Gone to Hollywood: Annie Leibovitz and Helmut Newton Shoot the Stars

Published in the catalog Greetings From LA: 24 Frames and Fifty Years 2016

The medium of photography always raises the question of the relationship between seeing and knowing.

Ulrich Baer – Spectral Evidence: The Photography of Trauma

The most exact drawing may actually tell us more about the model, but despite the promptings of our critical intelligence it will never have the irrational power of the photograph to bear away our belief.

Andre Bazin – The Ontology of the Photographic Image

Vanity Fair 2006 Annie Leibovitz

In Annie Leibovitz’s re-constitution of the neoclassical European tableau in 2006 for Vanity Fair magazine sexual stereotypes that one would have hoped had quietly passed on find new life in a display of designer underwear. The fact that Leibovitz’s picture pays direct homage to Hollywood, as she has done repeatedly for the same magazine, with its massive artificial lights (the inadequate sun and moon have been replaced by Klieg lights) is perhaps an unconscious celebration of the Futurist’s worship of technology – and disgust with nature - without giving much thought to where this technology, and that disgust, might lead. Norman Mailer told us in his book on the moon landing but no one has much time for that now.[1]

In the earlier part of the 20th century the Italian Futurists had a profound faith in technology, and its presumably inherent ability to liberate man from his over civilized state, and from "nature." In their manifestos and tracts - written by their spokesman Filippo Marinetti, they saw their artwork partially as a call to arms for a new man to emancipate himself from the decrepitude of smug professors and enter into a state of pure, exalted feelin, or spirit. They excluded women as a matter of course since they considered them a part of “nature” - in effect a separate subspecies. The Nazis, who rejected almost all European avant-garde art as decadent, grotesque and immoral made an exception for the Futurists, as both Fascists and Futurists were united in a worship of neoclassicism - typified by Leni Riefenstahl's fascist films and Albert Speer's monumental plans for a "New Berlin” - built on a massive pseudo Greek/Roman plan that would dwarf Washington, Rome and Paris.

Nastassia Kinski and James Toback Helmut Newton

Hollywood films over the years co-opted the Futurist faith in speed, anti-intellectual aggression, misogyny, war, and technophilia as good things. But from a business/profit perspective, they wisely left out the manifestos that detailed the Futurist political agenda, which flirted openly with racism, antisemitism and fascism. A sample of Marinetti's style: "We intend to sing the love of danger, the habit of energy and fearlessness. We will destroy the museums, libraries, academies of every kind, will fight moralism, feminism, every opportunistic or utilitarian cowardice. We will glorify war—the world’s only hygiene—militarism, patriotism, the destructive gesture of freedom-bringers, beautiful ideas worth dying for, and scorn for woman." Many people took them to be inept clowns with an attitude but in many ways it would prove to be their century - while Marinetti's naive, disgusting and misogynist prose was written (for Le Figaro) in 1909 he clearly had a good grasp on what was coming - one that put many academics and historians of the time to shame. The Futurists' had a full and profound faith in technology as a force that would come to subdue nature, control it, and perhaps ultimately supplant it - technology was also a means to reach the sublime, as nature would now play second fiddle to man's heroic, fantastic machines. Werner Herzog, in his brilliant film Signs of Life (1968) beautifully ridiculed this idea when some German soldiers during WWII, stranded in a desert, with no news and no direction home, go insane and decide to build a machine that produces a light that is brighter than the sun. Alas Herzog's warning was not heeded, and in the new millennium technology as a means to experience the sublime is an accepted, mainstream, concept that few would question.

But it would not be up to Marinetti to lead the charge in Italy but to a fan of his writing, who was also a published writer and journalist: Benito Mussolini, head of the National Fascist Party. Over half a century after the Italian Futurist's self-destructive rants, Paul Virilio, the brilliant French cultural critic, wrote that: “Filippo Marinetti “metaphorizes (sic) about the armored car: the overman is over-grafted, an inhuman type reduced to a driving and thus deciding principle, an animal body that disappears in the superpower of a metallic body able to annihilate time and space through it’s dynamic performances.”[2] A better definition of Hollywood films and the power of the star system would be hard to find but Virilio is describing war and Marinetti's love for it.

