paid tool. His work in the poor house, where he has just spent the night the first time we see him, is the necessary dose of reality necessary for his own sanity and sense of self-worth as an artist. But the photographs in the park are another matter. They resist the summarizing truths of metaphor and genre typical of photojournalism, a medium devoted to illustrating the suffering of the disenfranchised, the injured and the dead. Although Thomas’ pictures record a murder they don’t fit into the category of photojournalism. Paradoxically the images also resist the facile fascination with beauty typical of fashion, despite the fact that a beautiful woman has been photographed in a lovely park. They simply don’t work in the categories of fashion or documentary, but they implicitly reference both. The photograph that captures reality escapes the categories of genre by which we come to understand photography – it’s the photograph that cannot be named.

Blow-Up Homeless shelter where Thomas spends the night to get his shots of the down and out.

Blow-Up Models pose for Thomas. The artificiality is emphasized with the plastic panels while the space itself forms a box that parodies the camera.

Blow-Up Thomas shooting - note the John Cowan prints in the background - on the left a woman floating through the air and on the right a man about to plunge into the sea - and the photographer as master of the elements - but is he?

A HALL OF MIRRORS

In a sense Thomas has intimations of the themes articulated in the film when he attempts to construct a narrative using the pictures he took in the park, but he cannot successfully extrapolate any meaning from them. The film does, exploring this mysterious, highly charged and unstable space in a way suggested by Thomas’ pictures from different angles. The film does this by asking questions: How does the art component of photography, its various aesthetic properties, affect the documentary or representational component and vice-versa? What role does genre and literary/historical narrative play in how we read and categorize images? How does photography redefine spatial relations? Does photography transcend spectatorship? Is photographic space inherently rational? Are signs and meaning in photographs active and in flux or are they frozen and static, or is it some combination of the two and if so how does it work? What is the relationship between a photographer’s subjectivity and his choice of point-of-view? Can an image be impossible to understand?

Antonioni does not answer such questions but poses them in ways that anticipate the critical reactions to images by critics such as Jean Baudrillard, Jacques Ranciere, Jonathan Crary, Susan Sontag and Gilles Deleuze later in the century. For example Baudrillard claims that the massive proliferation and saturation of images in a media obsessed culture and the resultant mediation of reality by images is fundamentally antagonistic to lived experience. In Baudrillard’s language we as a culture have “murdered” the real and created a world in which simulation has become not simply analogous to but inherent to the thing itself, therefore we are immersed in fantasy, a hall of mirrors that makes it impossible to distinguish true from false. Antonioni’s film captures the formation or the foundations of this new world as it was taking shape.

Blow-Up Vanessa Redgrave as Jane and the camera both in perfect focus but the framing emphasizes the flat geometry of the space.

Blow-Up David Hemmings, Vanessa Redgrave. Thomas suggesting to Jane that in listening to music she must "go against the beat."

A PARALLEL UNIVERSE

Thomas remarks on his first and only conversation in his studio with Jane, the mystery woman played by Vanessa Redgrave, that she has what it takes to be a model because “not many girls can stand like that.” She is of course at the heart of the mystery. In a strange sense it’s her narrative, she is in control of it, as so often happens in Antonioni films women seem to subtly permeate what Pasolini helpfully called “the camera consciousness”[31] of the film. She straddles various possible identities that we have come to know from genre films but does not snugly fit any of them. She could almost be a femme fatale but not quite. She is beautiful enough to be a model but the look on her face is lived in and her nervous demeanor speaks of conflicting emotions and doubts that are not the stuff of fashion. She could be the bright and mature woman that is the mate that Thomas needs but not quite. She looks at her watch in the midst of a flirtatious laugh and realizes that it’s time to go with the earnestness of someone who already has a serious schedule to keep and no time to lose on casual fun. She doesn’t take Thomas very seriously. Then what is she? Our clues are minimal. We know that her life would become a disaster if Thomas made public the pictures in the park. “Nothing like a little disaster to shake things up” replies Thomas with the cheek of someone very young who has never known disaster. She’s involved in a narrative that is fundamentally closed to us and which we catch only in the glimpses that Thomas sees. We can only infer that the situation is serious from her nervous pacing, the fact that she attacks Thomas in a futile attempt to get his camera, the fact that she finds where he lives by some means that she refuses to reveal, and that she is somehow involved in the ransacking of his studio to take the pictures by force. The last time that we see her, significantly from his point-of-view, she seems to literally disappear into a small crowd of pedestrians casually strolling on a London Summer evening in 1966. Thomas also vanishes in the final moment of the film via a movie trick pioneered by Georges Melies: the jump cut that makes objects appear and disappear. Antonioni is making us aware at the end that Thomas himself is an image, a fiction, and it is appropriate that he disappears into the vast empty field of the park, a green mass that at the end becomes like the flat space of a painting.

