Undesirable Alien

Veronica Gonzalez

Catalog essay 2009

1993 Aventuras Con Tio Cesar #5

My life has for a long time been woven around George Porcari’s, or his around mine, I realize as I write this. It is in my calling up of memory for the writing of this piece and the corresponding implicit passing of all those moments gone that I comprehend too the ongoing motion and vital- ity of our interrelatedness. And it seems, as I write this, that language is in some ways always an elegy for and of itself. In the moment we speak: I, I is already past. It is mournful that gap, or due to be mourned. If my utterance proclaims its own passing even as I open my mouth, how much more is this passing eulogized by the written word, a film, a photograph. And how deeply felt the long ago story of our first meeting, with Steve Hanson, in the stacks of the library at Art Center College. Or that of how I met Jorge, for the first time, at George’s house; or, more than a decade later, that it was at his house again (a different place) that Jorge first asked me out on a date; or the fact that Mark and I published his first essays in what was our long ago zine, Inflatable Magazine. This after I had introduced Mark to many of my friends (including George) in the unlikely setting of Mexico City. How can I look at any of his work, or speak of the presence of the object, when what the object in and of itself most marks is a passing, a time gone, a death, a pointing away from, a not quite... not quite.... But I must admit that they, these objects, point toward as well; it is an incomplete motion, this time travel, this prodding of our past, yet the gesture is there. These questions seem central not only to our longstanding friendship but on a larger scale to the very art of George Porcari. His work appears to be involved in the pointing toward that which lies beyond it, and in this point- ing out is implied the gap, the interstice, which we as viewers try to fill, though we know that we never fully can. And so, the question remains, in his work (as in that of many others): how to consider the space between, the gap, and those things, like music, or the best writing, and art, which depend on that space: on the this to that... to that... to that. If transition, or the space between is all there is, really, then how to think about the image? Can flow and vitality have something to do with it?

There are those for whom this question of flow, of the vital, seems central, Henri Bergson helped to define this question as a question. For Bergson the interconnectedness of all things seemed the only reality, the breaking down of systems or objects into understandable and fully knowable parts (what he termed the scientific order) seemed a dark fiction indeed; for how can things be pulled out of time and known? In the moment we take things out of the vital, we are creating a fiction which we term “knowledge” or as Bergson puts it “scientific truth”. How much more real the intuitive form of knowledge he espoused, with its ultimate acknowledgement of the interconnectedness of all things, of our inability to know through a breaking down into parts. Can the story of a friendship, for example, be put down to any one event, or set of events, or relation or set of relations, is it not an organic form like any other, dependent on all that touches it, and all that is brought in?

And so, can there be an art that is not an elegy? What if instead of notions of death there is a possibility that a certain kind of art can lead us into an agreement with Bergson that knowledge is intuitive, an art which leads us to the polyphonic, to the layering of what we know, speak, see, are. Can objects and texts in fact function in this way instead, a pointing toward, a part of the motion, a presence through interconnectedness? Bahktin’s dialogic speaks to this, Kristeva’s intertextuality too. This non-idealist, non-absolutist, non-gestalt, non-object obsessed, non-privileged-moment way of viewing the world leads us instead to a view based on contingency and incompletion and process and dynamics and a moving toward. It is Bergson who helps us to wonder: what if things can not be broken up, not known in that way, what if it is as soon as we attempt to break things down into parts, into glorified objects, that we are dealing with, causing, a real death, ignoring the this to that. For, everything is connected, Bergson has reminded us, and in an attempt to really know you cannot pull things apart. Memory, which is invoked in all of our thoughts, helps our understanding of this, aids in our grasp of the vital motion ...

George Porcari’s work speaks to all of this. It is full of notions of memory – real and imagined, or fictionalized (though never contrived) - and longing, and the space between. It is de-centered, and ambiguous and seems to strike out against the final say, the complete object. When I first met George in 1985 he was making long strips of images mounted on foam core or aluminum. He is a real film buff, and this work was certainly a nod to film; the images were a succession of family snapshots, some portraits, shots of friends, film stills, found images. Through his placement, a succession, motion was inscribed into these individual shots. He moved you through them, or, rather, he allowed you to move through them, at your own pace. You might recognize a teen-age George, about to board a plane leaving Lima for Los Angeles and surrounded by little girls – his cousins there to bid farewell; those girls, of various sizes, all wore the same orange dress, white piping accentuating their arms and chests, the soon to be forever altered George standing bravely alongside them in his stoic good-bye stance. You might recognize an obscure shot from Nosferatu, or Alice in the Cities, or Glenn Gould’s pointing hand. There’s a smiling Steve Hanson, there’s Pae White, Jorge, once or twice, there am I.