The Shanghai Express 1932 Hollywood baroque spectacle at its most sublime and absurd in Josef von Sternberg's classic film.

From its beginnings European transplants to Hollywood like Josef Von Sternberg made analogies between film sets and war[3] but unlike most aspirants to Hollywood glory he was fortunate in being able to translate his baroque sense of spectacle into stunning set pieces such as The Shanghai Express (1932) for Marlene Dietrich and Anna May Wong. The ‘Shanghai express’ was in fact situated in a railroad depot in San Bernardino, a sleepy suburb of Los Angeles, located in the heart of the Inland Empire. Von Sternberg eventually retired from these highly stylized, poetic melodramas to his house in the Hollywood hills, designed by the Austrian Richard Neutra, to collect German Expressionist art and fine wine.[4]

Leibovitz’s Vanity Fair photograph from 2006 pays homage to classic Hollywood films about the industry itself such as Singing in the Rain (1952) while simultaneously referencing French Romantic painter Theodore Gericault’s The Raft of the Medusa (1819). With the careful deliberation of a French neoclassical painter working on a commission from the state Leibovitz calibrates and manicures every action and gesture for its effect. Her models illustrate current tastes in beauty but seen through the prism of George Hurrell and Ruth Harriet Louise, two very successful photographers who pioneered these kinds of grandiose tableaus for Vogue magazine, via Hollywood glamour portraiture, that defined “the dream factory,” in the early 20th century. This was an aesthetic that perfectly mirrored the clean, energetic lines favored by Futurist aesthetics, and artists such as Tamara de Lampicka, who subsequently popularized the style in her illustrations and paintings. The theatrically designed set with a fake sky is self consciously artificial and the placement of the individuals within the frame is banal. Leibovitz lacks Helmut Newton’s sense of improvisation with an actual space, dark humor and intense feeling for the urgency of everyday life – of time passing – and what the world is really like in all its absurd contingencies. We see an example of Newton’s themes as they play out in his work in his homage to Hollywood that first appeared in Playboy magazine in May 1983.[5]

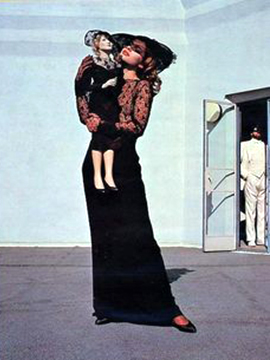

Nastassia Kinski and James Toback Hewlmut Newton

In Newton’s photographs the seductive images of wealth and power are in the form of a house in Los Angeles with a pool surrounded by thick vines. Unlike Leibovitz’s large format camera that eliminates grain, or the effects of the medium, Newton opts for 35mm and 2¼ cameras, employing an apparently casual snapshot aesthetic. What Leibovitz and Newton share, aside from an encyclopedic sense of art history, is a taste for luxury goods. Nastassja Kinski lounges with the director James Toback whose reflection in the pool is beautifully caught in a vice between his real self and Ms. Kinski whose reflected counterpart is a traumatized doll. Perhaps this is some remnant from Fritz Lang’s Weimar period via Hans Bellmer and Hans-Jürgen Syberberg’s Our Hitler (1977). Newton’s playful facility with composition is fully operational as the doll lies poolside along with an overly made up and over-dressed Ms. Kinski whose pedigree is called into action as she is made to mimic the German stars before her that came to California to be in movies.

But something is wrong. Ms. Kinski’s stiff body looks like she’s on an operating table, and the incongruous black frilly clothing, for a night on the town, is worn in the harsh midday desert light of Los Angeles. The lounging director’s more appropriate white linen suit, white buck shoes and dark glasses make the discordant incompatibility more glaring. The conflicting wardrobes between the man and the woman, night and day and black and white (like the movies of Hollywood’s past) are carefully measured by Newton to express irreconcilable differences. When Ms. Kinski grabs the back of Toback’s head as he kneels before her, he is caught between the doll and her exposed breasts, seemingly not sure what to do, or who or what to worship.

