The Delight of the Particular: The Photography of Ronald Traeger

“The boundary between the end of childhood and the beginnings, however rudimentary, of adult life, is vague.”

“Nobody can commit photography alone.”

Ronald Traeger, Rome Series, 1962 The hard left and the hard right - politically and pictorially - meet a policeman with a dramatic white glove that signals something dramatic but ambiguous.

The pictures were, for the most part, meant to be seen in fashion magazines and the connotation is that this is a programmatic, institutional activity - the codes inherent to fashion images are, for the most part, ubiquitous and disposable. As we know its major functions are to give pleasure, to amuse, to educate, to create material needs, to reassure, and to help us conform. Yet within this rigid commercial matrix there is room for ideas to come into play, which is why a fashion picture by David LaChapelle looks very different from one by Wolfgang Tillmans. As Roland Barthes said in The Photographic Message "...every code is both arbitrary and rational; all recourse to a code is therefore a way for humanity to prove itself, to test itself through a rationality and a liberty."(1) It is in that space of play before the image congeals into codes that photographers are relatively free. This essay explores the work of one such photographer who worked briefly from 1962 to 1967.

Ronald Traeger's pictures are dramatic and quotidian, ambiguous and matter-of-fact, playful and philosophical. The pictures seem to participate in a holistic sense with the people and the spaces that he photographs and this world-view is not so much illustrated as made concrete in the work itself. They express a philosophy of life and tell us about the world Traeger saw: a fragmentary space in continuous flux that we can perceive only by being a part of that flux; perception requires us to be a participant. This phenomenology is made tangible in the present tense as a form of play. Of course these kinds of juxtapositions of extreme differences that Traeger employed were seen before in pictures, such as those by Louis Faurer, Diane Arbus, Saul Leiter or Robert Frank. But in their work these urban fragments were often perceived to express estrangement and displacement. Even contemporary photographers such as Anne Eickenberg or Nick Waplington work along similar lines as those set by the New York School – that is they are primarily about chance encounters, alienation and the absurd. With Traeger on the contrary these paradoxes are perceived pleasurably - even ecstatically - not as a withdrawal from the world but as a way back into it. The humanism is genuine because it is articulated in the way the pictures are composed, rather than imposed or illustrated. How did Traeger accomplish this balancing act between play and philosophy, between the decisive moment and the any-instant-whatever?

The work of many young photographers in the world of fashion, fine art and advertising now look like the kind of self-conscious, ironic, artificial tableaus that Traeger and his colleagues so carefully avoided, even at a cost to their commercial careers. It is those slick, turgid postwar tableaus of Norman Parkinson, Clifford Coffin and Cecil Beaton, among many others, that the younger photographers sought to overcome, and perhaps to overthrow. There was a need to transcend that icy, affected artificiality and get at something tangible and real - something alive, factual, spiritual and bluntly corporeal - it was in the air. The Beat Generation writers felt it as did the younger composers of pop music who wanted to eradicate the artifice of sentimental conventions and get at that essential thing, but what was that thing, and how did one get to it using photography or words or music? These were the primary questions of the young artists coming into their own during that crucial transition period, from the late 1950's to the early 1960's, as they looked around at the world they were in: Post-War, post-Hiroshima, post-Gutenberg, post Abstract Expressionism, post Steichen's "Family-of-Man," and in the midst of an electronic revolution of which television was merely the tip of the iceberg. How did Traeger's pictures come about, what was he trying to do with them, what was the social context in which they were created, and what makes them so contemporary?

Ronald Traeger, Rome Series, 1962

Before London there was France and Rome and before that Los Angeles. Trained at the Art Center College in Pasadena, California, Traeger, along with four friends founded the Globecombers, a group whose reason for being was – explicit in the name – to get out of LA as quickly as possible. The school lacked inspiration, and like most art schools then and now was reliant on rules, traditions and an unspoken submission to certain conventions. The Art Center in particular was known for a highly standardized commercial track that sought to place photographers within a viable existing market. While that is certainly a worthy aspiration, more adventurous souls might feel trapped - hence the Globecombers. After a year Traeger, and his friends set sail for Europe, where his life would be transformed. After a few months in Rome and Paris, where he worked briefly for Elle Magazine, he eventually settled in London, where he met his future wife Tessa Grimshaw. Unlike his contemporaries who had very long careers Traeger died tragically of Hodgkins disease in 1968 at the age of 32. His wife, who wrote a biography of this period and their time together in Europe, survives him, and she, along with Martin Harrison, published a book about his work in 1999.

