No One Here Gets Out Alive: Federico Fellini's

Toby Dammit

Published in CineAction 2007

“In order to understand, I destroyed myself.”

Toby Dammit The strangely depopulated airport is both hyper-real and fake, ominous and banal. We might assume it is a painting but for the fact that the camera tracks forward into the space, eventually tilting upwards towards the black and white video screen - an image that seems to come from some other time-frame or reality. The sort of space that would later be referred to as a "non-place" by sociologists like Marc Augé.

INSTANT SIMULTANEITY

Federico Fellini's Toby Dammit is a forty minute film made in 1968 at Cinecitta and various locations throughout Rome. It is one Fellini's greatest films - a masterpiece of the late sixties art film that raised several questions, starting with questioning Fellini's own aesthetic reality as the work was made in the midst of a crisis outlined to some extent in his film A Director's Notebook - a kind of first draft to Roma. This auto-criticism was something that other directors were also doing because of a moral crises within the society as a whole that seemed to necessitate a new aesthetic approach. Toby Dammit is part of a whole group of films made around the same time by mostly European filmmakers - but not limited to them - that addressed the collapsing social norms or the "social contract," that seemed to be undergoing radical transformation in the post-war era - and by the 1960's was beginning to unravel. In that respect Fellini's film is comparable to other films from the same period such as Michelangelo Antonioni's Zabriskie Point, Jean-Luc Godard's Weekend, Richard Lester's The Bed Sitting Room, Marco Ferreri's Dillinger is Dead, Andy Warhol's Chelsea Girls, Don Levy’s Herostratus, Liliana Cavani’s The Cannibals, Glauber Rocha's Entranced Earth, Pier Paolo Pasolini's Pigsty, Ken Russell's The Devils, Haskell Wexler's Medium Cool, Jane Arden’s The Other Side of the Underneath, Elio Petri’s The 10th Victim, Nicolas Roeg and Roger Cammell's Performance and Rainer Werner Fassbinder's Love is Colder Than Death (among many others).

What filmmakers intuited in their work was that Marshall McLuhan's "instant simultaneity" created a paradox: that while this instant communication might provide an unheard of horizon of progressive and emancipatory experiences it also created a tribal sense of dread, both existential and generalized. The reason being that - as McLuhan makes clear - in a world of instant communication one can, at any moment receive a message that means "panic start running now!" New means of transport and communication would create a permanent sense of dislocation and displacement as much as they would facilitate movement. The problems - clearly identified in the postwar period by writers as different as Albert Camus, Hannah Arendt, and Herbert Marcuse were a rapidly diminishing human agency and political freedom, and the paradox that as human powers increase through technological mastery and humanistic inquiry, we are less equipped to control the consequences of our actions.

Toby Dammit The modernist video globe - in the form of an eye - contains what looks like an old black and white photograph in a conventional frame with a caption we can't read. Orwell's television that looks back at you comes from the past with an apparently friendly face - modern technocracy at its most insidious.

While there was common agreement that this was the situation at hand there was, as to be expected, radically different methods of finding a solution - if in fact there was a solution. What was understood was that the post-war utopian promises of universal access - via the computer, electronic communication and media, along with unlimited mobility, all presumably facilitated a new utopia, but one that by 1968 was in deep crisis. The actual experience of these postwar utopian spaces at ground level were a different matter: The Corbusian projects outside of Paris; the public sculptures and parks of Stalin's Moscow projects, the molded concrete buildings that formed the planned city of Brasilia (in the shape of an airplane!), the TWA terminal in New York's Kennedy airport (also designed in the shape of a plane) designed by Eero Saarinen that posited a space of controlled transition; or the ironically named "freeways" of Los Angeles that were meant to provide unlimited access day or night from any point to any other point - all of these urban projects created an anomic sense of dread, confusion and panic that was difficult to articulate but pervasive.

These unresolved paradoxes within the West created instability - and a sense of opportunity for the movement of capital for the elites since the new electronic system of "instant simultaneity" would create a much more powerful and interconnected predatory capitalism. Under such a system greater wealth could be accumulated through electronic exchanges, which were fast, than through industrial production, which was slow. In essence speed became the sword in the stone, the sine qua non to acquire, maintain and develop, enormous wealth. Of course this high speed network would simultaneously create a permanent underclass and a profound sense of moral disgust. Toby Dammit, and the other films under discussion, all dealt with contemporary society from what we might call an outraged critical perspective that sought to explore its tragic contradictions from inside the society that created them, and thereby establish a new aesthetic paradigm through critical analysis of that immediate reality, rather than through an abstract or conceptual reconfiguration of artistic practice.

SPIRITS OF THE DEAD

Toby Dammit was one of three short films in an omnibus feature film adapted from stories by Edgar Allan Poe that were distributed together in Italy as Tre Passi Nel Delirio, in France as Histories Extraordinaires, and in England and the U.S. as Spirits of the Dead. The other two short films are William Wilson and Metzengerstein, adapted conventionally within the traditions of the period, by Louis Malle and Roger Vadim respectively. Fellini's film is an adaptation set in contemporary Rome of Poe's Never Bet the Devil Your Head published in 1841. Poe's work was a brief comic satire of the transcendentalist movements that were then popular in Europe and America. Fellini's work takes two elements from Poe's story: First the plot of a drunk who confronts a mysterious stranger on a bridge and bets him his head; the man fails to see that the stranger is the devil who subsequently wins the bet. Second Fellini takes the name Toby Dammit, Toby being an English slang term for ass in Poe's time.1In short Toby Dammit is a dammed ass.