Sunset Boulevard Billy Wilder The voice over narrator explains his own death as we see him float in the luxurious Hollywood pool.

The pool and the acrid light calls to mind Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard (1950) in which a dead man narrates his own story, in a sense writing his own obituary, a Hollywood pastime that is savagely dissected by Wilder and Charles Brackett. That unrelenting summer sunlight seems always to signal in Newton’s work a vacation scenario. The parents are gone – it’s time to party. The result should be silliness and fun but architectural sumptuousness and excess wealth seem to turn all the fun into regimented vice, and the play (or is it an opera?) becomes a melancholic formula for pleasure that is both comic and profoundly removed from actual emotional connections. The doll makes that explicit in these pictures but it is to be seen throughout Newton’s work. It’s a failure to connect. The sadomasochistic narratives, so often at play in Newton’s photography seem to be the opposite of decadent or depraved. Rather it all seems to be seen from the point of view of a child or an adolescent playacting. Newton’s models often seem like children who understand that at any moment the adults will come back home and put a stop to all this foolish playing around. The erotic transgressions seem to be entertained rather than earnestly experienced. In another sense Newton is very much a sophisticated European adult: the tight formal framing and beautifully composed mise-en-scène in his work is always complex, witty and sarcastic. Eros and Thanatos play out their parts in the staged tableaus with the same sense of tragic clarity as Ingmar Bergman, but with the added sardonic wit of Ernst Lubitsch, all combined with a seemingly casual effortlessness.

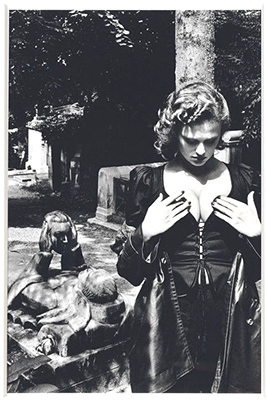

RIve Gauche 1978 Helmut Newton

How do these qualities manifest themselves on the page? Newton referred to himself as a “gun for hire”.[6] This often consisted of shooting the new wardrobes for fashion houses. In Rive Gauche 1978 shot for Saint Laurent’s ready-to-wear line, Newton playfully breaks one of the cardinal rules of photography. While trees or posts are never to be placed directly behind a subject’s head Newton places one dead center behind the models’ perfectly coiffed hair. This turns her into a sculptural element, or a ship’s figurehead, suspended visually by the strong vertical. The model touches her breasts while looking down at them not in a playful way but looking very serious, as if now conscious of the fleetingness of their beauty. Behind her is a horizontal sculpture serving as a sepulcher over a grave that holds in its hands its own death mask – a memento-mori with a sense of irony. Newton ups the stakes in the game by including a woman in a street of graves who is herself grave but also very much in the flush of youth. Is that a dress or a costume from another time? Is the woman dead? These are questions that one normally applies to works of fiction. Newton has taken us there with a beautiful sense of theater, in contrast to the hyperbolic theatricality of later imitators such as David Lachapelle. In Newton’s picture we can spend time in subtleties such as the beautiful, natural speckled light from the nearby trees as they play off the hard edges of the Gothic shadows on the graves. The two heads, of the woman and the death mask, female and male, soft and hard, alive and dead also play off each other operatically, as if they were singing an aria to each other. This is a musical story that is very grown up, dark and funny. You have to be an adult to hear it otherwise the image is silent. While the Vanity Fair image by Leibovitz is as clear and as unambiguous as an advertising for cereal, Newton delights in a formidable visual density that is dark, mysterious, where the narrative lines are not always clear or easily understood. The depth of ambiguity frustrates narrative expectations, that he himself has deployed, as he juggles those emotionally loaded narrative lines.

