The Arc of a Dive: Photographs by Alexander Rodchenko and Leni Riefensthal

Published in CineAction magazine 2015

We think of photographs as works of art, as evidence of a particular truth, as likenesses, as news items. Every photograph is in fact a means of testing, confirming and constructing a total view of reality.

John Berger – The Sense of Sight

The daily papers talk of everything except the daily. The daily papers annoy me, they teach me nothing. What they recount doesn’t concern me, doesn’t ask me questions and doesn’t answer the question I ask or would like to ask. What’s really going on, what we’re experiencing, the rest, all the rest, where is it?

Georges Perec – Approaches to What?

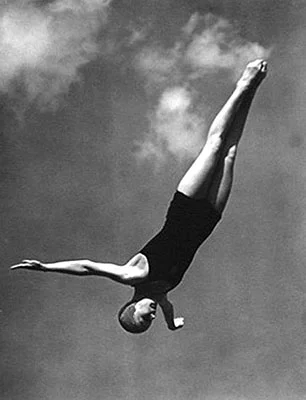

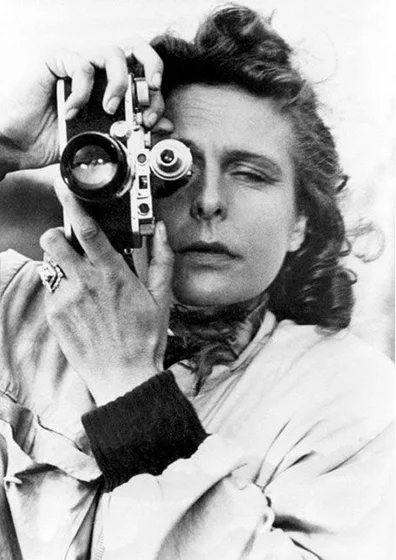

Leni Riefenstahl 1936

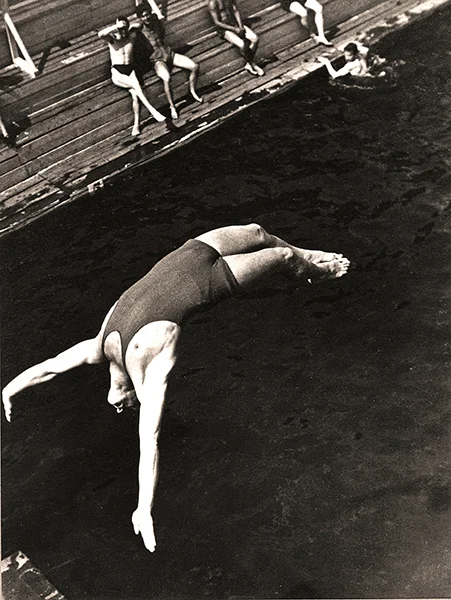

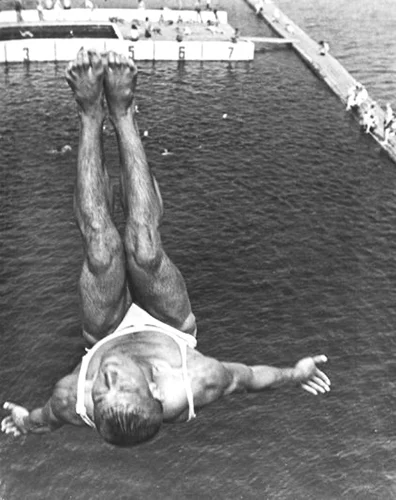

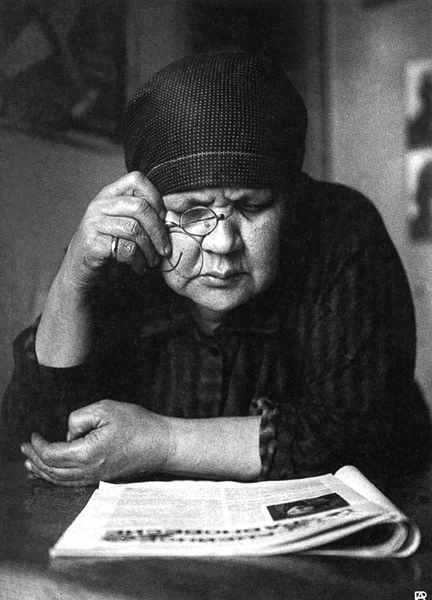

Alexander Rodchenko 1934

It is not unusual that Alexander Rodchenko and Leni Riefenstahl would both find themselves photographing diving competitions and sporting events throughout the years 1933-1936. They were both celebrated artists in their fields working at the peak of their powers. He was a collage artist, graphic designer, photographer and painter, and she was a filmmaker, photographer, dancer, and actress. What they had in common was that photography was something both had mastered despite the fact that neither Rodchenko nor Riefenstahl at the time considered themselves exclusively photographers, and neither of them thought of themselves, in any sense, as journalists. They used photography, and the language of photojournalism, to make art and to fulfill their obligations to their respective high profile clients as they were both working for the propaganda-news sectors of their respective countries, Russia and Germany.

The Olympic games of 1936 held in Berlin, and the trials leading up to it, would allow them a chance to show what they could do in photography and film and to express ideas that both artists had been developing in their work. However, there was more at stake, in part because the photography of athletic events held special meanings for all concerned peculiar to their time and place, and in part because both artists were at turning points in their careers.