Blow-Up's final shot before Thomas disappears. The flat space of a painting.

Blow-Up the sign "which seems to say nothing but simply registers its presence as a true sign..."

All of the principal characters in the narrative vanish in the course of the film: the murder victim, the mystery woman and Thomas and the narrative can be seen as a trace or a glimpse of their brief meeting before disappearing. This lends Blow-Up an aspect of the occult mystery that seems to lie just below the shiny surface of the film. This is articulated by David Alan Mellor: “It might be plausible to imagine that despite being an agent of modernization, Thomas may have stumbled across an ancient remnant within contemporary London, coming into contact with a parallel universe, a re-performance of a ritual episode from the Golden Bough, like the juxtapositions of temporal and spatial layers in The Waste Land – the leading of the patriarch to his death in a sacred grove”.[32] The death of the patriarch or the father in The Golden Bough does not, as in Oedipus Rex or Hamlet, signal the end of civilization or empire but rather describes a ritual of pagan regeneration, a new beginning, that a culture can often perform without being fully cognizant of its meaning or its implications. There is a scene that would substantiate Mr. Mellor’s thesis beautifully described by Hubert Meeker: “When Thomas returns to look for evidence of murder Antonioni treats his repeated climb up the long steps into the park with the feeling of a pilgrimage, the labor of a quest, his progress through the night lighted by the neon gleam of a large sign, which seems to say nothing but simply registers its presence as a true sign, a primitive emblem casting its light on this natural preserve and the vulgar cadaver that it contains.”[33]

GO AGAINST THE BEAT

Thomas’ hapless pursuit of the mystery woman lands him by chance at the Ricky Tick Club – a well known venue that showcased local bands such as The Rolling Stones who were regulars in the mid sixties. Antonioni carefully recreated the club in Elstree Studios outside of London in order to be able to shoot unimpeded by the many small rooms (in the real club) lined with black paper. More than one person involved in the making of the film, including the guitarist Jimmy Page, made the observation that when the Yardbirds played in clubs people danced ecstatically like mad for hours whereas Antonioni famously had his club goers listening to the music in a coma like state of inertia looking on blandly a during a magnificent concert by The Yardbirds performing Stroll On, a remake of an earlier Yardbirds hit Train Kept A-Rollin’, from their Having a Rave Up album released in 1965. The audience come to life only after Jeff Beck breaks his guitar and throws the neck of the guitar into the audience creating pandemonium as everyone scrambles for it. Thomas fights for the prize, seemingly for the pleasure of it, and ends up with it scrambling away into the night. The moment he sees that no one is after him he discards the guitar bits and moves on while a young couple is standing nearby; the man examines the guitar neck and discards it as trash. This is one of the few occasions where Antonioni indulges in direct symbolism and for that reason the moment seems strangely incongruent with the rest of the film.

Blow-Up The Yardbirds

Blow-Up Jimmy Page

The zombified club members who audience occasionally look at the camera with indifference seem to haunt the film in a peculiar way that is disturbing, enigmatic and psychologically powerful. What are we to make of it? This is Antonioni: “We know that under the revealed image there is another one which is more faithful to reality, and under this one there is yet another, and again another under this last one, down to the true image of that absolute, mysterious reality that nobody will ever see.”[34] The audience is in a sense expressing their inner life after the collapse of conventional religious foundations on the one hand and modernist beliefs in progress and technology on the other. The audience is left empty of all conventional meaning or direction dancing by themselves and staring off into an indeterminate space and occasionally at the camera. But in listening to this music and in seeing the reactions to it we also sense that the audience is creating a new sensibility and a new approach to life that they themselves cannot yet fully articulate because it is too new. Antonioni’s camera manages to catch this new awareness in slow fluid traveling shots that - as Thomas says earlier to the mystery woman - “go against the beat.”

CUBISM IN EXISTENTIAL CRISIS