The film begins with a sudden shift from day to night - we see a hand held shot of a romantic late afternoon sky that then abruptly cuts to a static night shot of the interior of a jet’s cockpit. On the soundtrack the sound of a jet is too prominent for an interior shot. Inside the plane's cockpit we see the landing lights of an airport at night directly behind the windshield as we are clearly on a set - a flight simulator re-enacting a landing. We sense the forced simulation of motion that this device, and others to follow, are meant to convey rather than any sense of actual mobility. It is quite clear that nothing is moving and that no one is going anywhere. We hear the voice of Toby Dammit, a British actor played by Terence Stamp before we see him – his voice is decadent, laconic, resigned, bemused, exhausted:

"The plane grew closer and closer to Rome. I knew she would be there waiting for me with her white ball."

Toby Dammit Taking the escalator up but facing backwards - surrounded by people but suddenly alone.

There is a sudden cut to a series of shots, some documentary and some created in the studio, that show the interior of an airport. The shots are highly realistic in depicting a deep space that Fellini consistently uses - in effect accentuating the one point perspective of the camera - but yet they look unreal - like set design sketches. These are the spaces that would later fascinate sociologists and anthropologists, particularly in France, where Marc Augé coined the term "non-place" to describe airports, parking lots and office spaces among others that are so ubiquitous as to be invisible. Each shot inside the airport uses slightly different color filters - mostly in the orange and yellow range - and different camera movements that in the editing do not match – and it is clear that this is done intentionally – but to what end?

Some of these scenes are clearly shot in the airport itself and some are in the studio, but not only is no attempt made to integrate them - as would be a matter of course for a conventional film - but Fellini italicizes the differences. We seem to have only fragments of scenes – nothing is complete. There are abrupt shifts in visual syntax using a variety of cinematic techniques that refuse to cohere, that in fact contradict each other, as if incompleteness and contradiction itself were the key factors in organizing the film's narration. For example a brief shot of a black woman who acknowledges the camera as it moves past her seems to be filmed using a conventional documentary form. That is, she is forced to step back to let the camera past her, the background action appears to be a real airport, and it is shot at eye level. But rather than the familiar hand held motions that would typically accompany such a shot Fellini uses a smooth dolly on tracks, which glides through the space, throwing into doubt the sense that it is a documentary shot. Throughout the film one cinematic convention cancels the effects of another by making the illusion it seeks to create null and void. In Toby Dammit the encyclopedic technical devices, the rapid shifts in cinematic convention and the self consciously awkward camerawork and editing suggest that there are a multiplicity of realities in unresolved conflict. The density of information each short scene contains makes it difficult to see where the scene will go from second to second. There seems to be a resistance on the part of this opening sequence to narration itself. Fellini seems to have sought every possible stylistic convention available to him, yet meaning always seems consciously mediated by a cinematic technique that is inappropriate to the content. His deployment of oblique framing, complex intersecting planes and ambiguous reflections reinforce and make very clear that we are seeing a highly conscious visual strategy. Every time a scene is on the verge of clarification, or a resolving moment seems about to occur it is frustrated by a cut to something that contradicts it.

Toby Dammit The airport.

Toby Dammit The transit lounge turned into a dream space.

Toby Dammit The expression on the face signifies documentary while the background is clearly staged - even the Coca Cola logo behind the woman is contradicted by her incongruous glass of milk. - a world where everything finds its contradiction, its negation on the spot.

A CATHOLIC WESTERN

At Rome’s Leonardo Da Vinci Airport the full color spectrum returns as Toby Dammit stumbles onto a bouquet of flowers, suggesting both a funeral wreath and a traditional welcome. Toby's face is ashen, his matted hair is bleached blonde and he walks forward uncertainly as if afraid to fall. Strobe lights flash from paparazzi as they run for Toby - the proverbial superstar - who escapes to the top a nearby escalator. Strangely the paparazzi do not follow and Toby finds himself suddenly alone as he rides the elevator facing the wrong direction, then steps off into a mezzanine where he mimes the gesture of taking someone by the hand. There is sudden silence as if the photographers and reporters had suddenly vanished as he asks with Shakespearean gravity to no one in particular:

"Why did you come here?"

In conventional Hollywood films such as The Cell or Vanilla Sky the multiplicity of contradictory styles, the italicized jump cuts in image and sound and the manic shifts in tone are meant to be interpreted as mimicking a mind in the process of disintegration, that is, one that is no longer able to distinguish between perception, memory and imagination. The collage effects aesthetically represent the essence of this confusion and allow us to understand its cause if we examine the meaning (usually Freudian) of the images. In more complex works such as Ingmar Bergman’s Persona or Nicolas Roeg's The Man Who Fell to Earth the same is true but the relation of “normal” to “sick” is consciously thrown into doubt because Bergman and Roeg asks questions regarding the nature of identity rather than illustrating “madness.” In conventional films the past determines the present and the future in a systematic way. That is something that is foreign to Fellini; his sense of delight in the chaos of the present moment allows at least for the possibility of something new and unforeseen to occur that is not historically determined. For Fellini collage effects do not mimic the mind only, but rather the friction between the mind and a physical reality that resists summarizing truths. Within a single image we find obvious metaphors (such as a flock of sheep in a cul-de-sac) which direct our attention to symbolic motifs, yet these elements constitute only part of the content of the series of images, as the strongly metaphoric tableaus are inevitably followed by shots that are highly realistic and ambiguous. In effect these more symbolic shots are forced to exist in a context in which they are only one reality among many - a reality that is overfull of visual information, interruptions, delays; a world of complexity and randomness that remains unresolved and without a clearly defined meaning. These fragmented partial views consist of unfinished actions and uncertain conclusions. The narrative that they embody is episodic, not as in Bergman and Roeg, tragic.