According to Alexander Lavrentiev: “Sport was not merely a symbol of strength, agility and the quest for new records. In Russia sport symbolized social liberation, given that prior to the Revolution only the better situated members of society took to gymnastics, figure skating or light athletics.”[i] The photography of sports for Rodchenko and the more radical artists of the post-revolutionary years was part of a general trend toward a democratization of cultural activities depicting working people enjoying classical music, reading newspapers while having a coffee, talking on their own phones, going to a museum, or swimming and diving in Olympic pools. These were all activities that had before 1917 been the province of the wealthy and the privileged. These pictures, which to westerners might look banal, slice of life, and quotidian, held a special meaning to Soviet viewers that signified economic progress, cultural emancipation and hard-fought-for freedoms that could not be taken lightly.

For the Third Reich the Olympics were to be a test of their abilities in public relations. The competition was seen by many journalists of the time as analogous to the growing militarization that was then prevalent, but the Nazis took a more sophisticated approach to the Games than journalists imagined.[ii] This is David Welch: “The Olympic Games were held in Berlin only a few months after the uncontested remilitarization of the Rhineland… and were to be an exercise in national respectability. Albert Speer noted that ‘Hitler exulted over the harmonious atmosphere that prevailed during the Olympic games. International animosity toward the National Socialist Germany was plainly a thing of the past, he thought’… Even before the Games had begun, specific instructions had been given to the various media on how the event was to be covered… signs such as “Jews not admitted” were carefully taken down from the restaurants, hotels and shops… the Games were to prove an ideal vehicle for Joseph Goebbels's propaganda and his strategy was not without success.”[iii]

Olympia 1936 Leni Riefenstahl

Alexander Rodchenko 1934

Interestingly the Nazis had a similar master plan to the one outlined by Stalin’s Soviet sports/leisure programs. What they had in common was a totalizing system that would systematically regulate and control people’s self-image - a propaganda machine that would be formulated within the context of sports and leisure. The Nazis developed something called Strength Through Joy that was, within a short time of Hitler coming to power in 1933, the largest tourist operation in the world.[i] They achieved this through massive influx of cash from the state, as Hitler and the Nazi Party considered “bread and circuses” one of the central pillars of their new thousand-year Reich.

The Nazis felt that they had to wean the working classes away from Socialist and Communist unions and they perceived that the way to do this was through granting workers previously unimaginable leisure time and subsidized vacations that would include indoctrination into Nazi ideology. For example, under the Nazi leadership workers could take cruises to the beaches on the Baltic and summer holidays on the beach. Of course, these activities would be carefully monitored, and would consistently and continuously deliver propaganda about the Nazi Party, making sure that the worker and his family understood that this holiday was not a right prescribed by a union, but a gift from the all seeing and all knowing “father” or Fatherland.[ii] This propaganda “used the new technologies of radio and film to sway millions with its visions for a new Germany – reinforced by fear-mongering images of state “enemies.” The Nazis understood that the language of family, faith and homeland could be used to justify brutal violence against any enemy represented in the media as being opposed to these things. That is why, at least initially, Fascists in Germany and elsewhere depicted themselves merely as the “antidote” to Communism and Socialism. In Nazism’s early stages there were Italian Jewish fascists,[iii] and in the US the “America First” movement in the 1930’s sympathized with aspects of Hitler’s ideology, which borrowed from America’s own Jim Crow laws. These Nazi propaganda images promoted indifference toward the suffering of neighbors, disguised the regime’s genocidal actions, and insidiously incited ordinary people to carry out or tolerate mass violence.”[iv] After 1938 even children’s board games were created where boys and girls would throw dice to move Jews out of a city. These games would not necessarily make children Anti-Semitic but would effectively normalize violence prompted by Anti-Semitism.[v]

In place of Weimar entertainments that in a broad sense promoted the clash of different cultures, art forms, and languages as something invigorating and positive, the Nazis reacted violently against this new open civilization that they considered not only morally depraved but also fundamentally destructive to German identity. Despite very positive elements within Weimar society that involved greater cultural equality, social programs, and sexual liberation, there was also massive endemic poverty, staggering wealth inequality, and a scared, economically unstable middle class. It was a world of urban alienation, displacement, and atomization; old and new bigotries came to the surface as the general population fought for the available jobs and handouts; Weimar was a fast paced society of short-lived media frenzies and political parties that tended to radicalize easily and turn to violence.

The Nazis saw themselves as fighting the good fight and they countered the relative success of the Weimar republic with rallies that included popular German culture. This is Peter Range: “Goebbels propaganda department adopted modern advertising techniques, employing simple slogans, bright colors, and frequent repetition to generate what one historian called “an assault on the collective subconscious.” Sporting events and so-called German evenings – beer and rhetoric – were popular attractions that also generated revenue for the Nazis.”[vi]

Triumph of the Will Leni Riefenstahl 1934

Goebbels sought to undermine class warfare, not by eliminating the upper classes as had happened under Lenin’s Soviet regime, but rather by mixing classes and diluting their respective identities as a class. For example the cabins in the large Nazi cruise ships would not be segregated by class, as was then (and now) the norm, but would be offered by lottery, thereby assuring a mixture of classes and types of people. The two things that would then unify these different groups, who ordinarily would never meet, would be their common German language and culture – all other differences were to be slowly erased over time. The idea was that these new Germans raised under such a system from childhood would think as one, following the lead of their Führer. Not surprisingly the Strength Through Joy program was an enormous success and visitors from abroad with some power in their respective countries sought to emulate the new German system into their own country.[i]

The Olympic games, and Riefenstahl’s film of the event, was from the beginning a calculated media campaign to create a particular impression and to achieve certain goals. The first order of business was to make it clear that under the new Nazi leadership Weimar culture and the influx of a wildly diverse immigrant culture, with a crosscurrent of customs, (many linked to Socialism), had been stemmed, therefore the new regime was “business friendly;” secondly to show that the sexual liberation and open tolerance of the previous regime was at an end therefore the new regime was “family friendly;” thirdly to outshine and outclass the previous Olympics from 1932 held in Los Angeles and thereby showcase the superiority of the German system; and last and perhaps most important of all to ingratiate the Third Reich into the world community as a civilized nation that commanded respect, envy, and fear. These efforts were successful on all fronts. As the New York Times succinctly put it: “Germany is back into the fold of Nations.”[ii] This headline makes it clear that the American ruling elite was, in its own way, also wary of Weimar culture and its openness to radical politics and cultural relativism, tentatively welcoming the new changes in Germany.