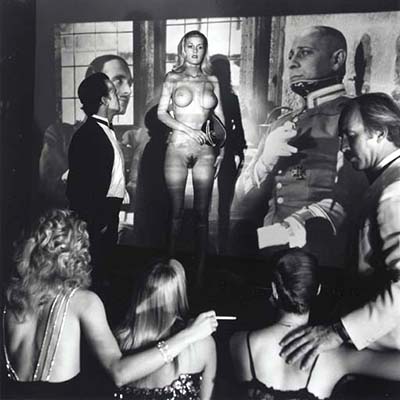

Playboy Mansion Projection Room 1986 Helmut Newton

At times the infusion of cinematic narrative is blatant as when he photographs a projection, at the Playboy Mansion in Los Angeles in 1986, of Eric Von Stroheim in Jean Renoir’s Grand Illusion (1937) onto naked models staging an ambiguous S/M tableau. The first response to the image is a disturbing sense that these narratives have reached a stage of mannered self-consciousness creating a visual endgame of sorts. The baroque imagery is vertiginous. The lurid decadence is something that is observed but Newton does not elucidate or editorialize. He is content to regard the excessive staging, the tableaus influenced by Weimar culture and avant-garde photographic superimpositions - it's all seen from a distance and kept at arm's length - he seems happy to participate as an observer clicking away. This voyeuristic aspect is a central theme that runs through all of Newton’s work, and he often treats it with great humor. Newton always emphasizes that aspect of his personality - the dissolute tourist, the amused, overripe voyeur, who observes the strange customs of the locals, and then, before any emotional involvement or uncomfortable adult seriousness descends, moves on to the next thing with a mercenary nonchalance.

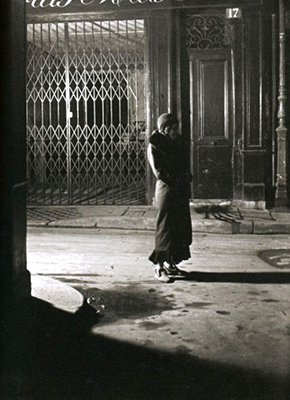

The sense of mortality that is ever present in Newton’s work is palpable and brutally direct. He never flinched from death when he had his camera with him. In this he had much in common with Lisette Model, Weegee and other artists who were attracted and repelled by mortality and decadence as a subject. Another photographer that he might be usefully compared to is Brassai, who was also fascinated by sensuality and death as they manifested themselves in urban settings, in scenes that seemed both staged and spontaneous, repellent and seductive. The indoor lighting in Brassai is always a harsh light where everything is either over-lit or in complete darkness. In Brassai’s exteriors we see long shadows cast at night from the astringent lights of the city that go into infinity collected in the classic book Brassai: Paris de Nuit published in 1932. Much later in 1976 the follow-up volume was published that collected the images from the same period, of brothels and transvestite clubs, showing full frontal nudity in Le Paris Secret des Annees 30.

Paris de Nuit Brassai

In these nighttime images Newton learned lessons that would last him the rest of his life. In both Brassai and Newton there are always questions that remain unanswered, there is openness and secrecy, tenderness and amorality. But perhaps what is most striking is the casual and brutal hardness that we sense comes from the street, and always those unforgettable, resilient, looks into the camera that don’t back down. After Brassai we would have to wait until the work of Diane Arbus, John Deakin, and Vivian Maier to see the world again, in black and white, with that kind of hard clarity, candor, and dark humor.

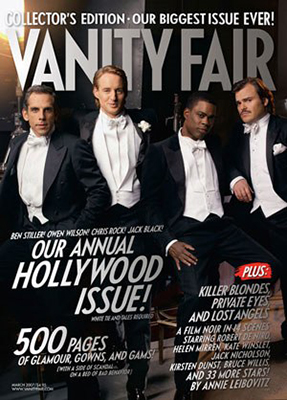

In Leibovitz’s cover for Vanity Fair March 2007 depicting men in expensive clothes the heavy hand of the art director lets us know we are in the land of power and money and that we need to respect the players on set because they own the bank. We are in the world of The Great Gatsby, but without the ironic undertow found in Scott Fitzgerald’s book that, at the last moment, pulls the rug out from under the class pretensions to reveal the brutal, horribly mundane reality underneath. Quite the contrary, in the Vanity Fair photograph the polite sycophantic applause is almost audible. The fear that would solicit such a response brings us back to the war scenario we saw outlined by Virilio’s text because in war you must also be very careful as you can lose everything by uttering one wrong word, or by never finding the right one.