In Fellini's work we experience a world of faces, voices gestures, all moving in and out of the frame, all with their own unique characteristics. There seems to be no place in such a world for essences but only for the temporal confusion and the spatial mess of provisional truths. In that airport, recreated in Cinecitta, Fellini contrasts nuns caught in a burst of wind inside the climate controlled space, alongside Muslims wearing the traditional turban. A Hasidic Jew walks backwards into an escalator. Businessmen wear cowboy hats and hold hands surrounded by clear plastic bags full of flowers and trash. The transit lounge becomes a collective dream space. All races and religions meet in transit but never come together - each is in their own self-contained world. The confusion that result from this barrage of disparate sequences are in fact what the film is partially about. From realist filmmakers such as Roberto Rossellini and Victorio DeSica Fellini learned what Martin Scorcesse refers to as a “Franciscan” respect for the world of physical reality - confusions and contradictions intact. Realists as different in temperament as Jean Renoir and John Cassavetes have tremendous respect, first, for the world of the senses, of the body, of expression, of action; and secondly, for the social context that a particular individual is in. But Fellini is not a realist – rather he delays our essentialist reading of his work by using realism and he does the same to a realist reading by using luscious symbolic references and theatrically comic digressions often within the same sequence. In short what we have here is a cinema of paradox

Toby Dammit The limousine taking Toby from the airport to the hotel presents a parade of images including some violent graffiti with a gun and a heart that we see on the glass reflection.

In an alcoholic stupor Toby Dammit rides in a limousine at dusk taking him from the airport to Rome yet the glimpses of the city that passes before him - and that we see through his point-of-view - through the car windows are from various times of the day that do not match the interior shots. The most astonishing of these sequences is of a Catholic procession in mid-day in which an effigy of the crucifixion passes before a concrete and glass modernist building – the warm gold and red of the theatrically baroque statue contrasting with the sleek grid of the modernist tower– the two kinds of power – secular and religious - meet and the statue of Christ seems to dance in front of the building turning it into a backdrop to the Passion. Significantly Toby barely notices the effigy which seems to offer him (an English Protestant) both a greeting and a warning. The car comes to a stop during a traffic jam and a gypsy woman comes to read his palm. On seeing the lines in his palm she closes his hand refusing to read his fate – Toby turns his closed hand into a fist and laughs maniacally as if the closed hand held a precious secret. In the limousine he sits between a priest, who is the producer of the film Toby will make and a woman who is his translator who explains the film he is to make in a humorously fake upbeat monotone voice:

Toby Dammit Toby is instructed by the priest/producer that he is to make a "Catholic Western." Note the cigarette and the openly sybaritic attitude by the priest compared to Toby's ethereal, romantic, ascetic disengagement. Despite their physical proximity the two men occupy radically different psychological spaces.

"This is to be the first Catholic Western. Man is given another chance at redemption as Christ comes back to earth as a cowboy. It will be done with the minimum of sets and shot like Pasolini..."

Toby lurches toward the producer not having heard a word and asks:

"Where's the Ferrari the production office promised me?"

Toby Dammit Toby in the film studio - the busy image is a typical Fellini tableau - the zoom lens on the television camera on the left (a comical phallic prop) is counterbalanced by the crew on set all in their own worlds while Toby's attention is elsewhere off screen.

We understand from this brief scene that Toby is one of many actors from all over the globe, who came to Rome in the 1960's and 70's to work at Cinecitta, the Italian studios then churning out entertainment on a massive scale for an international audience, that produced enormous wealth, at least for the producers and investors, within a relatively short amount of time. Fellini cleverly lays out Toby's role as Christ in this intended "Catholic Western" where Pasolini's Catholic/Marxist aesthetics will be reduced to a style in the manner of advertising. The comically absurd explanation of the priest/producer is cut short by Toby, whose only interest in the proceedings appears to be a Ferrari that the production office has promised him. Such perks within the film industry in Italy were typical of the period.

The central motifs of the classical American Western: violence, men and landscapes, the struggle of man against nature, of good against evil, of civilization against anarchy, all play themselves out in the film we see but most certainly not as it was conceived by the priest/producer. This is an inspired doubling of roles for he is both the intermediary between man and God and man and the financing of the film. His power is tangible - he rides in limousines - yet Fellini goes to great lengths to show us this man as a modern buffoon, as well fed and self obsessed as any CEO or rock star. His enthusiastic gestures as he pontificates about the film, the sweat running down his chubby face, his arrogant earthy laughter, all comically undermine any possibility for transcendence which is presumably the point of his profession, and the theme of the Catholic Western they are to make. As in so much of Fellini’s work the face and the body are far more eloquent than the language the characters use to express themselves. Fellini brilliantly goes beneath the delusions of the speaker by allowing us to see what lies underneath the effects and the facade. For example Zampano’s macho posing as a tough, self-contained and freedom loving gypsy in La Strada is betrayed by a face that is uncertain, hurt and lost. Gelsomina, his partner, enjoys posing as a worldly artiste to small town workers, but unlike Zampano she does not take her posing seriously. Fellini superbly conveys this delicate balance between shifting identities, between interior and exterior, often to create an extraordinary sense of the comic and the tragic simultaneously.

DO YOU BELIEVE IN GOD?

Another abrupt cut takes us to the interior of a television studio where the canned reactions of a simulated audience are controlled by a television director. Toby sits uneasily between a massive black and white photographic collage of himself that serves as a backdrop and the television camera, which hydraulically glides around the room with a comically sovereign power. The pixie announcer crawls along the floor on all fours, by Toby's feet, out of camera range. Arriving at her proper place she begins to contort her face wildly in order to exercise her facial muscles before going on camera. On cue an applause track abruptly starts but too loudly - and she announces Toby to the simulated audience as a great Shakespearean actor. She asks him:

"Do you believe in God?"

"No."

"And in the devil?"

"In the devil yes!"

"Can you tell us what he looks like?"

Toby Dammit - Fellini's shot is beautifully off center dislocating the entire image and creating a sense of dread merely through gesture, lighting and framing. A lesson that was well learned by David Lynch among others.