This radical politics, made manifest in Russia with the October Marxist Revolution in 1917, openly sought to transform all of society including photography. Rodchenko was experimenting with extreme and unusual angles not seen before, often taken from rooftops or from ground level looking up, fragmenting and abstracting the image while also de-familiarizing the everyday life of Moscow that was the subject of his work. Angles were often askew and he generally used an open frame suggesting that an image is merely a part of a larger, more complex, unseen whole - a mediated fragment. This fragmentation often expressed a playful visual metonymy. In many of Rodchenko’s portraits people are often looking at something we cannot see outside of the picture plane as the open frame became a recurring motif.

By 1936 this is a body of photographic work that Rodchenko had spent almost two decades in nurturing and developing alongside his wife Varvara Stepanova, an artist working alongside him in the same Moscow apartment that they shared. In the new Soviet era there were regular exhibitions of his photography, paintings and collages that would be enormously influential to later artists, particularly in the Bauhaus. These movements included Neue Fotografie (New Photography), and Neue Sachlinchkeit (New Objectivity), schools that would define German photography for the remainder of the century and beyond, despite Nazi propaganda that considered such work a form of “degenerate art.”[iii]

Rodchenko was one of a group of Constructivists who sought to use de-familiarization to give a shock to the viewer’s sense of recognition, forcing them to reconsider the nature of the artwork itself. The observer, under these circumstances, would presumably see reality without the bourgeois preconceptions that presumably straightjacketed spectators into stock responses thereby limiting their ability to think for themselves. For the writer Victor Shklovsky – who articulated the ideas of de-familiarization as a theory - perception was a creative act that people performed for the most part unconsciously, and thus could be easily manipulated by shrewd propaganda and advertising.

Varvara Stepanova Alexander Rodchenko 1932

Both Rodchenko and Shklovsky sought new ways to counteract traditional conventions of image making. One possible way to neutralize this passivity was to startle the viewer into a new way of seeing by some jolt to the system that would slow down looking and allow the individual to perceive in different and more complex ways, perhaps seeing relationships not previously considered. In effect, de-familiarization encouraged the viewer to respond critically rather than to have a knee-jerk emotional reaction. This de-familiarization was analogous to Ezra Pound’s exhortation (before his move to fascist rhetoric) to “make it new,” and to Bertolt Brecht’s ideas for a new theater, but they were perhaps most spectacularly developed in the cinema. It is in the work of Sergei Eisenstein, Dziga Vertov, Hans Richter, Walter Ruttmann, and Jean Vigo that the search for the new found its most powerful visionary artists. In 1917, the year of the Russian revolution, Rodchenko was 26, and like many young people, particularly in the arts, theater and film, wanted a fresh start. Shklovsky’s ideas were germane to this search for the new.

Throughout the 1920’s Riefenstahl clearly delineated an aesthetic of myth-narratives in her financially successful mountain series, consisting of seven films made over eight years (1926-1933). These were melodramas that followed the boy-meets-girl template that had been standardized by the 1920’s. Unlike most melodramas that took place indoors, usually in exotic chateaus or mansions, the mountain films were shot on location outdoors, often using documentary elements that would come to play a part in the narrative. The emphasis on the mountain films was on a theatrical sensibility, sensitive to subtle nuances of emotional cues, but using decorative, traditional framing that depicted grandiose landscapes and the heroes that traverse them - or in their terms conquer them. The blocking and mise-en-scène followed the formulas dictated by the film industry in Hollywood, including a fairy tale aspect that was always present as a subtext. The lighting subscribed to what in the 1920’s and 1930’s was called “the Garbo effect,” that is, glowing, shimmering close-ups done in the studio, with a strong key-light that washed over the face eliminating details giving emphasis to the eyes that were accented with make-up.

Riefenstahl favored a closed frame with all of the formal elements clearly laid out, pointing to a central subject that was then contained within the shot suggesting that the image had captured the essence of the scene. Hers was a totalizing quest for meaning that was rigorously tied to mythic narratives regardless of the content. The other influence on the mountain films were the sporting images of the time that were seen regularly in advertising and fashion magazines that depicted healthy, vigorous young people embodying the Nazi idealization of the Aryan ideal – personified in the mountain series by Riefenstahl herself who starred in all of the films.