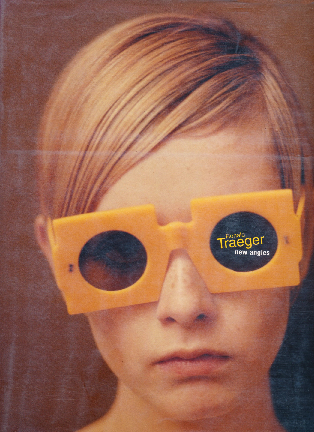

Book Cover: Ronald Traeger: New Angles, Schirmer/Mosel 1999

Martin Harrison: “Although assignments occasionally came their way…they (the Globecombers) mostly photographed speculatively in the hope of their work being syndicated…the photographs that Traeger made in 1962 of the changing influence of Church and State in Rome evolved into an important body of work, his first mature achievement. The series was completed in four months of intense activity…”(2) Traeger was twenty-five. A short time later he would move to Paris and try and make a go of it, getting some assignments for portrait and fashion work at Elle. Eventually he would settle in London where he worked regularly for Vogue alongside the photographers of his own generation. David Bailey, Terence Donovan and Brian Duffy formed the “terrible trinity,” a term coined by the press of the time.(3) The young photographers were also called “East-Enders” which was a phrase that not only described a district in London but signified the working class - an important distinction in still parochial Great Britain. While previous generations of British photographers, most famously Cecil Beaton, had come from the upper classes, and were featured regularly in traditional journals such as Picture Post and Life, the “terrible trinity” wore their working class origins on their sleeve. A brief window of opportunity had opened in the rigid class system in England that was also happening in art, film, literature, theater and music. Aside from the brilliant self promotional “terrible trinity” there were other photographers of the time, young and older, who jumped head first into this new revolutionary period, such as Penny Tweedy, John Cowan, Michael Cooper and John Deakin.

These photographers were part of a larger cultural revolution that was worldwide in its scope and that in Post-War England included the Angry Young Men that rejected the staid mannerisms of the English theater and brought a stark realism to their plays that actually depicted how people actually spoke, and just as importantly how they were silent. The Kitchen Sink and the Free Cinema movement in England were part of a wide ranging series of "new-waves" from France to Brazil that completely revolutionized how films were made and directly challenged the status quo of Hollywood, and what François Truffaut called - with his then characteristic youthful sarcasm - “le cinema de papa” and "the cinema of quality." There was a whole new approach from the postwar era as the new Pop Art paintings dealt with everyday life and popular culture in a much more brutally direct, acrimonious, mocking approach acknowledging the broad range of image repertoire in the world at large - a repertoire that was by Richard Hamilton’s admission, primarily photographic. Aside from Hamilton we see this in art works by Derek Boshier, Pauline Boty, Malcolm Morley, Peter Blake and Eduardo Paolozzi, who was making pop art collages as early as the late 1940's, and who founded The Independent Group in 1952.

There was also the studio work of pop groups that would revolutionize and reinvent contemporary music - most famously The Beatles - leaving the formulaic, prefabricated pop created by impresarios, such as those in the Brill Building in New York, far behind. The staid, pedantic, formalism of contemporary classical music retreated to academia, where it resides today (with a shroud of text in place of a tomb). American jazz completely revolutionized post-war American music, taking up the mantle of pre-war European classical music and incorporating African polyrhythms and modal experimentations. What was happening in the arts, jazz and pop music was, in fact, taking place in all areas of the arts and humanities bringing down social barriers that the ruling classes had considered sacred markers. Of course the institutions that were, in effect, there to protect, uphold, and advance the primary beliefs and ideologies of the ruling class, fought back - but for a brief time a window of opportunity was open - and a fortunate few made it through to the other side. What did they find once they were on this “other side?”

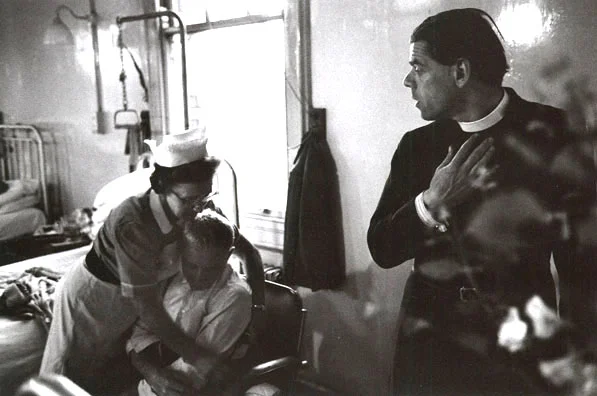

Ian Barry, A Mission's Failure 1963 for the London Times A missionary ready to perform good deeds fails horribly in the care facility for the poor in South London. Berry's confrontational approach is direct and uncompromising.