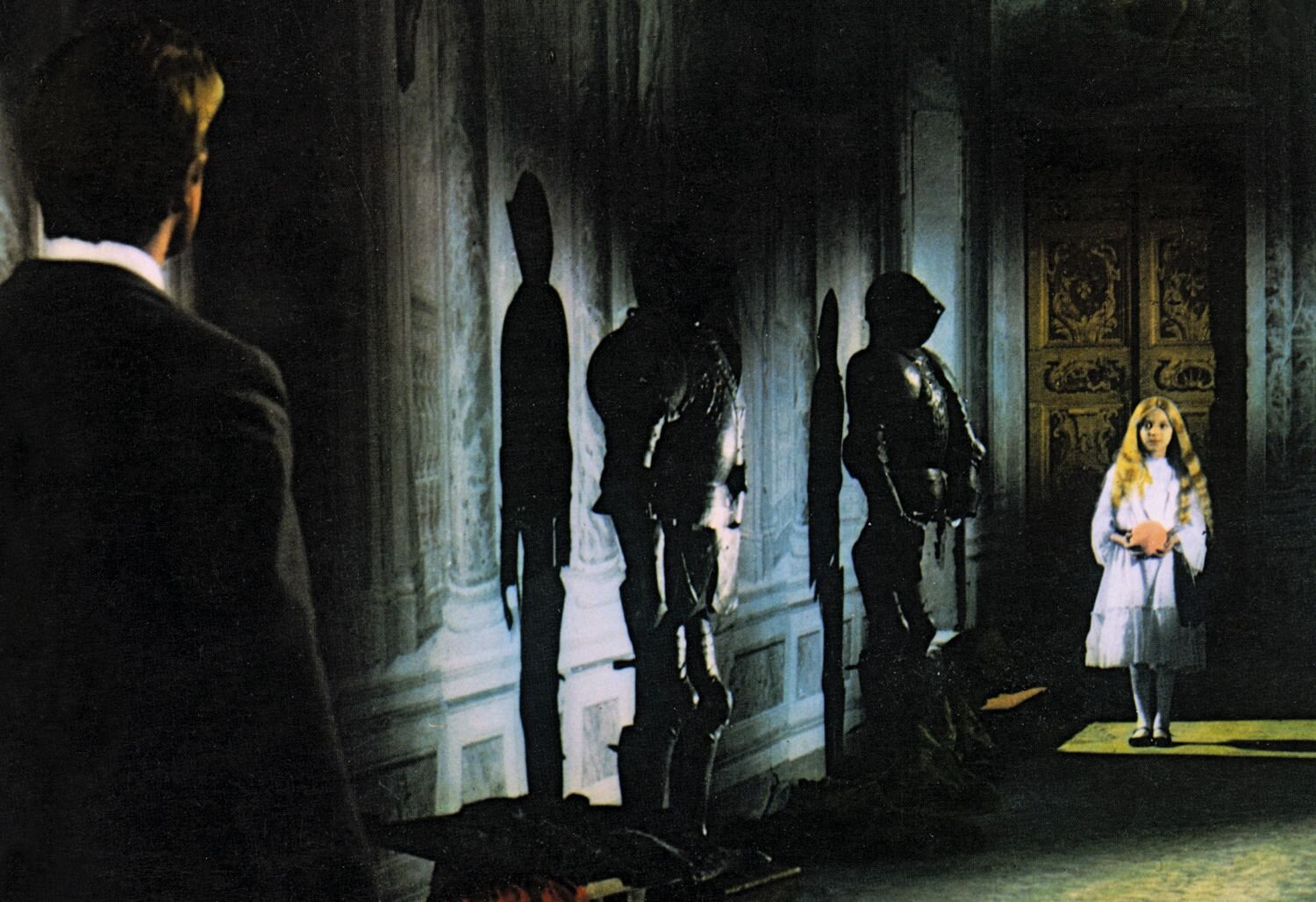

We cut to a simultaneous track and zoom, which occur at different rhythms creating a very awkward movement - as often happens to beginning filmmakers who don't have a handle on how to use their equipment. Fellini beautifully mimics every sort of technical mishandling to great effect. We see a little girl holding a white ball. The soundtrack is suddenly turned off, isolating this image from the rest of the film. Her face is theatrically painted with white make-up and there is a very bright spotlight that shines directly on her eyes making them appear bloodshot. She wears lipstick and her face suggests an adult sense of corruption. Her meticulous Victorian clothes come from Poe’s time and suggest the duality of innocence and corruption, sexuality and madness that is found in the Gothic sensibility of that time - a sensibility of which Poe was a master. Her make-up and the malevolent expression on her face come from the iconography of Romantic painting depicting evil incarnate in human form: Fuseli, Bocklin and Goya all have done versions of malevolence and death personified by a specter. Because of the intense light and the seamless background it is clear that she is in a studio interior, yet in the following medium shot we see that she is standing in the lobby of the airport we saw earlier- now strangely deserted. The white ball bounces the wrong way on the escalator in slow motion. At the top of the escalator, as in the beginning of the film, is Toby shot from below through an orange filter. We see him bowing to her, the acknowledgement of a Restoration dandy - it is the formal gesture of a gentleman greeting a familiar nemesis.

"To me she looks like a little girl."

Toby Dammit The formal gesture of a Restoration dandy meeting a familiar nemesis. Notice the dramatic expressionist lighting on the ceiling that is inconsistent with the interior of an airport, but appropriate for Shakespeare - or Poe.

Toby Dammit The empty space on the right is both deep, as if looking into a fog, and completely flat. The world is reduced to a very small, narrow stage that is creepy and absurd.

There is simulated laughter and applause. Toby turns his back to the television camera and the photographic collage of him has been removed to reveal another adjoining stage for a commercial. It is the set of a modern kitchen where there is a model wearing an apron and holding a mop as if to clean a perfectly polished floor. Nino Rota brilliantly mimics the banal happy music of a commercial as she turns her head mechanically towards Toby who whispers to her:

"Will you marry me?"