Vanity Fair March 2006 Annie Leibovitz

One thinks of Orson Welles in the seventies - still young and vigorous by our standards as in 1975 he had just turned 60 - often seen in Ma Maison, an exclusive restaurant on Melrose Ave. in West Hollywood. It is here where Welles received mail and made phone calls, treating the French birthplace of “California nouvelle cuisine” as an office. The nondescript restaurant was in the basin of LA just down from the famous hills where the rich and the powerful read screenplays poolside and gave the thumbs up or down like the royalty of empires past. Welles would invariably be waiting for a producer, trying to find the magic words that would bring back Xanadu! What must have gone through his mind as he sat there, twirling his enormous cigar in the restaurants Astroturf-lined patio, staring at the blinding light he had first seen on coming out to Los Angeles in 1940, courtesy of RKO Pictures, to make an adaptation of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness?[7]

A March 2008 Vanity Fair cover shows actresses assembled in a photo studio lit and dressed in such a manner as to suggest the palette of European aristocratic portraiture as practiced by Francois Boucher. The photograph is a shallow and narcissistic display of power that would be appropriate for an annual report if Hollywood were thought of as what it actually is: a corporation, or more exactly a series of corporate entities, with various interlocking interests. The image evokes aristocratic classicism for the obvious reason that we are looking at a photograph of contemporary royalty - there appears to be a simple one to one relationship that is meant to be as clear-cut as a row of diamonds in a display case. But there are problems with this idea because the image is more complex. The actresses are clearly in-the-know, they are playing a game with the iconic images from the past of Jean Harlow, Carole Lombard and others. They also seem like they might be conscious of the shallowness and artifice that constitutes a cover of Vanity Fair while clearly relishing the massive exposure and the clever concept. Everyone concerned, including Leibovitz herself, seems aware that it’s ephemeral. But that very disposability, surely, is just a part of the business, the industry, the publicity machine. Hey - it’s Hollywood.

Vanity Fair March 2008 Annie Leibovitz

Pop art’s famous celebration/critique dualism, that we see most beautifully articulated in Andy Warhol’s portraits, is standing by in the wings but it doesn’t quite fit here. Leibovitz lacks Warhol’s profound sense of unease and religious angst that underlie his profound response to contemporary idolatry. Warhol was a strict Catholic and, from that perspective, knew the difference between a want-to-be Icon and the real thing. In Warhol our modern stars, be it Marilyn or Mao, were always overfull and empty at the same time and this created a tension from which there was only one escape: humor. The playfulness in Warhol is always tinged with a profound sense of melancholy at the void sitting just behind the contemporary idols of our time – the beautiful glittering facades that are as thin - and fleeting - as paper money.

In the Vanity Fair photographs the images are reduced to advertising, that is, communication in the service of marketing. It is a world of lawyers, publicity departments and agents and their films show it in every frame. The Vanity Fair cover expresses that reality as a fait accompli. Yet the bland artificiality of Leibovitz’s image generates associations that one has to admit are cinematic – one thinks of Douglas Sirk and the brilliant artificiality of Written in the Wind (1956). Sirk’s narrative is pure melodrama but his faith in those images is moving and solid. In the Vanity Fair picture faith is replaced by bemusement at the power of artifice itself to service the glow of the surface and the pleasures to presumably be found there.