This cult of the body was not peculiar to Germany but rather to the West as a whole with each country doing its own variation on the theme. In the US this body cult was led by the entertainment industry, most conspicuously by Douglas Fairbanks, Dorothy Lamour, and the star system in Hollywood. In Germany this body-cult was based around sports and leisure activities, as these far surpassed the popularity of the more lurid entertainments available during the Weimar period. Its one uniquely German component was what they called Freikörperkulture – or “free body culture.” This was a fad for outdoor nudism where “whole families turned up and dressed down for the weekly ‘naked day’ at the outdoor swimming in the vast Luna Park amusement center in Berlin.”[i]

Riefenstahl’s early mountain films were in the beginning co-directed by Arnold Franck, but Riefenstahl was a fast learner and didn’t like to take orders. By the end of her alpine series Riefenstahl was the sole director.[ii] These works were, as Susan Sontag described them, “… pop Wagnerian vehicles… an irresistible metaphor for unlimited aspiration toward the high mystic goal, both beautiful and terrifying, which was later to become concrete in Fuhrer worship.”[iii] When Riefenstahl joined the Reich Minister of Propaganda to shoot the Nuremberg rally in 1934 Goebbels had already been producing films as early as 1929. “… (the) first movie was called Battle in Berlin, a tableau of anti-Semitic imagery paired with filmed street fights between Nazis and Communists. The combat scenes were probably staged or openly instigated for the cameras. Still, the bloody pictures conveyed the Nazis’ commitment and willingness to use violence for their cause. Even if street violence bruised the Nazis’ public image it had the political upside of keeping them in the news. In Goebbels’s Berlin film the roughneck imagery was augmented by documentary footage of long-bearded Eastern Jews on Berlin’s fashionable Kurfürstendamm – pictures that underlined the Nazi message…By the 1930 election, eight films had been produced for distribution to party meetings.”[iv]

We can see from this description that Goebbels was already combining documentary and fiction to create an emotionally resonant effect. Riefenstahl would take this idea much further by fusing the two into a much more cohesive and powerful work of art. These films, and later the propaganda films made by Riefenstahl, were part of what the sociologist Sigfried Kracauer called the “distraction industries” - they were films meant for the salaried masses, the group who would eventually vote Hitler and the Nazis into power.

Diver 1936 Leni Riefenstahl

Diver 1934 Alexander Rodchenko

Kracauer in his study of fascist art and cinema shows how the aesthetics of the mountain films was transferred easily to Triumph of the Will (1936), Riefenstahl’s faux documentary on the Nurenberg Nazi Party Convention of 1934. “The films picture the horrors and beauties of the high mountains, this time with particular emphasis on majestic cloud displays. That in the opening sequence of the Nazi documentary Triumph of the Will similar cloud masses surround Hitler’s airplane on its flight to Nuremberg reveals the ultimate fusion of the mountain cult and the Hitler cult.”[i]

In the mountain series Riefenstahl is a highly sexualized character, particularly in her lingering close-ups, but unlike the overheated melodramas made in California before the Hays Code, no nudity or sexual acts were ever depicted. The films reference sexuality and significantly put it on hold in the traditional manner of Puritan art, which manages to be sanctimoniously asexual while simultaneously suggesting an idealized eroticism transformed into a spiritual force that is powerful and intoxicating. Puritan art always envelops its eroticism in a divine or transcendental light suggesting an otherworldly, mystical, hyper-sexuality. Susan Sontag: “Fascist aesthetics is based on the containment of vital forces; movements are confined, held tight, held in.”[ii] The obvert, carnal and playful sexuality of Louise Brooks in G. W. Pabst’s Pandora’s Box (1928), or Marlene Dietrich in her louche, sexually charged series of films with Josef Von Sternberg, where she toyed with sexual identity and role playing, were considered decadent, obscene, and degenerate by the cultural overseers of the Third Reich.

In Triumph of the Will the sex object is no longer the young vigorous female but the strong male leader with an iron will - a sexualized superman who comes dressed for war, ready to lead his people to their manifest destiny. The massive staging of the Nuremberg rally was put on as a spectacle to be filmed, and when retakes of speeches that had experienced technical problems in the recording were necessary, they were redone in a studio.[iii] It is both absurdly comical and terrifying to think of the leaders of the Reich doing overdubs in a studio to their own images on screen.

Kracauer makes a telling comparison of the sense of theater involved in the production of the Nuremberg rally with the sorts of deceptions common in earlier centuries when royalty ruled Europe: “[Triumph of the Will] represents the complete transformation of reality, [and] its complete absorption into the artificial structure of the Party Convention. The Nazis had painstakingly prepared the ground for such a metamorphosis: Grandiose architectural arrangements were made to encompass the mass movements, and under the personal supervision of Hitler, precise plans of the marches and parades had been drawn up long before the event. Thus the Convention could evolve literally in a space and a time of its own; thanks to perfect manipulation, it became not so much a spontaneous demonstration as a gigantic extravaganza with nothing left to improvisation. This staged show, which channeled the psychic energies of hundreds of thousands of people differed from the average monster spectacle only in that it pretended to be an expression of the people’s real existence. When in 1787 Catherine II traveled southward to inspect her new provinces, General Potemkin, the Governor of the Ukraine, filled the lonely Russian steppes with pasteboard models of villages to give the impression of flourishing life to the fast-driving sovereign; instead of pasteboard, however, they [the Nazis] used life itself to construct their imaginary villages.”[iv]

Riefenstahl in effect used reality as a stage and the people as actors in a contemporary costume drama. Riefenstahl’s photographic and film work for the Third Reich are documentaries by default, but their design was far more subtle, complex and insidious. The elements of reality were in fact real, but they were orchestrated as an ensemble to play a part in an elaborate, dramatic, fictional construction. Yet it would be wrong to say that everything in the films is a prop and everyone an actor, as the films have a high degree of narrative complexity that make such generalizations impossible. Riefenstahl understood that all films are documentaries and fictions at the same time but that they emphasize certain conventions that tell us whether we are watching “fact” or “fiction.” What she did was to erase that boundary and make it her playing field.