Those transitions from image to image underscore the space between, motion, vitality; the images had no easy relation so that you, as the viewer, were involved in creating the interconnectedness of it all, and you too, as the viewer, were a part of it, free to take what you would from the work. After about eight years of these long strips, sometimes with up to 50 images, George pared the work down, literally, into pairs of images. And this in a much more controlled way, of course makes us think of collage and jazz, unlikely pairings and the this to that, and of what happens to the eye and mind when presented with all of this. The jumps we make, like those of time (60 years between the images taken by his Tío Cesar and those taken by himself ) and place (the thousands of miles between Lima and Los Angeles, or Berlin and Lima - again in the Tío Cesar series) underscore all of the visual motion in those pairings.

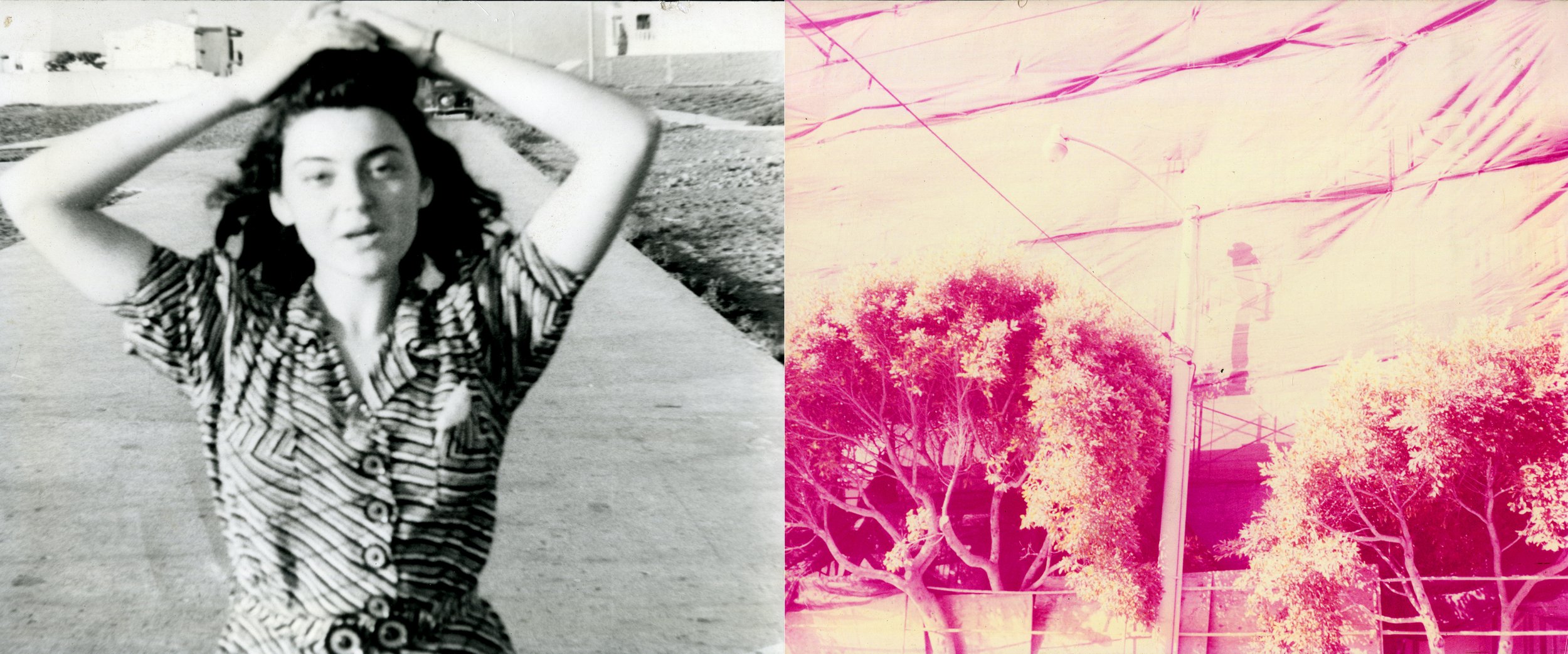

I have mentioned Tío Cesar twice now, the photographs, and so I feel I should share something about that work. Tío Cesar, George’s uncle, was a medical student in Berlin, until forced to leave there as an undesirable alien in the late 1930’s. He had a rough ride home, over the sea between, and died a year later from pneumonia contracted on that long boat journey back. The photos in this series are pictures taken by him while in Berlin, the pretty girlfriend, a love left behind (much as George would many years later leave his pretty cousins) whom none of the family ever met. Did she ever find out Cesar had died? No one knows her, ever contacted her; these photographs are all we have. George recently told me that he believes the deep melancholia which permeated his family as he was growing up was due to Cesar’s untimely death, the golden son, to be sure, and his family’s inability to ever get over that loss. Sixty years later George would have a dialogue with this long lost uncle, who had sepia colored so much of his life but whom he had never met; in those diptychs George answers his uncle’s photographs with images he has himself taken, mostly of Los Angeles – feeling half alien himself here, the immigrant with one foot in each of the Americas for his entire life. George has a great love for la jetée. I understand this love more deeply now: the undesirable, the woman left behind, the attempt to try to reach her, the photographs – for one moment instilled with life - the here but not here aspect of it all, a moving toward which can never be fulfilled.

It was after these diptychs that George moved to the single image, yet he is still able to create a motion in these single image shots, a de-centered feeling which defies the heroic he is so ardently against. He does this through his repeated use of reflection, through his cut up images; and the way that he manages to create a collage effect just by using buses, road signs, moving cars and mirrors, is quite remarkable. But there is the melancholic air of all of the subjects as well – for melancholy always points out, to something missing, so that we never get a subject completely caught up in an action, completely and fully in and of themselves – instead, in the few instances where there is a subject at all, there always seems to be a gap, the unbroachable space. The photographs do seem to mark a death, to be a sort of elegy, a mournful death poem, his uncle forever eulogized, even when there is nothing of him within the frame of the shot.

So, Steve Hanson introduced us. He and George both worked in the library at Art Center (which has become such a mythic place, so many people following in their footsteps – Diana Thater, and Giovanni Intra and Jorge, and Mark von Schlegell - whom I prodded to ask Steve for a job). Steve and I were reading incessantly in those days; there was a great used bookstore we would all go to together, and about which George has since made a film, House of Fiction. We were just taking everything in; and George was helping to contextualize; he was our informal teacher, our mad professor friend. In those days we listened to a lot of music too; Steve and I had been LA punks; we’d met several years before at a Black Flag show when I was still in high school – well, the band never showed up (they were supposed to play at his school, La Cañada High), but we were both there. By 1987 we were living together, with a painter who was a protégée of Jeremy Gilbert Rolfe’s, and we had a lot of parties. Steve’s great art band, Myther, played their first show in our living room. George was there for all of this, again, contextualizing, talking about NY in the 70s, comparing us to his friends back then. He is a great lover of jazz, and though at that point I knew nothing about that music, I would later come to understand where it meets with his love of collage, and sampling and incomplete thoughts – because incompletion seems to be the only place to leave a thought. As mentioned I met Jorge with George. I remember we were all sitting on the floor of George’s apartment and Jorge came in with my and Steve’s painter roommate. A month or so later I saw Jorge’s first show at Bliss, in the garage, which Steve and Jorge and George all helped to drywall. It was a great show – I’ve written about it elsewhere – and when I complimented Jorge on it he just kicked some pebbles around and thanked me without looking up. Nearly 15 years later it would be as we were leaving George’s house that Jorge would ask me out on our first date. I thought he was joking, we’d known each other so long at that point. Of course, it turns out he wasn’t; Penelope, our daughter, is the proof of that.

George Porcari showed work at Bliss too, the aluminum mount- ed fifty image homage to Death in Venice, simply titled Death in Venice, a piece in four or five long strips – the Visconti film with Dirk Bogarde is based on Mahler; Porcari humorously bases his Death on Stravinsky and his wife vacationing in Venice, a much lighter version of love, which George ends with a snapshot photograph of a dog he took on a beach. This exemplifies his disdain for the heroic; he is a funny flaneur, has an admiration of the space between things, of process, openness; he has a deep love of collage, is a teacher, a talker, and a great listener too.

There is, to be sure, a lot of silence with him. A lot of just observing. But when you hear a voice slightly different from the others, and interrupt to ask a question: Tell me about this woman singing, he will go on to tell you the entire history of Sathima Benjamin, her husbandDollar Brand, and her one existing recording with Brandand Duke Ellington. Or if you make a comment: I just sawNights of Cabiria for the first time, he will tell you all about how the film came about, Giulietta Masina mugging for the camera and how Fellini decided to make a film based on that. Or he will begin to speak about a beautiful poet you are both staring at in a book; and there is a love of life in this. And a generosity. A spirit that wants to give, like anyone of your favorite friends who pulls out all his records and books the moment you walk into his room. You enter a space in this way; share an interior, and this in-between space, the space which is his because he is offering it to you and yours because you are receiving and participating in it too, and neither of yours because it is shared and you are both open and offering and giving and talking. This shared space is the locus of creativity, according to the great child psychologist, D.W. Winnicott, the space in which life is lived in an active mode. The gap, the transition, the space of motion. And in becoming a participant in these open spaces an activation, which is life, occurs.

A Cloud In My Pants (this page) is a typical Porcari single image work. It is funny partially because it makes literal Mayakovsky’s earlier poetic: If you like-/ I’ll be furiously flesh elemental,/ or- changing to tones that the sunset arouses -/ if you like-/ I’ll be extraordinary gentle,/not a man, but – a cloud in trousers! In George Porcari’s version we see a car through a large plate glass window, a structural beam obstructing full view of this car and the parking lot it sits in. We see more cars and buildings across the way, and a reflection of further cars layered onto our central car. We begin to notice that our reflections have reflections, that those buildings across the way reflect other buildings, and there are one or two cars which may not be in this parking lot at all, for they may merely be reflections on further windows. The structural beam that obstructs our view is the only thing holding us up, we now see. And it comes clear to us, that on our central car, our protagonist car, there is an image of a man – chest down, his arm and hand clearly visible – our photographer perhaps? It is impossible to make out whether he is reflected on the window in front of this car, or onto the car itself; is it only one window; are there not too many reflections for one window? and we are astonished to learn that George never works with double exposures. The cloud on the windshield does, in fact, complete this man; here it’s his head it replaces not the inside of his trousers. And then we see that there are other clouds on other cars in this parking lot, perhaps completing other men. And the scene is a distinctly urban one, big sixties modernist buildings reflected in the windows of big sixties modernist buildings. The only human image: this reflection on this car, the now ubiquitous symbol of the speed which Mayakovsky celebrated so enthusiastically in his life and in his work (though here it is parked), speed now supremely privatized in the form of the personal vehicle. Man automatized. In his autobiography Mayakovsky tells us that when he first saw a rivet factory illuminated at night he “lost interest in nature. Not up to date enough.” Is this de-centered parking lot something of the modern he envisioned? But we know that he was tortured by love too. And those of us familiar with George Porcari’s work have seen clouds on windshields before, associated with speed, the urban, motion, life, but also with the vanishing face of a woman, the Talin of many of his 80s photos thus shown, the Talin of his 80s obsession, the beautiful unattainable girl whom he met wandering the stacks of the library, thus reflected more than once.

There is a sense of freedom, of life, choice, inscribed into Berg- son’s insistence that we consider the temporal, duration. George Porcari’s work provides us with a dynamic layering of information, each image pointing us in a multitude of directions, activating the space with our own memories, chance encounters (it is helpful in this vein to know that Porcari doesn’t compose his images), literary and filmic and musical references, a cacophony of images in each single shot. This vitality is often and poetically hinted at through his use of reflections, a trope he has been employing since the 1970’s. But it is also a pulling off of the melancholic, of death, the unbroachable gap, the missing person, places left, lost time and past histories, it is an insistence that the mournful is a stop, but is not a place to stop.