"I want to make order - I want to clean." says Claudia in 8 1/2. In Toby Dammit, six years after that film, this domestic sensibility has a different meaning. It is as if Fellini wished to perform a taxidermy on the previous character and place it in a television studio to sell soap, to show this image debased and corrupt, but with its archetypal power still mysterious and intact. So much so that Toby asks the model to marry him. There is a reaction close-up of the model who has suddenly been transformed into a plastic mannequin. She begins to rotate in place anticipating the doll in Casanova. Toby's ironic smile tells us that he is fully aware of his absurdly rhetorical question. It is at that point that he turns away from the television announcer in front of him and the mannequin behind him, and whispers the most significant lines in the film to himself:

"What a waste!"

Toby Dammit Toby caught in the web of spectacle.

Kill Baby Kill! (1966) Mario Bava’s brilliant film uses the classical elements of the gothic fairytale to create a sense of dread through lighting and blocking. Set in the 19th century the film uses various periods from the past - from medieval to Renaissance to 18th century Neoclassical - to create a sense that the past and the present are permeable and coetaneous.

KILL BABY KILL!

While the film’s exuberant theatrics were already a significant part of Fellini’s work, from Juliet of The Spirits onward, Toby Dammit borrows from the Hammer Studios in England - particularly the work of Terence Fisher - such as Dracula Prince of Darkness (1966). Fisher’s blend of fairytale-mythic elements with gothic-supernatural material made him the ideal person to helm the Hammer Studios Dracula and Frankenstein franchises. The tension in his work between sexuality and reason, and the persistent charm and sensuality of evil hint at a profoundly conservative Christian outlook reminiscent of T.S. Eliot’s melancholic and fatalistic late work. Fisher’s garish sets, always wet and dangerous, were informed by the British theater as much as by German expressionist cinema. Fellini beautifully transferred that sensibility, from Jack the Ripper’s London, to contemporary Rome. But the most obvious and clear influence on the film is Mario Bava’s superb Kill Baby Kill! (1966). Set in the late 19th century but using the actual medieval Italian town of Calcata, Bava brilliantly used the towns many layers of ruins - from medieval to Renaissance to 18th Century to great effect. Calcata seems to be crumbling into decay sometimes leaving only an arch or a freestanding wall to suggest what might have been - with the cold winter air and rain pouring into the shattered windows and broken walls. He then lights the actual architecture like a set using saturated red, purple and green gels. Bava had started as a cinematographer during the era of Neorealism and he uses that talent in a very different manner in his film, that owes much to the Hammer Studios but goes further by being grounded in an actual medieval location. The centerpiece of the film’s script is a little girl who has been dead twenty years who lives in the nearby castle - accidentally killed by careless drunken townspeople - she, or her psychotic mother who was driven mad by her tragic killing - brings death and destruction to the townspeople who accept their fate as a curse they must bear. The mother surrounds herself with creepy dolls that once belonged to the little girl and now seem like haunted automatons - the girl also carries with her a white ball as she wanders the nighttime medieval world bringing with her a fog that permeates the town like a shroud. It is her sister, now a young woman - in effect her double - that finally brings redemption and a coda to the suffering with the help of a gypsy “seer” who sacrifices herself to finally bring the curse to and end.

THE DOUBLE

The sexualized doll was first seen as a subject of fiction in The Sandman written by Poe's contemporary E.T.A. Hoffman. This short story features a female automaton that sometime later became Freud's first example of "the uncanny," which he defined as “the name for everything that ought to have remained secret and hidden but has come to light”. In the 1920's The Sandman inspired various filmmakers, writers and artists to deal with that aspect of the story that centers on the mechanized sexuality of the automaton - most spectacularly perhaps in Fritz Lang's Metropolis. This was a way to articulate the dysfunctional sexuality that seemed contiguous to the speed and corruption of contemporary metropolitan life. Among the most brilliant examples aside from Lang's masterpiece are George Grosz's drawings of prostitutes as mechanized dolls. Surrealist artists and writers were also influenced in the 1930's, when the mannequin (suggestively dressed and posed to presumably shock the middle classes) became a required motif in Surrealist expositions. Of more lasting interest are Andre Breton’s Nadja, and Hans Bellmer’s tinted black and white photographs of doll parts in various poses suggesting a macabre sexuality. To emphasize the presence of the automaton Toby is introduced to his screen "double" - a handsome actor with dyed blonde hair, already in costume as a cowboy but with a Mexican sombrero that he passes to Toby, to have some pictures made with the star for his portfolio. The double is at the heart of the romantic enterprise, from E.T.A. Hoffman, to Maupassant's Horla, to Poe's own William Wilson; or Adalbert von Chamisso's Apparition, from the same period, in which an alcoholic poet comes home to his small apartment from a party to see his double has taken his place. After questioning him he concludes - in the spirit of Borges a century later - that his double is the real Chamisso and he leaves to walk the streets, homeless, without a name, destroyed. This is the fate of all romantic heroes - to fundamentally arrange their own destruction because that is how the world is understood - through failure. Everyone in some sense fails, but the romantic hero italicizes it and thereby experiences his failure more profoundly - or at least he or she thinks she does. It is with this sense of heightened emotional sensitivity, of nerves on edge, of raw unfiltered emotions, that Toby Dammit confronts the modern world - or what McLuhan described as an "electronic brain" - head on, come what may.

Toby Dammit At the awards ceremony the sense of malevolence and dread in the lighting from underneath anticipates Kubrick's The Shinning.

SIGNIFYING NOTHING

The awards' ceremony that follows is held in an artificial cavern that seems to serve as a night- club, a fashion runway, and a theater. In this instance it seems to be providing a variety show but the spectacles on display seem to have no reason for being except to create spectacle itself - the sense of futility is palpable - as if it were to suddenly stop the whole edifice would collapse. This is the world of Adolfo Bioy Casares' The Invention of Morel where the spectacle of the party is simply repeated, reductio ad absurdum, because that is all the characters know how to do. In short the sense of spectacle and adulation are already on life-support. The catastrophic failures of the utopian societies of the post-war era have long lost any credibility or even desirability, but nothing has come along to replace them but a massive entertainment culture - what was termed "The Society of the Spectacle" by Guy Debord - that we are still experiencing today in a more pernicious and pervasive way because of the facility of portable devices that allow us to carry that culture, literally, in our back pocket. More problematically, that culture, as McLuhan pointed out, is intrinsically a part of our being - or as he so succinctly put it "Big Brother goes inside." In effect media become an extension of the human nervous system and vice versa. Wielding total power the media elite come to celebrate themselves - and their pyrrhic victory. Fellini brilliantly mimics the false enthusiasm and mannered bravura of the awards ceremony - along with their unintentionally funny conventions with regard to shot selection - to highlight the fatuousness and boredom of the players dressed in glitter and gold. This is a world of elites congratulating themselves at the feast - a party in their own honor - but even they seem to sense it is absurd and pathetic.