But the faux documentary, from where Triumph of the Will finds its lineage, was not her invention, as the form had been pioneered at the very beginning of film history in the late 19th century. These short works were called actuality films, some of which were staged news events. These were shot with actors and sets that depicted contemporary events deemed historically important such as coronations, celebrity marriages, or meetings between politicians. Often these fictional actuality films were shot before the news-event and were released to coincide with the occasion to capitalize on audience interest. Some of these fiction-actuality films mimicked real documentaries by shooting from some distance away, as if the cameraman had not been able to get closer, or the image was partially obstructed by a hat or a tree. This sense of play or mimicry within actuality films is a fascinating example of modernist cinema within a popular genre that was in no sense considered art – on the contrary actuality films were, unfortunately, considered disposable, and once the event they depicted passed many of them were lost or destroyed.

In essence the actuality film continues to be used today in dramatic reenactments of news events using actors, usually accompanied by a voice-over explaining the action, and then using a hand-held camera that mimics the documentary form; and it is also used in reality television that combines scripts and careful blocking with people playing themselves in their real homes. Triumph of the Will used the techniques of actuality films, but was much more sophisticated, as it brilliantly used the language of documentary – treating it as a style – and superimposed on it the full theatrical force of a dramatic, almost operatic, sensibility.

Riefenstahl’s documentaries are dramas that used reality and the visual cues of the documentary form to create a theatrical spectacle with a clear, fictionalized, thematic and narrative thread. In Triumph of the Will a savior comes from the sky (Hitler arrives by plane) and receives the unconditional love and the mandate of a people to lead them to greatness, to victory in war, and, as the title makes explicit, to a “triumph of the will.” This savior is modeled on stock characters seen in the popular writings, from that time, of Karl May and other authors of adventure stories filtered through the writings of Friedrich Nietzsche and the bombastic, epic operas of Richard Wagner.

This conscious blending of fictional narrative and stylistic devices with the documentary was also being explored by other directors during this period, such as Orson Welles in It’s All True (1941), Robert Siodmak in People on Sunday (1930), Roberto Rossellini in Rome, Open City (1945), and Michelangelo Antonioni in The Vanquished (1952). There are, of course, vast differences in how these directors approached this new composite essay/fiction form, yet for all of them it became a way of exploring subjects that resisted easy explanations, categorizations, or summations. This polyphonic fiction/documentary hybrid enabled the use of multiple perspectives within the same work, with none having dominance or giving the viewer the easy but false alibi of an objective or dispassionate viewpoint. We can see that the subsequent work of Welles and Antonioni in particular, with films such as F is for Fake (1974) and Blow-Up (1966) respectively, builds upon the foundation that they constructed in this earlier work.

Riefenstahl did not pursue this line of inquiry. In her work, the powerful dialectical relationship between the two contrasting forms of documentary and fiction is manipulated to the point that reality and theater become one - a conceptual all-embracing “aestheticizing of politics” (Walter Benjamin) - that is formally very complex, but whose overall poetics is simplistic as the single overriding concept guides the work toward only one possible meaning or conclusion. In the case of Triumph of the Will the warrior/savior brings purpose and direction to the people and unifies all differences into a single overriding emotion of euphoric solidarity and wellbeing.

Unlike Roberto Rossellini or the other directors searching for new narrative forms, for Riefenstahl there was never a question of exploring the various levels of reality, the relationship of individuals to their environment, or the psychologies of crowds and power. Instead she championed an ideology through the established conventions of the heroic genre seen in her mountain films. This body of work was the foundation for all of her subsequent films and photography. Yet unlike the other hired artists in the Nazi talent pool who were hopelessly antiquarian, moralizing and sententious, in Riefenstahl the Nazis found an aesthetic visionary who could understand the complexity of the ideas and emotions involved and how they related to the present moment. Just as importantly she could communicate this to masses of people so they would be emotionally moved leaving the rhetoric, which she found pedantic and boring, to politicians and intellectuals. A close look at her photographic work during the Olympics allows us a glimpse into her techniques and their underlying philosophical ideas.

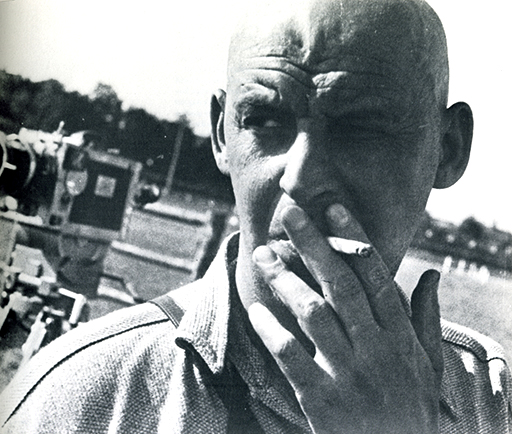

Self Portrait 1935 Alexander Rodchenko The radical open frame seen to full effect, with a slanted horizon that tilts right as the subjects looks off camera left.

Self Portrait 1939 Leni Riefenstahl The classical style adapted to photography and the closed frame seen to full effect, with the camera's two "eyes" perpendicular to the frame as Riefenstahl's hands create a closed circle.

Riefenstahl was working for the Reich under Joseph Goebbels, the Reich Minister of Propaganda, and was to photograph and film all of the Olympic events overseeing the details of hiring crews and supervising them. For her previous film Triumph of the Will she had at her disposal thirty film cameras and a staff of a hundred and twenty members, not including the architects and designers who created the “set” for the Nuremberg rally that was the climax of the film.[i] For the Games Riefenstahl had sixty cinematographers at her disposal and the film was, as to be expected, elaborate and ambitious. Her editor Walter Ruttmann and his many assistants had to assemble thousands of hours of footage into a coherent narrative that followed the trajectory of the games themselves. The film was eventually shown on its release in 1938 in two parts: Festival of the Nations and Festival of Beauty, each emphasizing a particular aspect of the games.