As to be expected there would be a push back against these new, often radical ideas, that would develop over the following decades. In the sixties these young photographers took on portraiture, journalism and fashion and because of their youth and quick rise to prominence came to be known as “The Young Meteors”.[4] This group consisted of people as different as Don McCullin and David Bailey, Nigel Henderson and Penny Tweedie, one of the few women photographers then working and showing regularly. Despite their differences, they all shared a similar aesthetic concern with everyday life that was depicted in a way that seemed unaffected by formal or flâneur strategies that, while not completely absent, remained in the background leaving center stage to a content that was often harshly realistic and enigmatic, with all of the inconsistencies and rough edges left in place, and without a clear narrative arc that explained the action. What was then highly unusual, and now unthinkable, was that this body of work was disseminated to the public at large via the popular magazines of the period, including the influential Sunday London Times Magazine, on a regular weekly basis.

The approach that the young British photojournalists in the 1960’s took was blunt and confrontational with both their subjects and their viewers. They were fearless and relentless and the resulting images were often brilliant, direct and profoundly disturbing. A good example is Ian Berry's A Mission's Failure, 1963 for the London Times. Berry depicts a young missionary sent to a care facility in South London, and his disastrous confrontation with men who were angry, fatigued and who saw the priest as an authority figure that they could finally lash out at. Berry's intense image captures both the violence of the scene, the older man’s helpless frustration and the young priest's shock and uncertainty as to how to proceed. The Young Meteors were able to express the moral ambiguities, mysterious narratives that lead nowhere, and dramatic/comical collisions of cultures and classes into a poetics of urban space without resorting either to cloying narrative clues or to annoying painterly references common to Pictorialism. Their often highly ambiguous and cryptic photographs were, paradoxically, as direct and forthright as a snapshot, an aesthetic that was wholeheartedly embraced. This push/pull between the recondite and the matter-of-fact occupying the same space was the engine that drove the work of Traeger and The Young Meteors.

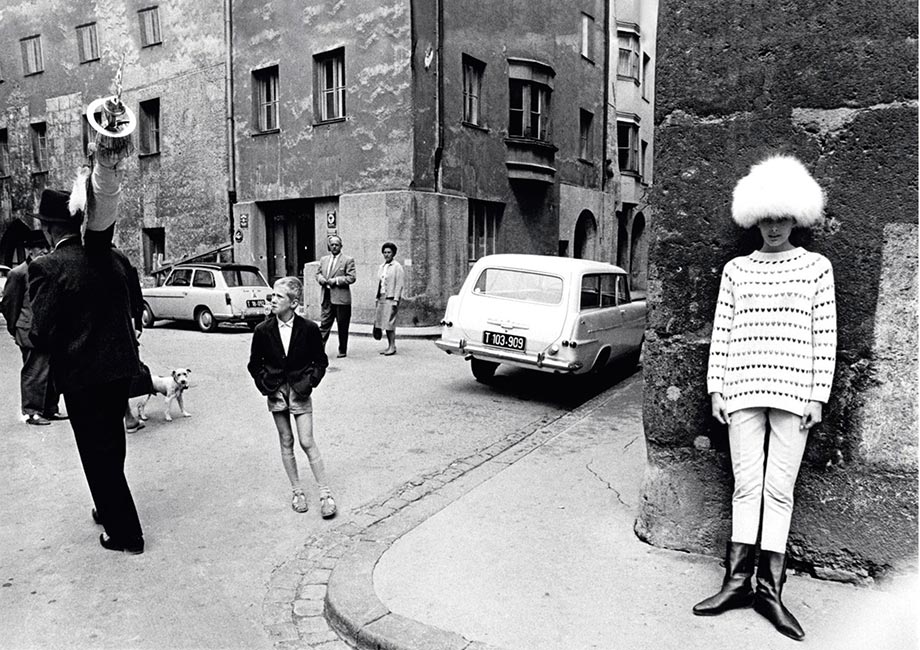

Ronald Traeger, Model Tamara Nyman, Vogue 1963 Documentary realism and fashion share the same stage and the principal player is no longer the model, who now shares the space with a young boy indifferent to her dramatic outfit. The delicate geometry of the space and its local inhabitants beautifully play off the model as in musical counterpoint.

Traeger’s use of the snapshot aesthetic is beautifully articulated in Model Tamara Nyman, Vogue 1963 as realism and fashion share the same stage and the principal player is no longer the model but the interaction of the players within the frame. The image shows one of the many off center squares in Europe with Ms. Nyman on the far right leaning against a very old wall that contrasts nicely with her youth, in a matter of fact way, arms at her sides like a kid. On the left an older man dressed in black with a top hat for some special occasion carries a long ceremonial object that looks like an enormous trophy. Near the center a boy of about twelve looks at the man in black with a very serious air that reminds us that the end of World War II was only 18 years in the past. The left side of the frame is beautifully composed in a traditional manner, and could easily be a Henri Cartier-Bresson from his 1930's period, but the model on the right smiling contently creates an extraordinary sense of play - of fiction entering the scene and creating a sense of stagecraft. The delicate geometry of the space and its local inhabitants beautifully play off the model, as in musical counterpoint.

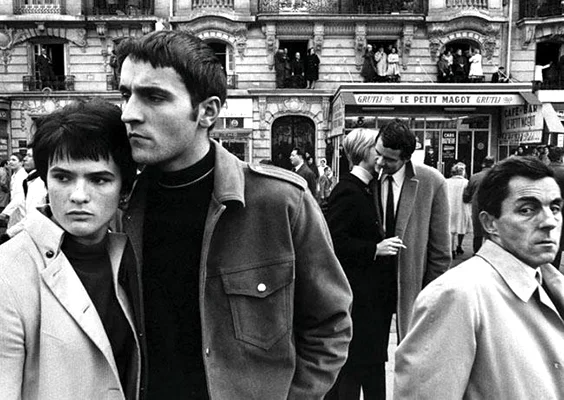

Ronald Traeger, Paris 1962 for Elle magazine (unpublished) The model looks at someone blocked to us by random layering of adverts and text reminiscent of a cubist paper collage, while in the background a random male passerby looks on resigned, hands in pockets - the poetics of urban space was never expressed more beautifully.

Another image, from Elle magazine (unpublished) Paris 1962, shows a model sitting in an outdoor cafe, while Traeger shoots from inside through the glass window. The model looks left at someone blocked to us by a wall full of random layers of adverts and text that have been piled one on top of another over time, haphazardly creating an unintentional overlay of diagonals with fragmented text, reminiscent of a cubist paper collage. Another arbitrary element that is used pictorially is the old steam heater under the model that produces a series of vertical lines, like notes, that play off another series of narrow verticals on the window reflections on the opposite side of the frame - creating an extraordinary sense of visual counterpoint. Meanwhile in the background a lone male passerby looks on resigned, hands in pockets - like a poem by Jacques Prévert - the poetics of urban space was never expressed more beautifully.

Aside from Traeger and the Young Meteors in England there were other photographers at the time who were working with the snapshot aesthetic and exploring its possibilities, such as Gordon Parks and Helen Levitt in the United States, Agustín Jiménez in Mexico, Raymond Depardon in France and Ramon Masats in Spain, among others. There was also the influence of American post-war action painting with their emphasis on improvisation, emotional integrity, directness and speed as well as William Klein’s influential and groundbreaking book Life is Good & Good for You in New York published in Paris in 1956, and Robert Frank’s The Americans two years later. Frank worked from an improvisational, emotionally open foundation, linked more to Beat poetry and jazz than to formal European street photography, although that was also an influence. Contingent and fragmentary framing, with cryptic or digressive narrative cues were Frank’s strengths. He captured in black and white the evanescent moment beyond Cartier-Bresson’s suave, classical balance. After Frank the French master seemed somewhat affected and cautious. Helen Levitt, another member of the New York School, was also an influence. She immersed herself in a profoundly humanist relationship with her subjects - mostly on the streets of New York. Her images pivot between a casual, almost laconic, framing with highly deliberate juxtapositions, that were as formally nuanced as a ballet.

But for many it was Klein’s graphically adventurous, high contrast work that best caught the spirit of the time and place with panache and humor. Klein pioneered a radical “open frame” that, in opposition to classicism, suggested various inscrutable, conflicting and contrasting realities within the same space - some open and some closed off - some making their entrances and some their exits. The effect was revolutionary as the images suggested that it was possible to capture not only the surfaces of urban life, as had been done in the past, but the experience itself translated into an aesthetic plane of black and white. The liberal use of deep focus allowed Klein to juxtapose not only across the frame, but within the deep space created by his creative use of wide angle lenses and fast film. His use of Kodak Tri-X 600 ASA was normally associated with photojournalists who did not have the time to switch films from interior to exterior or sunny and overcast and subsequently the emphasis was on the films versatility. The price paid for this wide range of exposures was a high degree of grain. This graininess was derided at the time, at least in art photography, and seen as a sign of photojournalism, or worse, amateurishness. Klein not only accepted the grain of high-speed film but reveled in it and emphasized the grain in his printing methods by using high contrast paper and cropping to further increase the grain. Klein influenced several generations of photographers, most famously perhaps the Tokyo based Daido Moriyama who would take Klein's urban poetics and push them to the breaking point.

William Klein, Paris 1967 Klein's radical open frame seen to full effect.

Mario Giacomelli, Priests 1961-1963 Hard contrasts, idiosyncratic framing, and faces as in Neorealism.

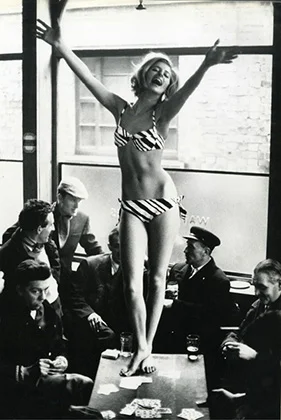

John Cowan, World's End Pub KIng's Road, Chelsea April 3, 1963 The photographer contrasts different ages and classes to incredible effect. Note that the men are all caught up in their own actions or lost in thought giving greater weight to the model's exuberant sense of play and beautiful contraposto pose - the one note that acknowledges the classical style.

Two other influences on Traeger's work in this European period are Mario Giacomelli and John Cowan. Giacomelli's high contrast black and white pictures, that virtually eliminate mid-tonal greys, were taken primarily in southern Italy where he lived. They are intense and suggestive, with a gravitas that would prove enormously influential to photographers and filmmakers. Giacomelli played with formalism, but was sympathetic to his subjects in a way that was reminiscent of Italian Neorealism, a style that was both realistic and allegorical. His cropping was idiosyncratic and judiciously fragmented suggesting both the film still and the anthropological fragment. John Cowan, based in London, was older than the Young Meteors - his studio was famously used by Michelangelo Antonioni in Blow-Up (1966). Cowan was a gifted photographer of movement and dramatic narrative action influenced by genre films. He always employed athletic models who could climb, jump, and hop over a fence. Cowan was himself influenced by Martin Munkácsi who originated this athletic style in the 1920's, but while Munkácsi favored the playgrounds of the ultra-rich, Cowan set everything in contemporary London, using the city itself - with its contrasts of class and historical styles - as a stage.

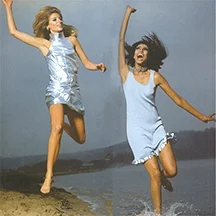

Ronald Traeger, Jill Kennington & Donyale Luna Elle magazine 1966

Traeger's London pictures would blend all of these styles and add brilliant saturated color with a sense of giddy, exuberant play. The models often mime a ritualized dance where people play with each other, mimicking the play of children but with adult bodies and an adult sexuality. The two are not separate, as in the American puritan model, wherein one leaves behind the creative play of childhood to assume adult sexuality, responsibilities and ambitions. Rather, the adult and the child are integrated into an organic conceptually coherent whole that is expressed pictorially as play, both formally, and in terms of the content. Traeger's magnificent shot of Jill Kennington (Cowan's favorite model) and Donyale Luna running on the beach is one of the great fashion shots of the period. Luna was the first African American model to feature regularly in fashion magazines, and eventually co-starred in Federico Fellini's Satyricon (1969). Her move to London was predicated on her non-marketability in the USA, due to the repercussions of widespread cancellation of subscriptions once she appeared on a six page spread in Harper's Bazaar in 1965 shot by Richard Avedon. In London she rebooted her career, working regularly for Vogue who only published her pictures in the European market. Despite her incredible otherworldly appearance - like some form of advanced human being - she was a Detroit girl and must have bonded with Traeger, as the two young Americans were on the loose in London in the decade that would culturally define the rest of the century and beyond.

What makes Jill Kennington & Donyale Luna, 1966 so uniquely Traeger's is that he has taken Cowan's ideas regarding movement within the shot, and Klein's open frame to the next level. The models are literally escaping the frame, Kennington from the top and Luna from the bottom, as if the camera frame simply could not contain them - they are captured in-media-res just before escaping altogether. This use of the space outside of the frame is cinematic and the influence of films on all of the Young Meteors is clearly evident - more so on the younger emerging talent like Traeger. The other Young Meteors, even Bailey, were still tied, however tentatively, to the traditions of portraiture established by masters like Felix Nadar in the 19th Century. It is Traeger, and the following generation who would move away from that tradition to a more contemporary cinematic approach.

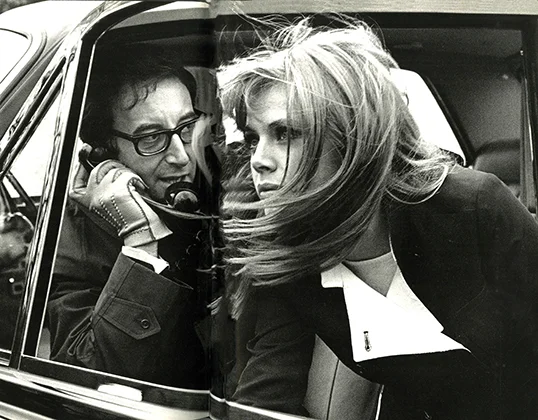

Ronald Traeger, Britt Ekland and Peter Sellers, 1967

Traeger's portraiture adopted the improvisational method, embracing the snapshot aesthetic that the Young Meteors also took on with gusto. Yet, while his work suggests the casualness and “arbitrary” framing of snapshots the pictures have a graphic sophistication in their interplay of forms, flattened by the use of a long lens, far beyond the limited aesthetics of the snapshot. A good example is the 1967 double portrait Britt Ekland and Peter Sellers, 1967. They were at the time film stars each with their own career - both talented, wealthy and successful - equals in every sense and a model couple for the new generation coming of age in the sixties that sought to begin the process of eliminating the class distinctions between men and women, in which the man usually took the role of master of the house and the woman the role of housekeeper. Sellers talks on a, then very rare, car phone while Ekland exits. The two are framed within the frame of the car window, uniting the two. While that might seem obvious since they were then a couple, it is clear that the two are occupying very different psychological spaces despite their proximity. Does this hint at the separation soon to follow? Sellers sits calmly and looks to his left, deep in the middle of a conversation, while Ekland, in the midst of casually moving off, looks up at something outside the frame, dramatically opening up the image to what lies beyond. This use of the open frame is, again, a typical formal strategy of the period. The contrasts of movement and stasis, of communication and silence, of closeness and separateness, are beautifully articulated in a shot that seems carefully planned and spontaneous.

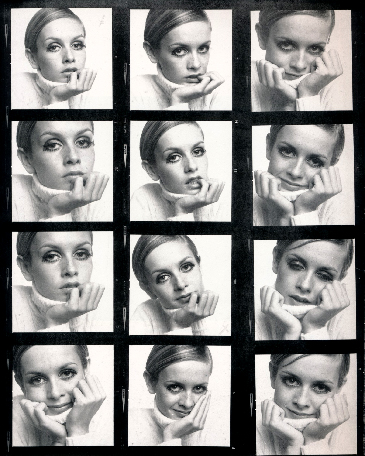

Ronald Traeger, Twiggy Battersea Park, London 1967

While all of the Young Meteors photographed the model Twiggy - to the delight of young and old - she is perhaps the collaborator that is most closely tied to Traeger's successful fashion work. The sense of spontaneous play that was his trademark style was pushed to new heights with Twiggy, perhaps because of her short close-cropped hair and skinny frame she sometimes resembled an adult/child. Traeger used that aspect of her physical beauty and temperament in his shot Twiggy Battersea Park, London 1967. Twiggy, mouth fully open, perhaps screaming in delight, sits astride a mini bike on a dirt road, perfectly caught between childhood and adulthood - the two seem to merge and create a sense of extraordinary play. This giddy delight is both very much of its time, but also transcends it to state a philosophical case for the permanence of childhood, at least as a conceptual space that is more about the experience of childhood as an idea that can be expressed through the body by an adult. It is a phenomenological position, but to understand how philosophy works in a pictorial sense we need to look at Traeger's earlier work in Italy, made when he first set foot in Europe.

Ronald Traeger, Proof Sheet, Twiggy, 1967

Traeger's Roman pictures from 1962 are in effect his portfolio by which he secured the fashion work of the mid sixties. The Roman images consistently juxtapose a graphically imposing foreground, often in silhouette, with a distinct but fragmented background. The long focal length lens flattens foreground and background that then work dramatically together – as in musical counterpoint – by playing interlocking shapes one against the other. Organic shapes mirror man made surfaces; negative spaces come forward and foregrounds recede; the archaic is juxtaposed with the contemporary; Christian iconography is played off against Marxist symbols; people in dramatic movement play off against solid stationary masses; assertive foregrounding of empty spaces plays off densely populated areas. In short the work is about these very urban paradoxes. The work in many ways resembles the films of the French New Wave – Godard’s Breathless (1960), Truffaut’s The 400 Blows (1959), Agnès Varda's Cleo From 5 to 7 (1962) and Éric Rohmer's The Bakery Girl of Monceau (1963) are Traeger’s true contemporaries. The French New Wave traveled across the channel in the late fifties and early sixties and had a profound influence on British filmmakers and photographers. It is the kind of work that resists conceptual summarizing truths in favor of a fragmented collage aesthetic that Traeger gravitated to as the decade progressed, making collages, and even a comic strip using photographs and hand painted balloons with dialog.

A sensibility like Traeger's, fascinated by paradox and contingency, cannot help but see comedy and tragedy, historical locations and everyday life, as an organic whole. In a sense this viewpoint makes every moment precious since it is preordained that it must, like everything else, pass into oblivion or into some cosmological sense of time that we can perhaps never understand. Traeger was an artist fascinated by the complex, organic minutiae of the quotidian at the expense of any theory that might explain reality by fitting it into an organized system of knowledge. This is precisely where he departed, literally and figuratively, from his teachers, still tied to the decorous, sober, conceptual tableaus of advertising and fine art then in vogue.

Ronald Traeger, Rome Series, 1962 The soccer ball and the ball at the top of the Cathedral in play.

Finally, Traeger’s pictures are eloquent about what Proust called the “tyranny of the particular.” This was Proust's term for the sensual stimulation of direct experience that overwhelmed Proust because he made himself be completely open to it – most people don’t for the obvious reason that to do so requires a cork lined room to then be able to retire to - a luxury most people do not have or want. That “tyranny of the particular” that so disturbed Proust haunts Traeger’s images. The long lens has flattened and compressed not only space but also time. A picture of a child playing against the light falling on the side of St. Peter’s Cathedral has the soccer ball and the architecture playing against each other and making connections, and we understand that it’s Traeger playing as well - and he is asking us to come and play with him. It is as if the time between childhood and adulthood were not only suspended but that it had become a space that one can see and hold in one's hands. That's the thing that Traeger found with his camera in Italy, and he never forgot it - and that is why his photography suggests phenomenology but manages to transcend it as a concept. He accomplishes this by grounding the work in the reality of his own time, allowing the non sequitur and the exception space to breathe. It should go without saying that fine art photography, as well as advertising - the two sides of the same coin - are conceptually based so reality is merely there, if at all, simply as window dressing, or worse, as a backdrop to a piece of theater. Traeger understood in his work how the present tense of photography also contains traces of the past and the future, but that this cannot be interpolated - rather, it must be discovered in the world at large. To paraphrase an old saying 'one need not believe in miracles to experience them, but one must be present.' Traeger only had a few years as a working photographer but he was present, and with his camera he allows us a glimpse into that miracle. In that sense the images can’t help but be an invitation to a life of engagement, of exchange, of the senses. The tyranny of the particular, or more to the point the delight of the particular, has not been better served since.

©George Porcari 2016

1. Roland Barthes, The Photographic Message, in The Responsibility of Forms, (Hill and Wang), 1985

2. Martin Harrison, Tessa Traeger, Ronald Traeger: New Angles, (Schirmer/Mosel), 1999

3. Martin Harrison, Young Meteors: British Photojournalism: 1957-1965, (Jonathan Cape), 1998

4. Martin Harrison, Young Meteors: British Photojournalism: 1957-1965