Toby Dammit has climbed to the top of that community - the world of media - and his sense of self-loathing is surely a way of trying to understand that culture through his own body and its response to it - and that is a classic actor's approach. The fact that he is destroying himself in the process is crucial in understanding the moral effects of that civilization, as Toby Dammit embodies the promise of the ludic itself - of eternal youth (or adolescence) - this is one of the most deceptive strategies in a society of control; the fatally seductive idea that fame and wealth can confer a libidinal space of unrestricted self-creation under the aegis of play and pleasure. Toby Dammit goes to that place and what he finds is a trap with no exit behind him and a very narrow road out - with a little girl from the 19th century carrying a white ball waiting for him. The uncanny returns - in the form of innocence lost in the Victorian era - the age that perfected the machines that would fix time and space and reproduce it on a piece of glass or paper and eventually on a screen - the form we know today. Toby Dammit does not narrate the uncanny, or the fantastic - as did Poe himself - but makes present, or simulates it as a specter from the past - a ghost that will not die - and one that is not bound by the rules of Freud's highly rational analysis of "The Uncanny," or Lacan's writings that squared Freud's texts for a more controlled, digitized society. This ghost is a loose cannon that comes armed with a smile and a harmless toy - and she spells doom. It's endgame. Done. Jim Morrison and The Doors said it succinctly: "No one here gets out alive."

Toby is led to a waiting area and made to sit and when he asks for a drink he is told "no" with a disapproving parental shrug. Toby is treated as if he were a child throughout the film because despite Toby's associations with drinking, speed and abandon he is essentially a passive character. He slouches like a bored adolescent in the limousine while the realities of the city pass before him; he sits in the television station answering questions like a spoiled child, at one point sticking his tongue out at his interviewer; he passes the award's ceremony barely conscious, in an alcoholic haze, sleeping in his chair. Toby Dammit's character is further revealed in T.S. Eliot's study of Poe that defines him as "irresponsible and immature...with the intellect of a highly gifted young person before puberty. All of his ideas seem to be entertained rather than believed."2 Eliot's acerbic condemnation of Poe seems to fit the character of Toby Dammit far better than the master who wrote The Fall of the House of Usher. As Ray Charles' classic song Ruby plays on the soundtrack a woman who is beautiful in the traditional manner of a successful model/actress, comes and sits at Toby's side whispering seductively:

"I am the one you have always been waiting for…we shall have a perfect life together…you will never be alone again!"

Toby Dammit A spectacle without a reason for being except to create spectacle - this is the the world of Adolfo Bioy Casares' The Invention of Morel where the spectacle is simply repeated indefinitely because that is all the characters know how to do.

Toby Dammit "You will never be alone again!" The most extreme close-up in the film is probably a fantasy image, but we cannot be sure.

The band strikes up an uplifting introduction number as a harsh white spotlight finds Toby slumped sleeping in his chair, suggesting that the woman was a dream. He gets up and forces a grotesque smile to the cameras and the fans as he stumbles to the stage. An announcer announces with dramatic flare common to television spectacle:

"Toby Dammit! Not only a great star but a great actor!"

Everyone kisses him to bits. This is the "love" of the public turned into a musical cue - into a sonic shroud that Toby cannot escape from so he smiles back as if already halfway into his own grave. From loud applause there is absolute silence suggesting the audience was simulated, yet we see them, silhouetted figures in the midst of smoke that seems to hang in the air - they observe Toby and wait for him to make his move. Fellini films them so they look like human predators straight out of Francis Bacon. Toby, on uncertain footing, clutches at the microphone and recites from Shakespeare's Macbeth.

"A poor player that struts and frets his our upon the stage and then is heard no more. It is a tale told by an idiot full of sound and fury..."

He forgets the end of the line: "signifying nothing" and eventually looses the thread of his thought - he begins to babble about his agent in the long tradition of actors for hire. He then mentions the beautiful woman that offered herself to him and retells the whole episode - finishing by telling her very emphatically - and the audience - that he doesn't need her, or anybody else. When the appropriate musical cue is delivered for him to leave the stage he runs from the smoky award ceremony - in a rage of disgust - to the foggy street as a mysterious figure in the night appears with the keys to a gold Ferrari - his prize for agreeing to make a Catholic Western. Toby jumps into the topless car and drives off madly into the warm Italian night as some guests helplessly call out his name for him to come back into the fold and rejoin the party. Unlike Marcello at the end La Dolce Vita, who accepts that offer and takes the job, Toby attempts to escape in his gold Ferrari.

THE MAZE OF ROME

The streets of Rome become a labyrinth – one of Dante’s rings - blurred by speed and Toby, exhilarated by it, comes to resemble the middle aged Poe, alcoholic and mad. As the lights reflected on the narrow windshield spin by the car bounces in place like a toy, and Toby's flying hair and furious shifting become a comedy of simulated forward movement - clearly the car is stationary. There is a similar shot in Stanley Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange where the point of view shot from the car turns the frame into a tunnel, into which one point perspective seems to recede endlessly into a Futurist dream of speed, power and freedom. But unlike Kubrick's film – which openly delights in the fantasy - this dream is shown to be a simulacrum - Toby is going nowhere. The shots of the car are obviously done in a studio because, despite the wind effects and the street-lights flashing by on the windshield, the overall lighting remains static and consistent. Another way that we notice that the car is not moving is that the relationship of the camera and the car is highly elaborate and precise: The camera delicately pans the metallic surface of the Ferrari, gliding over its small curved windshield. It is as if one machine (the camera) were lovingly playing with another (the car) in a macabre dance - Queen Mab in modern clothes. This is the nightmare of the contemporary condition - to be in full control at incredibly high speed (that could be fatal) - but not really moving or going anywhere at the same time - complete paralysis. This is why Fellini constantly evokes a cinematic convention (such as the "freedom of the open road") and proceeds to negate it at the same time.

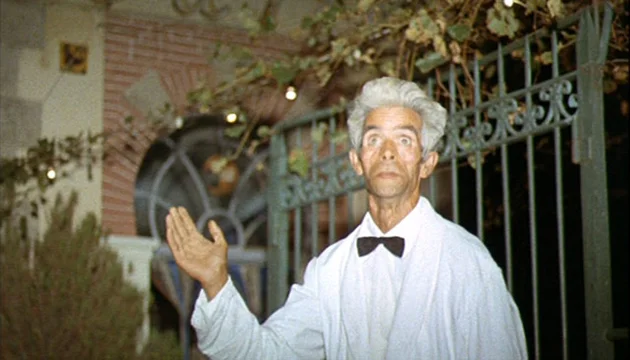

Toby Dammit A waiter seen momentarily with the lights of a moving Ferrari- is clearly real but posing as a statue or a cut-out. Strangely he also resembles a religious figure in the throws of revelation - or paralysis - but the moment of mystery has passed.

Toby drives through the maze of Rome like a man being chased by demons and in a fit of hysteria he doesn't seem to know whether to laugh or cry. Since he does not know Rome at all he improvises madly taking alleys and side streets, eventually coming to a cul-de-sac full of sheep - a beautiful symbol of Christ's fold that might have come from a neorealist film - but Toby is not impressed - the moment of mystery has passed. He puts his Ferrari in reverse and moves on, driving through neighborhoods that seem hundreds of years old and representing another age to which, clearly, he does not belong. He stops by a fountain to cool himself with some water and have a look around - then he lets out a scream of pain and disgust as loudly and as long as possible to no one in particular. There is then a short pause to see if there is a reply - there is none and he gets back into his car and drives off. The beautiful lights from a local fair or block party that is long over beautifully illuminate the gold Ferrari as it hurtles through the empty streets, and Toby clearly revels in the sense of power and freedom as he navigates the strangely deserted streets that come to resemble the metaphysical paintings of Giorgio De Chirico transported from Volos, the provincial early 20th century small town of Greece where he was born and raised, to Rome's La Dolce Vita, but the party's over, Toby is too late.

As Toby drives around a square the car's headlights illuminate a cardboard dog yet on the soundtrack we hear a real dog. Fellini shows much of the reality which Toby encounters, including people, to be props. Near a restaurant a waiter stands as if paralyzed with fear on the edge of the sidewalk. In the close-up he was clearly real - yet in a long shot we then see the Ferrari hit a mannequin dressed as the waiter and speed off. Like the actress in the cleaning commercial transformed into a mannequin the waiter becomes a life size cut-out. The fact that Toby wants to “marry” the first and that he “kills” the second is significant. Unlike Toby, who is privileged, both the housewife and the waiter are subservient figures and Toby is shown in close-up looking at them before their transformation. These close-ups strongly suggest that the metamorphosis from human to mannequins and cardboard cut-out that people and animals undergo is a product of Toby’s imagination. Through Toby’s point of view we repeatedly see adults as grotesque caricatures driven by vanity, stupidity and greed. We are made to feel that these point of view shots are an honest assessment of the contemporary world, not despite the theatrical distortions, but because of them, for it is only then that we are able to see what lies underneath the surface of reality. Fellini in a sense has it both ways. Toby’s erratic point-of-view is treated as both an alcoholic withdrawal from a reality that is out of control, and as a justified indictment of a society that is spectacularly ridiculous when we see what it prizes. Fellini started his career as a caricaturist and he uses that talent with a scathing directness that can be seen as a comic moral critique along the lines of Petronius, Rabelais and Cervantes.

Toby Dammit Great lighting focuses on the eyes as a subtle triangle of orange - the color most prominent from the airport scene - points to the face of Toby looking doomed while pinned inside his car by the narrow windshield in the front and the roll bar in the back.

Toby Dammit Toby driving full speed in his new Ferrari and remaining in the same spot without moving at the same time - the nightmare of the modern condition. Note the blackness than envelops the car is perfectly even, as it would be on a stage.

THE CRASH

At a certain point Toby finds himself in open country, outside of Rome, completely lost. He stops his car by the side of a road with a home made shack, like those made by street people. A man incongruously comes out of the shack on all fours like an animal - he is wearing a cardboard mask. Toby asks him how to get back to the center of Rome. The man informs him in Italian that the road is closed - the bridge has collapsed - but Toby doesn't speak Italian. Out of his element, he is in the wrong place at the wrong time; in classical tragedy we would say that his protective gods have deserted him. From the shielding fold of Bacchus, he is now in the hands of Mars - the god of war and agriculture. A fascinating combination that would have made perfect sense to a man of the classical age, but not to a modern, urban man - especially not one making his escape in a Ferrari. But not all roads lead to Rome - and Toby Dammit is about to find one such road that takes him to a very different place.

Toby drives like mad through empty highways as if daring an accident to happen. The crash comes against a barricade of oil drums and construction equipment. There is a shot of a tire spinning that is consciously awkward, accomplished as before, by zooming and tracking at different rhythms. Toby gets out of the car and starts to walk down a very modern highway with steel guard rails - but he appears to be in the middle of a deserted landscape. Suddenly Nino Rota’s insistent music abruptly stops. There is a heavy fog and behind the fog there are only trees and mountains. Because it is so difficult to see Toby walks into a discarded and empty oil drum lying in the middle of the road and he kicks it away - and the drum rolls into a chasm. We don't see it happen but infer it from the sound. After a few seconds we hear a very distant collision as the drum crashes at the bottom of an abyss. From the time lapse between the drum's stopping its roll and the crash we infer that it is a deep space - enough to be fatal. Only upon this realization do we see close-up of Toby smiling. He looks up and finally sees the collapsed bridge between layers of fog, and on the other side of the abyss he sees the little girl from the 19th century with her white ball. He shouts:

"I'm going to get across!"

Toby backs the car up to build up speed and with a mad laugh he slams the accelerator and goes off. We loose the car in the fog but there is no sound of a crash, as we would expect. As the camera glides to the other side of the chasm - again the marvelous machine that is the camera - not bound by gravity - we hear what sounds like a dog’s whine and see a metal wire dangling across the abyss stained with blood. The white ball bounces in slow motion into the frame as the little girl picks up Toby's decapitated head from the ground. She smiles into the camera as Nino Rota's music returns to the soundtrack. The camera backs away from the little girl. We see the highway and the collapsed bridge at dawn as the street-lights that recede into the horizon are turned off as daylight comes- but it is an artificial daylight that is as plastic and manufactured as the lights in the airport that began the film.

Toby Dammit Shot and counter shot - Toby sees his old nemesis from across an abyss - the Ferrari in the background.

Toby Dammit Shot and counter shot - the girl is enveloped in the black space of a void - the terror of nothingness.

THE LEAP OF FAITH

Toby Dammit reverses the Christ story by having Toby visited by the devil who beckons him, literally from across a divide, into entering a space that is prohibited to men. What is this space? He drives his Ferrari headlong into an abyss, yet the depth of this abyss is an imaginary space since we never actually see it. It remains shrouded in darkness and fog, a space without boundaries; its incommensurability expressing the impossibility of apprehending all with the eye or of controlling all with the intellect. This “fall” is a version, at once Christian and Modern, of the mystery of original sin. The vertigo this space creates is not caused by a fear of falling to a finite point that is fatal, but rather of falling interminably into an endless void. That is why, despite the fact that we hear the oil drum crash after a few seconds, we never hear the sound of the car crashing; that is because it never finishes falling - the cosmic and the psychic collapse into this void, an “event horizon.” This abyss disappears literally into Nature as the only element of it that we see are the craggy slopes of a mountain and the pathetic little collapsed bridge that juts out from it. The classical Romans understood this space well, and surrounded themselves with protective amulets, statues, signs and gestures to carefully protect themselves against it. They understood Nature in a way that we perhaps have lost because we mistakenly assume that we are on the verge of dominating it, or even supplanting it. No ancient, no matter how foolish or uneducated, would have made that mistake. Likewise in Toby Dammit Nature remains enigmatic, dangerous and ultimately unknowable, and man's attempts to control it (a bridge, a car) are hopelessly doomed to failure. The emphasis on one-point-perspective that Fellini rigorously returns to throughout the film is another rationalist construction helpless before the uncanny and the infinite. One point perspective, the fundamental backbone of photography and cinema - find their end in a small gap in the road - and nowhere to go but into the unknown.

Other directors, such Alfred Hitchcock also understood this terrifying space and linked it to memory and sexual desire in Vertigo; Stanley Kubrick linked it to that fatal agency of "human error," as explained by HAL, the polite and friendly on board computer in 2001: A Space Odyssey, that comes to the conclusion that humans are an obstacle to progress and discovery that must be removed, so he kills them; Michelangelo Antonioni linked this terrifying Nature to various disappearances in L'Avventura. (1961) and Blow-Up (1966). These disappearances lend these films an aspect of the occult mystery that seems to lie just below the shiny surface of the films.

Fellini reverses the "leap of faith" so crucial to the Catholic imagination from Pascal to Kierkegaard and making this leap literal - and thereby absurd. Toby puts himself in the position of using technology at its most sophisticated at that moment (a Ferrari) to attempt that “leap of faith." Yet this leap is the negative of faith; it is faith with a modern face: It is ironic, self-conscious, arrogant, contemptuous, exhausted and self-loathing. It is also doomed for it is the face of a death wish with a particular narrative in mind - of innocence lost and nothing to replace that loss but a mask. What do we call this mask? It is a mask that reflects back the original face, with all of its internal contradictions, but has not acquired sufficient autonomy to be fully self sufficient and create a new identity. It is caught in a kind of twilight zone where man's condition is just beyond his own understanding and eludes him, but he knows enough to know that the mask is only a mask. This explains our affinity, and over-reliance, on irony that has become both a defense mechanism and an axiom - the two often go together. The fact that irony is defenseless against the tragic bears repeating - and in that sense the ancients understood us perhaps better that we understand ourselves - they saw what was coming at least in a very rough outline - and that specter terrified them.

For us, as Fellini makes clear, that same specter is now behind us - it comes dressed with the garments of nostalgia. The sudden and unexplained shift from day to night at the beginning of the film is our entrance into this border zone and the return to daylight at the end is our exit cue. The strangely futuristic road ahead of us that closes the film might be the vestige of a civilization long gone, far in advance of ours, yet dead. The metal retaining walls recede into the horizon, surrounded by Nature, glowing red. The landscape is simultaneously primordial and futuristic, as if the present had vanished. It’s all as real and as deep as a classical landscape in a painting, and as flat and obviously fake as a backdrop on a set for a commercial.

Toby Dammit The ghost that will not die.

Toby Dammit final shot. One point perspective, the fundamental backbone of photography and cinema find their end in a small gap in the road, and nowhere to go but into the unknown.

1 The Annotated Tales of Edgar Allan Poe / edited by Stephen Peithman. Avenel, 1981

2 From Poe to Valery / T.S. Eliot / From: On Poetry and Poets/ Faber & Faber 1984

©George Porcari 2007