Ruttmann was himself a highly talented filmmaker who had made a series of short avant-garde films such as the abstract Opus 1 (1922) and the influential Berlin, Symphony of a Great City (1927). But during the Nazi period Ruttmann shifted his allegiance from his avant-garde work, which the Nazis regarded as decadent and elitist, to making propaganda films for the Reich. Later during the war he was killed in 1941 while filming the German advance on the Russian front, in the summer months, before the winter retreat.

Realizing that the light during the actual diving competition was midday light, direct and flat with deep shadows, Riefenstahl asked the divers to perform their dives outside of the competition in the early morning so she could shoot them in the light of dawn.[ii] In this way, she avoided presenting the divers in the harsh daylight that would remorselessly show every straining muscle, every bead of sweat and every hair. The face of divers in mid-dive is often not flattering because of the immense strain and concentration involved and the silhouette avoided this problem. The divers became anonymous types so no particular qualities could be ascribed to any of them except gender.

Some of the divers agreed to the off-hour dives and the images of bodies taking off in the morning mist are photographed by shooting with a strong back light from the rising sun. The resulting silhouettes turn the divers into anonymous types that appear to be flying and to have none of the strain of divers as they make their difficult acrobatic moves on the way down to the water. For a fraction of a second humanity appears to have conquered mundane gravity, and the divers float playfully in space.

In Olympia the marble of classical Greece is finally made into a living being that is both in movement and frozen, the two opposites in perfect harmonious balance. While some of the divers are naked in Riefenstahl's work their nudity is there not so much to titillate as to make the connection to classical art absolutely clear. The aesthetics in Olympia are up front and center in a way that was not evident in Triumph of the Will because in that film they were subordinated to consistently mimicking the documentary style. We can summarize by saying that in the latter film the politics is overt and takes center stage, in every sense, while in Olympia, a far more sophisticated film, the politics is a subtext that is subtle but constant, and it is seamlessly integrated into the aesthetics of the film. In effect the sports in Olympia is the bait, while the substance of the film lies in its formal effects and its metaphors.

Rodchenko in the 1930’s was working for Building the USSR, a newspaper that disseminated news and propaganda, and was shooting various preliminary competitions as preparation for the Olympics. Rodchenko shot his divers from above so that the crowd below watching and the diver would be in the frame at the same time. What was his reasoning? The architecture of the arena and the crowd, dressed in ways peculiar to their time, would automatically historicize the image and ground it (literally and figuratively) in the present moment. Rodchenko was after a certain dialectical tension between the dive and the historical circumstances surrounding it. His choice of 35mm film, then a relatively new format (first made available in 1925) and his assimilation of the snapshot aesthetic, were consciously anti-classicist. Rodchenko was keenly aware of the divide in photographic ideology during the 1930’s. A brief look at the warring aesthetics in this time throws light on the differences between Rodchenko’s and Riefenstahl’s work.

Olympia 1936 Leni Riefenstahl's "petrified eroticism."

Watering the Streets 1932 Alexander Rodchenko

On the one hand photographic classicism, otherwise known as Pictorialism aspired not to take pictures but to make a works of art, and its mantra, repeated in various journals in support of the style, particularly Camera Work that was edited by Alfred Stieglitz, was “The business of a work of art is to make an effect, not to report a fact.”[i] It came of age officially in 1910 when Stieglitz’s 291 Gallery in New York had an exhibition and some prints were purchased by museums including the Albright-Knox Gallery.[ii] Riefenstahl clearly belonged to this camp.

On the other end of the photographic/ideological spectrum was the documentary or “anti-graphic” aesthetic (as it was called at the time) exemplified by Walker Evans and Dorothea Lange. This group received formal recognition in 1935 when the influential New York dealer Julien Levy, then famous for championing avant-garde and surrealist art, put on an exhibition entitled: Documentary and Anti-graphic Photographs by Cartier-Bresson, Walker Evans & Alvarez Bravo.[iii] Rodchenko consistently sided with the documentary artists, pushing his snapshot aesthetic and his highly developed sense of radical formalism to extremes, until the boundaries between personal, intimate snapshots, photojournalism, and art photography were erased.

Aarguably the most spectacular blending and disruption of photographic categories occurred at the Bauhaus, (1919-1933) in Germany, and later at the radical New York’s Photo League (1936-1951) in the USA. Not coincidentally the Bauhaus was permanently shut down by the Nazis when they came to power in 1933, and the New York Photo League was forced to disband during the post-war era in the USA that came to be known as McCarthyism. While the Bauhaus re-established itself to some degree in Chicago as the short-lived New Bauhaus in 1937, the Photo League in New York never recovered from the attacks on its members by Senator Joseph McCarthy’s witch hunts that only ended in 1954.

These radical photographic experiments came to an end for Rodchenko and for the artists of his generation, at least in public exhibitions, with Stalin’s crackdown on all avant-garde art in the Soviet Union starting in the 1920’s and gaining traction with his push for an art of “socialist realism” in the 1930’s as a counter to “decadent” Western art. Stalin’s emphasis on a civic minded, heroic, neoclassical aesthetic, ironically, mirrored both Riefenstahl’s film work and the fantasy aesthetic of the movies made by the “dream factory” in Los Angeles. From a certain point of view Olympia has much in common with the film musicals of Stalin era Russia such as Jolly Fellows, and Busby Berkeley’s Dames, both from 1934, in that they sought to deliver a positive message of health, vigor, joy, and success.