Interestingly both artists use 19th century neoclassical conventions but to different ends. For Leibovitz the image is always bound to those aesthetic ideas that insist upon order, stability, clarity, balance and carefully selected hierarchical sets that make up a coherent whole. In Newton’s work those neoclassical conventions are turned on their head with a glee that Luis Buñuel would have understood perfectly as he managed to do the same repeatedly in his work, most spectacularly in Viridiana (1961) - where we see a wicked redeployment of Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper. In Newton’s pictures his hierarchies within a composition are often preposterously absurd treating the whole idea of hierarchies as a joke, and calling attention to the neo-fascist underpinnings of those fantasies predicated on control, fear and violence. The balance and stability in his images is achieved with props that make a mockery of stability and balance, relating them to ceremonial fantasy scenarios and kitsch. The high degree of order in Newton is often quite elaborate, fetishistic, baroque, calling attention to itself, but this order is only there as a hors d’oeuvre before the main course arrives – the intensely disorderly sex that Newton’s narratives always suggest with such a wonderfully louche directness. Leibovitz’s and Newton’s work both partake of neoclassicism, and of the allure of Hollywood celebrity, and the power games that come along as baggage, but to opposite ends.

While Leibovitz plays with role playing in the Vanity Fair covers, Newton digs a little deeper in the poolside images of actress and director squaring off, and suggests the contingencies and power games inherent in such a meeting and the mediation of photographic conventions at play (in every sense). One senses the historical weight on Ms. Kinski stretching back to Greta Garbo and then closer to home: Wim Wenders’ The Wrong Move with Rudiger Vogler and later with Harry Dean Stanton in Paris Texas; the German femme fatale in Torrents of Spring from the novel by Turgenev; a circus performer straight out of Picasso via Marcel Carné' in Francis Coppola’s One From the Heart. Newton’s pictures can speak about Hollywood in a way that is complex and that the “dream factory” itself has been for the most part reluctant to investigate despite the fact that films about filmmaking are a genre into themselves.

Nastassia Kinsky & James Toback Helmut Newton

Los Angeles is loaded down with histories as so many different Hollywood’s have passed through the city and left their mark. Not just the stars but the extras and technicians, the people just surviving on the edges of the city. You can still see the traces of their lives in Hollywood, Echo Park, Atwater and other neighborhoods with small dark Spanish bungalow apartments made of beige stucco with little lawns of manicured grass and occasional desert plants. The works that the film industry produces about its own history are invariably conventional morality tales that are, to say the least, cynical in their approach. It goes with the territory but there are always exceptions, where the open wounds are allowed to come to the surface, such as Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard, Nicholas Ray’s In a Lonely Place, and David Lynch’s LA Trilogy: Lost Highway/Mulholland Drive/Inland Empire.

Newton’s poolside images carry a historical baggage with them that is intensely felt even if that intensity shows up as a sardonic grin. For Newton the pleasures are always mediated by second thoughts. Newton remembers things. Is it his parents in the war who were both killed in the Holocaust? Perhaps it's being taken as a child to Australia where he would grow up into manhood and learn to become a "gun for hire?" Maybe it's the last place that he saw in Berlin before his long journey to another continent - the old train station at the Zoologischer Garten? Or perhaps it's the local dances, for young people to meet and mingle, in Shepparton on Saturday nights?[8] Those things are in his pictures but not, as we might expect, as either a cry of despair or nostalgia - they are simply a subtext to beauty, pleasure and aesthetic play and act as a counterpoint to them.

Back in LA in a land of harsh lights – real and artificial - where the players who make the films call their enterprise “The Industry” (and call themselves “players”), it is primarily those second thoughts that are the key to Newton’s photographs and that make them work on so many levels at once, allowing them to transcend the practical and facile categories of erotic photography, celebrity portraiture or fashion for which they were intended. Now they stand on their own – no Hollywood ending is necessary.

[1] Of a Fire on the MoonNorman Mailer Little, Brown 1970

[2] The Aesthetics of Disappearance – Paul VirilioSemiotext 2009

[3] Fun in a Chinese Laundry: an Autobiography – Josef Von SternbergMacmillan 1965

[4] Ibid3

[5] Playboy Helmut NewtonChronicle Books 2005

[6] Gun for Hire Helmut Newton, June Newton Taschen 2005

[7] The Making of Citizen Kane – Robert L. CarringerUniversity of California Press 1985

[8] Helmut Newton Autobiography – Helmut NewtonDoubleday 2003