To photograph divers using his small Leica Rodchenko would hang from scaffolding overlooking the dive. He had no problems with midday light as it permeated every hair and straining muscle. Rodchenko wanted the porous wetness of skin and the contingent immediacy of the jump in his pictures. Even the awkwardness of some of the divers, and the humor resulting from it, were all emphasized and made into thematic elements in the pictures. The fleetingness and evanescent quality of the moment permeates the image like the water that seems to be everywhere, including the hairy legs of the divers, and the camera is the perfect tool to allow us to see it in the light of day.

The distance between photographer, diver, and audience, and the ephemeral chance elements within the dive all come into play as something contingent and in flux. Because of the unusual angle – the element of de-familiarization – we also become aware of where the photographer might have been standing when the picture was taken. In effect one is asked to consider the photographer's point-of-view. The apparatus itself comes forward and takes up as much thematic space as the dive itself. The audience below mirrors the photographer above and the diver is caught in the middle like a specimen being examined. The self-reflexive act of looking and being seen become primary thematic elements within the work.

Riefenstahl on the other hand was militant about escaping the historical, the factual, the realistic, and she saw her salvation in the presumably timeless universe of classicism where there were no awkward moments, no sweat, and no body hair. This is a fantasy world that presumably existed in the distant past of classical Greece, although the Greeks themselves – as is clear from their writing – had very different ideas about such matters. In Riefenstahl’s work criticism, evidence, and analysis were not merely subsumed but rejected altogether in favor of symbols, slogans and sensation that evoked a mythic past and a passionate “return to order.”

Riefenstahl herself stated it clearly: “Whatever is purely realistic, slice of life, which is quotidian doesn’t interest me… I am fascinated by what is beautiful, strong, healthy, what is living. I seek harmony.”[iv] In this very revealing statement, she assumes that the realistic/slice of life and the beautiful/healthy are mutually exclusive. More importantly, throughout her writings and her work she takes for granted that the harmony she seeks to capture on film is extraneous to the observer and so it must be created by an artist from base raw materials. Riefenstahl had a concept in mind, that she referred to as “harmony and beauty,” and photography or film were the means to that end, rendering not individuals but carefully composed and lit types that represented ideals of beauty and strength.

The modernist idea – post-Einstein and quantum physics – that one affects the search and brings to it as much as one takes, and that this applied to presumably documentary images that recorded reality, was completely foreign to Riefenstahl. When Andre Kertesz photographed a sleeping student in a café or when Dorothea Lange photographed poor laborers hitchhiking to California, they were also interested in harmony and beauty, but it was different from Riefenstahl’s. As she herself said, realism held no interest for her except as coarse, unprocessed material that she could mold into an elaborate fantasy theater – which was also being formulated at the same time by the propaganda machine of the Third Reich – a spectacle that Sontag described as “petrified eroticism.”[v]

Unlike Riefenstahl, Rodchenko was interested and invested in reality. He wanted to not only transcribe it faithfully, as any good photojournalist, but to interact and improvise with it in an almost musical sense like an artist, but he didn’t treat it like raw material waiting for the “master artist” to turn straw into gold. If reality were mud, Rodchenko would like to be knee deep in it, like a kid discovering the pleasures of playing with the earth. In their respective photographs of diving competitions he sees himself as already inside of reality and existentially a part of the action, while Riefenstahl is outside looking from a distance at the bigger concept.

From Riefenstahl’s perspective Rodchenko only got the small picture, what she called “the purely realistic,” but missed the big picture because he had no vision. What is the big picture? What is the vision? The vision is the transcendental moment reaching to a higher spiritual consciousness and to presumably eternal truths such as “purity,” “essence,” and “beauty” that were, for her, fundamental truths beyond the reach of History. For Rodchenko, Riefenstahl missed the crucial moment, as her work was merely Pictorialism in contemporary garb, essentially fantasy illustration more related to the turgid, erotic kitsch of Lawrence Alma-Tadema or J.C. Leyendecker than to any contemporary artist or journalist.

From this perspective we might say Riefenstahl constructed her own reality - a superior one to, as she called it, “the quotidian that doesn’t interest me” - one related to the quality ascribed to the spiritual. Susan Sontag: “A principal accusation against the Jews within Nazi Germany was that they were urban, intellectual, bearers of a destructive, corrupting “critical spirit.” The book bonfire of May 1933 was launched with Goebbels’s cry: “The age of extreme Jewish intellectualism has now ended, and the success of the German revolution has again given the right of way to the German spirit.”[vi] Clearly Goebbels is not only making a distinction between the intellect and the spirit but suggesting that they cannot coexist – you have to choose. What makes Riefenstahl’s work so seductive for so many people is that the ideas in the film do not seem imposed but grow organically out of the narrative building up like counterpoint in music. This sense of an orchestration of visual contrasts, creating metaphors in the editing, was Riefenstahl’s strong suit. She was a master filmmaker who had few equals, one of them ironically being Sergei Eisenstein, the Marxist Soviet filmmaker and theoretician.

Rodchenko's Mother Reading the Paper Alexander Rodchenko 1932

Fascist art was not strictly about idolizing one man, although that was an important element. It was, as Goebbels’ speech makes clear, about freeing oneself from the burdens of thinking, that is, of doubt. In the embrace of Nazi ideology a person may enter into a realm of ecstatic feeling or spirit. – a state where one could presumably be transformed, as Goebbels stated in a very revealing sentence, “from a little worm into part of a large dragon.”[i] In her work Riefenstahl wanted to synthesize the mannered German kitsch of her mountain films with established documentary techniques fusing them into a documentary-fiction hybrid. In her photographs and films the crowd, the human factor, may play a crucial role but it is always placed there to serve the master narrative and the overriding concept. The crowd in Riefenstahl’s work is there to worship and act as witnesses in the realization of a Hellenic or mythic ideal in modern dress. Her humorless, but emotionally resonant work, was fundamentally an epic, religious fantasy art. She was interested in the mythic and the spiritual as a physical force that emotionally captures and overwhelms the viewer and renders historical or critical reasoning superfluous.

The fact that the end result was fiction did not make any difference, in fact it might even be seen as a positive element. This is Hanna Arendt: “The effectiveness of propaganda demonstrates one of the chief characteristics of the modern masses – they don’t believe in anything visible, not in the reality of their own experiences; they do not trust their eyes and ears but only their imaginations. What convinces masses are not facts, not even invented facts, but only the consistency of the illusion.”[ii] As Arendt makes clear the illogic of the propaganda in no way detracts from its effect or its power. Strong narrative skill transcends all mundane facts and renders them mute – we are effectively mesmerized and in thrall to our own fictions.

For Rodchenko aesthetics always played a subordinate role to his subject and their historical context. It was never about getting the big picture but the small details. He was genuinely interested in people and their present situation and saw photography as a means to seizing the intangible everyday. He saw the historical in the present tense and had an ethnographic and a poetic sensibility that he held in extraordinary dialectical tension when producing his best work. For him it was all about the complexity of the real, and its relationship to his carefully considered point of view that continues to be the lasting source of his work’s emotional power.

The clashing and contradictory aesthetic paradigms of Riefenstahl and Rodchenko are not simply historical remnants tied to the prelude to WWII but are very much with us today as we can see the basic criteria of Pictorialism and “Anti-Graphic Photography” at work in the production of contemporary photographic fine artists, commercial photographers, photojournalists, and filmmakers. Those resonant poetics that come to us from the 1930’s have much to tell us about contemporary life, and the ways that photographers and filmmakers then and now depict them; the way that politics and philosophy interact and interpenetrate with aesthetics; the choices artists make, actively or passively, and their long-term consequences.

©2015 George Porcari

[1] Alexander Lavrentiev, Alexander Rodchenko, Photography 1924-1954, Konemann, 1996

[1] Robert Edwin Hersztein, The War That Hitler Won: Goebbels and the Nazi Media Campaign, Paragon House, 1986

[1] David Welch, Propaganda and the German Cinema 1933-1945, Tauris, 2001

[1] Robert Edwin Hersztein, The War That Hitler Won: Goebbels and the Nazi Media Campaign

[1] Robert Edwin Hersztein, The War That Hitler Won: Goebbels and the Nazi Media Campaign

[1] Jason Stanley, America is Now in Fascism’s Legal Phase, The Guardian, 22, December, 2021

[1] Susan Bachrach, State of Deception: The Power of Nazi Propaganda, US Holocaust Museum, 2009

[1] Susan Bachrach, State of Deception: The Power of Nazi Propaganda

[1] Peter Ross Range, The Unfathomable Ascent: How Hitler Came To Power, Little Brown, 2020

[1] Max Wallace, The American Axis: Henry Ford, Charles Lindbergh and the Rise of the Third Reich, St. Martin’s Press, 2003

[1] Robert Edwin Hersztein, The War That Hitler Won: Goebbels and the Nazi Media Campaign

[1] Stephanie Barron, Degenerate Art: The Fate of the Avant-Garde in Nazi Germany, Abrams, 1991

[1] Peter Ross Range, The Unfathomable Ascent: How Hitler Came To Power

[1] Stephen Bach, Leni: The Life and Work of Leni Riefenstahl, Vintage, 2008

[1] Susan Sontag, “Fascinating Fascism” in Under the Sign of Saturn (Anchor Books, 1980)

[1] Peter Ross Range, The Unfathomable Ascent: How Hitler Came To Power

[1] Sigfried Kracauer, From Caligari to Hitler: a Psychological Portrait of the German Film (Princeton, 1974)

[1] Susan Sontag, “Fascinating Fascism” in Under the Sign of Saturn

[1] David Welch, Propaganda and the German Cinema 1933-1945,

[1] Sigfried Kracauer, From Caligari to Hitler

[1] Leni Riefenstahl, Olympia, St. Martin’s Press, 1994

[1] Leni Riefenstahl, Olympia

[1] Patricia Albers, Shadows, Fire, Snow: The Life of Tina Modotti, Potter, 1999

[1] Pam Roberts, Alfred Stieglitz: Camera Work, Taschen, 2013

[1] Jeff Rosenheim, Manuel Alvarez Bravo, Henri Cartier-Bresson and Walker Evans: Documentary and Anti-Graphic Photographs: a Reconstruction of the 1935 Exhibition at the Julien Levy Gallery in New York, Steidl, 2004

[1] Leni Riefenstahl interview in Cashiers du Cinema in “Fascinating Fascism” from Under the Sign of Saturn, Anchor Books, 1980

[1] Susan Sontag, “Fascinating Fascism” in Under the Sign of Saturn

[1] Susan Sontag, “Fascinating Fascism” in Under the Sign of Saturn

[1] David Welch, Propaganda and the German Cinema 1933-1945

[1] Hanna Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism