WHO’S THE CLOWN WITH THE CAMERA?

A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE ART OF THE PAPARAZZI

Nobody can commit photography alone.

Marshall McLuhan: The Photograph -The Brothel Without Walls

Man forgets that he produces images to find his way in the world; he now tries to find his way in images. He no longer deciphers his own images, but lives in their function. Imagination has become hallucination.

Vilem Flusser: Towards a Philosophy of Photography

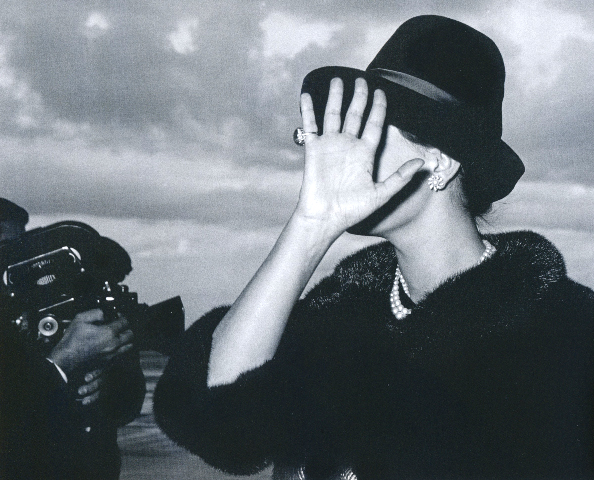

Ron Galella, Book cover: No Pictures, published 2008

1. Film Speed

Who's the clown with the camera? is a rhetorical question made by the celebrity and talk show host Johnny Carson in 1976 to another celebrity in the presence of Ron Galella, the photographer - and infamous paparazzi - taking their picture.(1) The comment was meant to be both funny and connote an allegiance between celebrities, united in the belief - so obvious that it required no answer, and none was given - that photographers were clowns. Over two decades earlier Albert Einstein, between extended stays at Princeton in the post-war era, trying to solve the riddles of the universe, had called photographers "lightmonkeys," a term then in use signifying "stupid photographer." The two statements clearly show a contempt for photographers, who are perceived to be stupid clowns. How did this situation come about? Surely they were not always considered as such. When we look at the early pioneers of photography it is a very different story: William Henry Fox Talbot (1800-1877) was thought to be a reputable scientist; Julia Margaret Cameron (1815-1879) was a visual poet admired by dignitaries from all fields; Louis Daguerre (1787-1851) was a successful artist, and one of the inventors of the diorama - a form of proto epic cinema. Where did it all go wrong? The answer can be reduced down to one word: Paparazzi. This is a brief history of their birth, the philosophy behind their aesthetic, and their rise to importance, if not prominence, within the field known as popular culture.

The reason that there are no paparazzi pictures in the 19th century is film speed. The first picture ever taken in 1826, by Joseph Niépce, required an exposure time of eight hours.(2) Early Daguerrotypes, Ambrotypes and Tintypes required an exposure time indoors of well over a minute. People who were moving in any picture simply showed up as blurs. This time frame was slowly improved over the years and by 1900 Kodak had developed the Brownie - a small portable camera - that was fast and performed magnificently in the outdoors but was useless indoors without a flash. 35mm had become the accepted film format early in the 20th century, due to its industrial production for use in motion pictures. Still photographers adopted the new 35mm standard due to its flexibility and relatively cheap cost. The main problem was that the cameras that used 35mm film in this early period were prohibitively expensive. The first professional portable camera, The American Tourist Multiple (1913) was exclusively for the rich. World War I slowed down innovations in film speeds and portable cameras, until 1925, when Ermanox and Leica both introduced affordable, small, lightweight, portable cameras with sharp lenses.(3) By then film speeds had caught up to the cameras potential and it became possible to shoot indoors without a flash with a very small camera that was easily concealed.

Erich Salomon, Conference at The Hague, 1928

2. Erich Salomon

The photographer Erich Salomon (1886-1944) at the age of 41 was the first person to have the ingenious idea of making a hole in his hat and hiding a camera inside. Trained as a lawyer and educated in the classical German humanist tradition in the early 1920’s Salomon, who insisted on being called “Herr Doktor,” could mingle with diplomats and politicians with ease. Aside from his hat, he often hid his camera inside his coat or his briefcase taking it out for the moment of the shot and then casually placing it back into hiding.(4) The loud shutter noise of the Ermanox was covered by a cough, or the sound of a briefcase opening. Blending in without difficulty Salomon was there when politicians, in a lull between wars, were debating the new world order over coffee and cigars. When an aristocrat or politician was absent from the proceedings Salomon would take his chair and blend into the surroundings.(4) When the Pact of Paris was signed in 1928 by all of the heads of state that had participated in WWI, presumably ensuring that such a tragic and useless war on a mass scale would never happen again, Salomon was there taking pictures with his hidden camera.(5)

Erich Salomon, Conference at The Hague, 1930

Upon seeing the images that Salomon had caught unawares, the then foreign minister of France Aristide Briand called Salomon the “king of indiscretion”.(6) This banal description unwittingly tells us a great deal for it shows clearly that Briand accepted the idea that journalists, and now photo-journalists, would be discrete as a matter of course. Salomon had betrayed a trust and broken a convention. His photographs were slightly soft on focus and the angles were sometimes awkward – conventions that we have now come to expect from paparazzi photography, but were then new and unusual. The results were immediately felt. Photojournalism of a more predatory kind quickly became an established norm and the resulting work became a part of the official historical record. Salomon’s tenure as a premier photojournalist was short lived due to the war that came, despite the treaty. He died in Auschwitz in 1944.

Salomon had irrevocably changed the nature of the relationship between subject and photographer by helping to create a field of photojournalism that took pictures of people surreptitiously. There was a market for these images that was lucrative and the images were relatively easy to take with little investment, so others followed Solomon into the business. The politicians and the elites, who were often the subjects of the new photography, responded in kind. To mitigate and control the taking of pictures the “press area” was formed and politicians discovered the photo-op. Photographers were soon being used for propaganda, sometimes overtly and at others subtly, in exchange for sellable shots. An unspoken contract was established between subject and photographer, and it remains that way to this day.

In the 1930’s Walter Winchell, an American newspaperman, radio commentator, and astute self-promoter, revolutionized journalism by inaugurating a much more aggressive and virulent form of news in the New York Daily Mirror that catered to the lowest common denominator emphasizing gossip, violence, sexual transgressions, and domestic dramas concerning politicians, their friends and lovers, and the rich and famous. Neal Galber, Winchell’s biographer: “In 1925, at a time when the editors of most newspapers were reluctant to publish even something as inoffensive as the notice of an impending birth for fear of crossing the boundaries of good taste, Winchell introduced a revolutionary column that reported who was romancing whom, who was cavorting with gangsters, who was ill or dying, who was suffering financial difficulties, which spouses were having affairs...”(7) Winchell’s gutter press was relentless and enormously successful. The clandestine photography of Salomon and the ethos of the new tabloid “yellow” journalism pioneered by Winchell would coincide and set the stage for era of the paparazzi.

Anonymous Photographer, Press Area, Photographers using the Speed-Graphic camera, 1943

3. The Speed Graphic Era

Salomon’s more clandestine approach ushered in a paparazzi style of photography in the 20th century that reigned from the twenties to the fifties and came to be known as the “Speed–Graphic Era”. The large and heavy Speed-Graphic camera was developed in 1912 and the film sizes varied from 2 1⁄4 inches to the more popular 4X5 inches. Each photograph had its own film sheet needing to be changed after every shot. The camera had to be focused, the shutter cocked and then released. The flash was slow to recharge from its heavy lead battery that was carried around the waist or on the shoulder. The process, if you were quick, took about six seconds.

Weegee, Corpse With Gun, 1936

Weegee, Marilyn Monroe, 1960

Despite its drawbacks the camera had two great advantages, First there was a large negative that could be radically cropped to find the kernel of the “story” and still remain sharp and without much grain; and secondly there was a blinding flash that illuminated the darkest streets, bedrooms and blind alleys. There was no place to hide from the Speed-Graphic camera. This kind of photography produced a relatively modest income but the hours were brutal, the job dangerous, and the published work remained for the most part anonymous - with the glaring exception of the brilliant self-promoter and photographer Weegee who is still the best known artist from the Speed-Graphic era. Weegee helpfully photographed one of his own paychecks in 1947: two pictures of a murdered man yielded thirty-five dollars.(8) That was a good paycheck.

Weegee literally followed ambulances and police cars to the scene of the crime trying to arrive before the competition. He photographed the dying and the dead and became familiar with every urban vice in the vicinity of New York. Weegee got close – intimacy didn’t scare him. He describes how he felt about his pictures in his classic book Naked City as follows: “There had to be a good meaty story to get the editors to buy the pictures. A truck crash with the driver trapped inside, his face a crisscross of blood...a tenement house fire with the screaming people being carried down the aerial ladder clutching their babies, dogs, cats, canaries, parrots, monkeys, and even snakes...a just-shot gangster, lying in the gutter, well-dressed in his dark suit and pearl hat, hot off the griddle, with a priest, who seemed to appear from nowhere giving him the last rites. Just-caught stick-up men, lady burglars, etc...”(9) Weegee’s prose style was a lot like his photography. While he traveled to other cities, particularly Los Angeles, to photograph films stars, New York was his town, and it was most certainly not the metropolis of conventional narratives seen in countless Hollywood films, but of brutal, chaotic confrontations ending in flashing lights from a police car and people in tears telling incoherent stories full of contradictions, digressions and dead ends. In Weege things simply don't add up - they don't make sense - the narrative line wobbles and goes south. The thriving vitality of New York was always double edged in his work and the complexity of emotions never watered down or simplified. His picture Cop Killer from 1939 is a prime example of Weegee at his best - a masterpiece of the photographic art - a film noir before film noir - that encapsulates a whole film in a single, silent, shot.

Weegee, Cop Killer, 1939

The almost laconic framing of much of Weegee’s work might give the impression that he was a detached observer – a kind of Samurai photographer who came into a dramatic scene, got his shots, and then went to a nearby bar to get a drink and have a smoke. In Hollywood films this is how he is portrayed. The reality, not surprisingly, was more complicated and interesting. Weegee (Usher Fellig) was born in the Ukraine –then a part of Austria - and emigrated to America in 1910 as a child with his parents. He left home at the age of fifteen spending his nights in Bryant Park behind the New York Public Library. As a teenager his first job was assisting a man who photographed children sitting on a pony. Many years later when he wrote a book called Camera Tips for young photographers wanting to master the medium he gave this advice: “When you find yourself beginning to feel a bond between yourself and the people you photograph, when you laugh and cry with their laughter and tears, you will know you are on the right track.”(10) At the time they were made, Weegee’s images were seen only in newspapers and tabloid journals. His style was virtually invisible to his viewers because the images were designed to be descriptive so their aesthetics – either positive or negative – were ignored. If a particular image by Weegee was beautiful or ugly, if it was overexposed due to the flash, or the framing was awkward, this was simply seen as an unintended effect due to the circumstances of the moment. What was important was that the image was real. The man lying on the street is dead, the woman staring at us out of a car window is on her way to prison for murder, etc. In the Speed-Graphic era content is all – the rest is academic.

4. The Telephoto Lens

The telephoto lens was invented by German lens manufacturers during the Second World War to be used for surveillance – specifically to survey and photograph the British coast.(11) The Germans were planning to invade and needed to find good landing sites for an amphibious attack. The telephoto lens performed magnificently, but when such an attack was finally launched in June, 1944 it was by the Americans in the beaches of Normandy. There was a young Hungarian photographer with the American Army named Erno Friedmann who had recently changed his name to Robert Capa, after his favorite American film director Frank Capra. Mr. Capa, a Jew, was determined not to end up in a death camp like his compatriot Erich Salomon, but when he landed in the beaches of Normandy he didn't have a gun, only a camera similar to Salomon’s. No telephoto lens was needed as he was already very close to the action. Yet it didn’t take long for the telephoto lens to become a part of the normal apparatus of journalists, sportsmen and voyeurs. By the 1960’s the equipment was relatively affordable due to mass production and the Japanese market. While early lenses were both heavy, cumbersome and expensive the lenses slowly became an essential arsenal for the paparazzi. All the equipment, the film speed and the business practices were solidly in place for the birth of the paparazzi by the late fifties - and this birth would occur in Rome. At first this might seem a rather odd place as most politicians of note in the postwar era were in the USA, the Soviet Union and the allied powers in Europe, most film stars were in Los Angeles, and most of the ultra rich could be found in New York or on the beaches of the French Riviera - but it is to Rome that we turn.

Pierluigi Praturlon, Anonymous photographer and Anita Ekberg on the set of La Dolce Vita, 1959

5. Fellini, Rome and the Paparazzi

What made Rome such an ideal mixture of elements is a perfect storm of economic and aesthetic confluences coming together in one place: First, Rome was cheap. Not only artists, filmmakers and musicians but writers such as Gore Vidal, Truman Capote and others moved from the USA to Rome.(12) Unlike New York it was free of the influence of Abstract Expressionism, John Cage and the new conceptual "serious" music, Hollywood blockbuster films, and the writings of the Beats - all of the major, dominant movements in art, music, film and literature in the USA. Fellini and others, working in the milieu of Cinecitta, would repeatedly make fun of this aesthetic dominance; unlike Los Angele, Rome was virtually without peer pressure despite the massive infrastructure devoted to film production at Cinecitta; Rome was seen as a backwater vacation spot where creative people felt they had nothing to lose, they could take greater risks. The feeling was that if you screwed up probably no one would notice, and if it was a success you could export your work and promote it. In short, Rome was open territory, and those kinds of places are usually fun, invigorating, creatively energized, and bound to attract all sorts of very different talents and temperaments who meet as equals, on turf that is relaxed and somewhat alcoholic and promiscuous. In effect the combination of cheap rents, and an influx of creative people, meant that individuals of vastly different cultures and classes were suddenly occupying the same spaces, sharing the same friends and lovers, the same parties and dinners, where inhibitions and social norms were relaxed and fluid - this created the ideal conditions that gave birth to the paparazzi. It also gave birth to the Italian art film, that succeeded the already lauded work of the masters of Italian Neorealism. These two very different kinds of film aesthetics would coincide in Federico Fellini's La Dolce Vita (1960) whose work straddled both worlds. Aside from Fellini this era produced masterpieces by Michelangelo Antonioni, Pier Paolo Pasolini. Liliana Cavani, Marco Ferreri, Lina Wertmuller, Marco Bellochio, Giuseppe Patroni Griffi, and Bernardo Bertolucci. It was the Renaissance again, but in cinema instead of painting and sculpture - artforms that had by 1960 atrophied and become academicized, mannered, pompous, and had lost touch with the world as-it-is. While there were some exceptions, with fine art and "serious" music, the writing was on the wall, and it was clearly the moment for the ascendancy of the art film, graphic design, television, jazz, rock music, and photography.

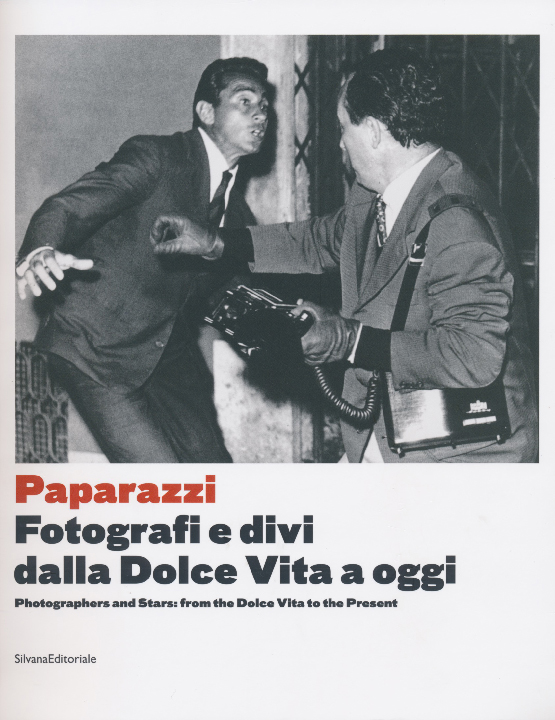

Cover to book Paparazzi Fotografi e divi dalla Dolce Vita a Oggi, Dilvana Editoriale, 2017

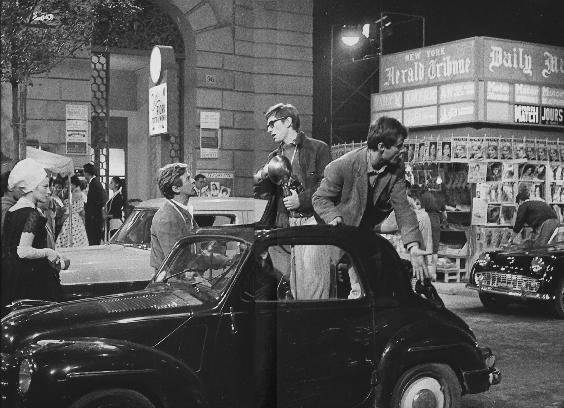

The date given for the birth of the paparazzi varies from 1949 to 1958 depending on the historian but it is definitely in the years immediately after World War II in Italy – a time of economic resurgence, wild speculative greed and struggles for a place in the post-war economic boom, that the press of the time referred to as the Italian "economic miracle."(13) Unfortunately this new wealth only touched a privileged few - as miracles often do. In the 1950's only 7.4% of the homes in Italy had electricity, drinkable water or indoor plumbing. In the south of Italy, according to a census from 1951, over 50% of the population lived off agriculture, hunting and fishing.(14) The "economic miracle" was clearly seen as a positive first step toward recovery from the devastation of Mussolini's reign and WWII, but one that affected only a few people at the top - how far it would trickle down to the middle and working classes remained to be seen. It was a period in which investors not only made fortunes but also lost them in the race to the top. A race that was well described by the Italian artists of the period - most spectacularly in novels by Carlo Emilio Gadda in That Awful Mess on the Via Merulana (1957), Alberto Moravia in The Empty Canvas (1961) and The Conformist (1951) - made into a brilliant film by Bernardo Bertolucci in 1970; and in films by Michelangelo Antonioni in La Notte (1961), Luchino Visconti with Rocco and His Brothers (1961), Pier Paolo Pasolini in Mama Roma (1962), Roberto Rossellini with Illibatezza (Virginity) 1963, and of course Federico Fellini with La Dolce Vita (1960) that created the name "paparazzi," and mythologized the profession, recreating its modus operandi in a "Via Veneto" that Fellini constructed in the studios of Cinecitta, down to a traffic jam. The real street inclined and was very short, and did now allow for long, smooth, traveling shots on a crane that could float through the space - over cars and past pedestrians, through cafes and into nightclubs. Fellini's wandering camera brilliantly articulated the new, aggressive and poetic, post-neorealist aesthetic. It is a style that would be much copied but never equaled.

Federico Fellini, La Dolce Vita, 1960

Velio Cioni, Marcello Mastroiani, Anita Ekberg and Federico Fellini on the set of La Dolce Vita, 1959

Pierluigi Praturlon, On the set of La Dolce Vita, 1959

It is Federico Fellini who invented the word “paparazzi”.(15) It happened as part of the preparation for his brilliant, episodic masterpiece La Dolce Vita. The film was ostensibly about the failure of a generation, and follows an aspiring writer, Marcello, who is unable to use the classical literature of the past, that he loves and years to use in a contemporary context, to describe the vast economic inequalities and vulgarities of the present moment - they don't seem to line up, and so he sells his talent to become a gossip reporter, and then a publicity agent. Fellini clearly uses Marcello as a sounding board to speak about a whole generation that failed to remain true to the idealistic commitments of their youth, and who consciously sold themselves to the multinational business and media conglomerates of the post-war ruling elites. As Marcello begins his tenure as a gossip reporter, in the mold of Walter WInchell, he gets a sidekick - a young man permanently on a scooter, always sitting in the back seat with both hands precariously on a 2 1/4 camera with a flash - the photographer provides the illustrations to Marcello's lurid stories. Fellini named this young photographer Paparazzo, taking the name from an Italian dialect word that means "annoying insect" - explaining in an interview with Time magazine: "Paparazzo...suggests to me a buzzing insect, hovering, darting, stinging."(16) Photographers had by 1959, when the film started production, already become more aggressive, taking greater risks as the money got better - they would shout names, usually just a first name or a wave, to get a response from their usually indifferent or defensive subjects. A certain percentage did respond, smile, and wave back, making this standard practice. The scooter was the perfect tool as the photographer could make a quick entrance and survey the field. If something interesting was happening the photographer moved fast and got his shots, then ran back to the scooter which was waiting with a co-worker ready at the throttle. They would then take off into traffic, darting between cars, or even going against traffic, making a chase impossible.

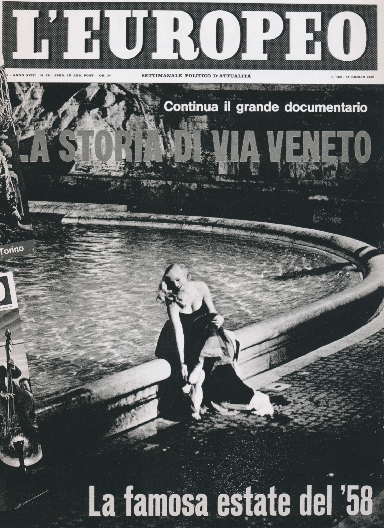

Pierluigi Praturlon, Published photograph of Anita Ekberg in L'Europeo, 1958

In 1958 Fellini had seen a photograph by the photojournalist Pierlugi Praturlon of the young Swedish actress Anita Ekberg who had presumably hurt her foot near the Trevi Fountain, and lifting up her skirt to survey the damage had fallen into the water head first exposing her magnificent figure.(17) Was the picture news? Was it a publicity stunt? Did it matter? No one seemed to know, and more importantly no one seemed to care. This ennui, this lack of feeling, this ironic, bemused indifference was new. Fellini sensed a radical re-direction of morals and manners for the postwar period in Europe that neorealism was ill equipped to deal with. Unlike the polite facades of morality and rectitude of previous generations (including those that Fellini grew up with) there was a sardonic, bemused, disregard, reminiscent of early, pre-Christian attitudes - exemplified by Petronius' "Satyricon" - a great (and very funny) literary masterpiece that would be adapted by Fellini a decade later. Fellini took the Trevi fountain incident, and, with modifications, expanded on its significance until it became the major fulcrum on which the narrative of La Dolce Vita would hang. It is one of the most brilliant set pieces in the maestro's body of work. The scene in many ways is simple. Marcello and Anita, after a long interview, and some flirting, take a road trip on Marcello's expensive sports car, and discover a street cat. As Marcello goes off to find some milk Anita wanders into the Trevi Fountain on a lark to cool off, with the water splashing on her while she wears an evening dress. Marcello returns and after a moment of reflection he realizes that he must join her in this unnamed pagan ritual, and wades into the fountain wearing a suit.

In the middle of the night, up to their waists in water Anita blesses him with some water carefully sprinkled on his head - in the spirit of the Catholic faith that permeates Rome (they have visited the Vatican earlier) but to no avail - the fountain at that very moment is shut off and Marcello is doomed. As the water is shut down Fellini brilliantly cuts from his majestic close-ups to a long shot of the couple in the water, with a pizza deliveryman on a bicycle in the foreground having stopped to observe the incredible scene. The brief shot returns us not only to "reality" but places the scene within a cinematic historical context – a privileged moment where history shifts on its axis and a new chapter begins - for it is as if the pizza delivery man was from an earlier neorealist film by Rossellini or De Sica, now teleported to the present moment, to see the end of his world and the beginning of something new, strange and powerful, but what was it? Fellini was the first to understand that the ambiguous and suggestive images by Pierluigi Praturlon, which were not taken seriously as photography or as art - then or now - were more emotionally powerful than those in the traditional entertainment media or the art world. He used the pictures to full advantage, allowing Pierluigi and his friend and fellow cameraman Velio Cioni on the set, and subsequently hiring Tazio Secchiaroli as the official photographer for his subsequent film, 8 1⁄2 (1963), that would prove to be one of his most enduring works. But just who were these young men on scooters?

20th Century Fox The Seven Year Itch Publicity photograph with Marilyn Monroe (pictured), 1954

6. Paparazzi Before Paparazzi

Before 1958 the photography of films stars and famous people was normally a very controlled affair. To some extent this is still the case when publicity departments, lawyers and agents are involved. For example, in 1954, Marilyn Monroe was photographed by a young photojournalist named George Zimbel.(18) He was one of approximately twenty photographers who had been invited to witness a scene from Billy Wilder’s The Seven Year Itch (1955) being shot on location on Lexington Avenue in New York City. It is, of course, the scene where Monroe's dress blows up from the sudden rush of air - created by a wind machine under the metal grille of a subway air vent - displaying her beautiful legs. This was an iconic moment and one that the publicity department at 20th Century Fox was determined to milk for all it was worth. Photographers got to shoot the rehearsals and Mr. Zimbel and the other photographers took as many pictures as possible. When quiet was called on the set and the photographers were told to put away their cameras, incredibly, all of them complied, except for the naive and headstrong Mr. Zimbel, who kept taking pictures.(19) For his disregard of the rules he was escorted by the New York City police from the “press area” to stand further away with the rest of the large crowd gathered on Lexington Avenue watching Ms. Monroe. Four years later Tazzio Secchiaroli and a group of young men in Rome changed all of that. Photography became open warfare with new rules of engagement, and no holds barred.

Unknown Photographer, Tazzio Secchiaroli. Secchiaroli is at the throttle of a Lambretta with Luciano Mellace behind him with a Rolleicord camera with flash. 1952

7. Tazzio Secchiaroli

Mr. Secchiaroli in the early fifties was one of many photographers in Italy who made a meager living by photographing tourists in front of landmark ruins in Rome. When they were lucky a publicity agent would call them and get them a paying job photographing a film star arriving at the airport, having dinner in one of the new fashionable supper clubs along the Via Veneto, or giving a press conference announcing a new film.(20) Secchiaroli was a go-getter and he hustled business along with other young photographers on the make going where the rich and famous went - usually following on their scooters. In 1955 Secchiaroli along with Sergio Spinelli founded the Roma Press Agency to secure a greater share of the profits. Spinelli worked during the day in the small rented apartment and handled the business end while Secchiaroli worked at night shooting and developing the shots, then printing them in the kitchen. Within two years they hired two more photographers Velio Cioni and Giovanni Lentini. Sometimes the photography business was not so lucrative, as occasionally the job was photographing a wedding or a soccer match, but Secchiaroli didn’t mind – he had worked a delivery boy at Cinecitta, and before that as a laborer in the railroads - after those experiences photography was a cinch.(20) Tourism was a growing business in Rome due to the exchange rate that favored Americans. Due to low overhead a lot of Hollywood production moved to Cinecitta, just outside of Rome, along with radical independent filmmakers such as Pier Paolo Pasolini, who took full advantage of Cinecitta in his masterpiece La Ricotta (1963). Both groups of filmmakers often times used the same technicians, crews and sets – something difficult to imagine now. In short the capital of the film world, for a time, moved from Los Angeles to what became known as “Hollywood on the Tiber.”

Anonymous Photographer, Lisette Model. The great Austrian born American photographer, showing the proper use of a Rolleiflex with flash attachment, 1952

Secchiarolli and the paparazzi used a 21⁄4” roll camera with a detachable flash. The most popular because they were the most affordable were the Rolleiflex and the Rolleicord. The negative size was large enough to wield enough information even if radically cropped, but far more flexible than the slow and cumbersome Speed-Graphic. The roll of film allowed several shots to be taken in a matter of seconds and the new fast film stocks allowed for a narrow aperture creating a wide of depth of field, meaning that focus need not be precise, but could be calculated approximately and the photograph would be sharp. The flash was detachable and could be aimed separately from the camera - one hand on the camera, the other on the flash - giving more flexibility and subtlety to the flash than it had ever had before (or has had since). Shots could even be taken at night in total darkness with little blurring and sharp focus. The only disadvantage the camera had was that it was not adaptable with the new long telephoto lenses coming into the market, which were made for 35mm cameras. These would eventually become the primary tool of the paparazzi. The new young photographers shared with Weegee a taste for the vitality and chance encounters that were part of urban life – what they did not share was a sense of empathy. Having been trained by photographing tourists and predatory, aspiring, film stars they developed a thick skin and a cynical detachment from their subjects whom they considered prey - more to the point prey that was in on the game so there was no need to feel guilty as everyone was a player. The stage was set.

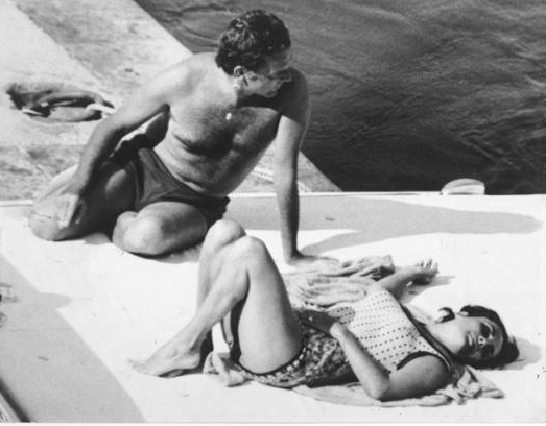

Unknown photographer, Roberto Rossellini and Ingrid Bergman, 1949

7. The Birth of the Paparazzi

The story, now legend, of the beginning of the paparazzi outlined here has been told often enough from different perspectives so that we know the events happened. What remains under debate is why it happened at all since photographers shooting film stars were well known in all of the capitals frequented by the famous since the early part of the 20th century – particularly once newspapers started to pay more money in the 1930’s thanks to the success of Walter Winchell’s tabloid press and the many imitators that followed. Photographers had also been getting progressively more aggressive, especially since the affair between Roberto Rossellini and Ingrid Bergman, in 1949, incited a public outcry (in the USA) and a curiosity among the world public, particularly in Italy, for more images. The Hollywood star of Casablanca (1942) and the Italian director of Rome, Open City (1945) were together to make Stromboli (1950) one of the great post-war European films, but the affair between them was being discussed in the tabloid press on a regular basis creating enormous pressure on the couple. The photography historian Diego Mormorio counts that year (1949) as the beginning of the paparazzi,(22)

The author Karen Pinkus counts the year of the infamous Montesi trial and its convoluted aftermath (1954), that laid open the profound social disparity of the "economic miracle" as the birth year for the paparazzi.(23) In the Montesi trial a young, beautiful, aspiring actress was found dead on a beach near the summer homes of several very wealthy businessmen and politicians who had notorious parties where women were often beaten. The story of the working class girl who wanted to cross social boundaries using her sex appeal, only to end up face down on a beach dead, created a sensation. The story combined class and sexual warfare into one headline, made for the tabloids. Photographers waited outside homes and offices assaulting possible witnesses - guilty or not - with flashes from their cameras. The Montesi trial predictably ended with a hung jury - the wealthy elite had excellent lawyers and money to spend on protecting their closed society. It all came to nothing.

Tazzio Secchiaroli, Witness at the Montessi Trial is Escorted to a Waiting Car, 1957

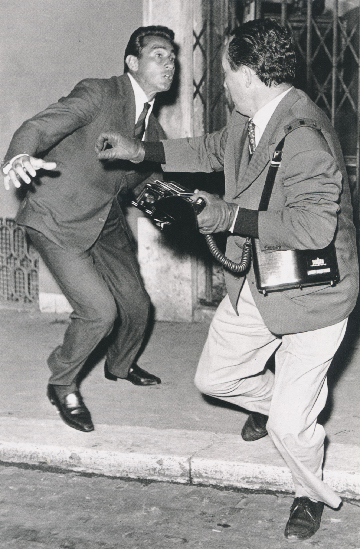

Elio Sorci, Tazio Secchiaroli on the right defends himself from Walter Chiari, 1958

Secchiaroli insisted the year of birth for the paparazzi was 1958 when he was involved in various encounters with celebrity culture.(24) What is more likely is that photographers began to move in the direction of the paparazzi style as early as the 1940’s, but it did not reach the public consciousness, and the tabloid press, until 1958, once Secchiaroli set a new precedent for staging scenes, and new price guidelines for pictures that told a story. On the evening of the 14th of August 1958 Secchiaroli along with Pierlugi Praturlon, Uberto Guidotte and Giancarlo Bonora were taking their usual tourist shots on the Via Veneto. At the Café de Paris the deposed “King” Farouk I of Egypt – then one of the wealthiest men in the world was also in Rome dining with three friends. The deposed king was a notorious playboy and spendthrift who wielded no power and had created nothing remotely notable, but there was something iconic about his dissipated mediocrity, his massive weight gain over the years from slim playboy to obese giant, as well as his outrageously sumptuous lifestyle: buying expensive cars and then discarding them immediately because they were boring, building exotic mansions that he didn’t have time to live in, etc. That he would be of interest to journalists is normal, but photographers were supposed to understand the rules: that there is an invisible barrier between royalty (of any sort) and mere subjects – to say nothing of a “news-hound” (a dog). What Secchiaroli did was to destroy that barrier. He confronted Farouk mid-meal and took pictures of him and his companions with no announcement and no warning of any kind - he simply stepped up and started to shoot setting off his flash in Farouk’s face. The deposed king became enraged and attacked the photographer physically. The younger and lighter man easily got free, running to his scooter, where Secchiaroli and his companions moved on to find new game.

That same evening the paparazzi, in their Vespas and Lambrettas, moved to Bricktop’s. This was the legendary American nightclub where Humphrey Bogart, Lauren Bacall, Ernest Hemingway and his wife Mary Welsh drank elbow to elbow in the small bistro/nightclub. John Steinbeck had once been thrown out for unruly behavior from the original club in Paris called Chez Bricktops, founded by Ada Smith. Her red hair earned her that nickname when she was growing up in a poor, black, neighborhood in Chicago during the 1920’s, and it stuck. Cole Porter wrote the song Miss Otis Regrets for her. On that night Ava Gardner - then one of the most beautiful and highly paid film stars in Hollywood - and the young, handsome, Italian-American actor Anthony Franciosa were found at Brick Topo - as the Romans called it - engaged in a shouting match.(25) They were clearly a couple in the midst of a ferocious argument. Mr. Franciosa was married at the time to another American actress, and pictures of him partying with the notoriously hard drinking and free spirited Ms. Gardner, who had only recently divorced Frank Sinatra, would not have gone down well back home. They were completely caught off guard by the young paparazzi who descended on them with flashing cameras led by Secchiaroli. To the consternation of the stars when they defended themselves from the photographers by pushing them off the paparazzi allowed one of their own to be physically confronted while the other paparazzi continued taking pictures of the photographer being brutalized by Franciosa - in effect staging the scene. As Secchiaroli put it: “One photographer would take the pictures and the other takes pictures of the other photographer fighting to take the picture”.(26) This was something new. The paparazzi were now in control of a narrative.

The next day the photographers had sold their pictures for more money than they had ever made in their lifetimes, and in the process they had invented a new profession. Secchiaroli: “ We found that with small events, created on purpose, we could earn 200,000.00 Lira while before we got 3,000.00 if we were lucky.”(27) The Italian newspaper Il Giorno carried it on the front page: “Photographer Attacked by Farouk and Franciosa.” The photography historian Diego Mormorio identifies this as the story that initiated Secchiaroli’s rise to fame. The same magazine a few days later ran the story again with more images: “Caddiatori di Teste a Colpi d’Obiettivo” or “Lens Shooting Head-Hunters.” The drama moves from the “terrible night on the Via Veneto” to the photographers themselves as the major players in the story.

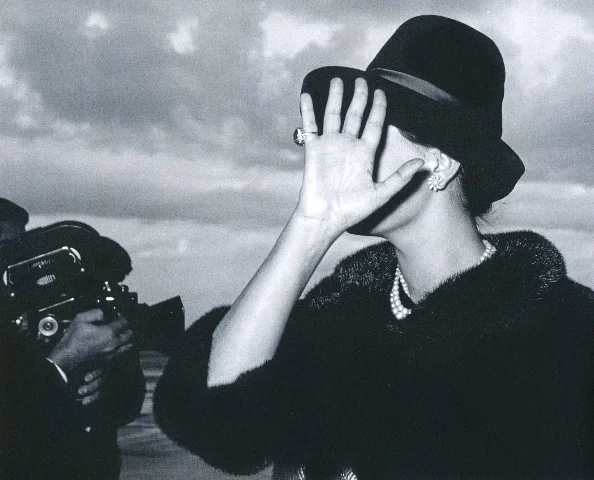

But there were problems - the primary one being that the images taken were not particularly good. Even worse they were not readable as a narrative that told a coherent story – something essential for paparazzi photography. Secchiaroli had learned from his only real teacher Adolfo Porry-Pastorel that a photograph shouldn’t need a caption. Everything in it should be unmistakably clear on first reading. Instead the images were, as Secchiaroli himself put it: an “incoherent bunch of lackluster, out-of-focus photographs.”(28) The drama they had created had sold the pictures but they needed to find a way to get more coherent shots. The paparazzi would learn from this mistake and not repeat it. A short time later, they got another opportunity with Anita Ekberg – a favorite target of photographers because of her sense of drama, her animated facial expressiveness, her pale skin, and her magnificent mane of blonde hair - all elements that were made for the cinema - and for photography.

Tazio Secchiaroli, Photographer and Anthony Steel, 1958

That same summer of 1958 Anita Ekberg, a Swedish model who had become an actress and gone to Hollywood and had found success, and her husband Anthony Steel, then a famous actor working regularly at Cinecitta, were leaving the Vecchia Roma (a popular nightclub) late in the evening and the paparazzi were waiting. From Carol Squiers interview with Secchiaroli: “...the scene looked like something out of De Chirico: just one policeman, the driver, another photographer and me.”(29) The paparazzi were aggressively confronting the couple, taunting, Steel, waiting for something to happen. Ekberg reasonably tried to move her husband to the car and drive away as quickly as possible while Steel went after the young man with the Rolleicord, flashing his clenched fists. In the struggle Secchiaroli took a magnificent shot of Steel moving across the street toward the photographer ready for a fight. Photographer and Anthony Steel, 1958 is the first masterpiece of paparazzi photography. The white line of the road creates a dreamlike vertical shape, almost like a plinth, holding Steel frozen in space. The lights above him seem like suspended white ellipses in space while Steel is beautifully backlit as if he were on display, his classical running stance caught at just the right moment as he turns toward his enemy for a confrontation. Steel’s aggressive hands and posture play off against the paparazzi moving away from him – the round flash of the photographers camera mirroring the lights dramatically poised over Steel as if he were on stage.

Tazio Secchiaroli, Anthony Steel and Anita Ekberg, 1958

Carol Squiers expresses some concerns and doubts: “Clearly, the paparazzi myth began to form around the stories of the photographers’ encounters, rather than any shocking, titillating, or otherwise remarkable photographs. This is weirdly ironic in that paparazzi images ostensibly serve as visual evidence for a public hunger to see verification of the vulnerability, bad judgment, or outright adultery of the stars. Despite the absence of compelling photos...that August night was a “eureka” moment for the photographers and the press outlets that bought their pictures.”(30) Ms. Squiers’ mystification as to the impact of what she considers unremarkable images tries to find a possible solution in the unlikely alliance between the paparazzi and leftist Italian critics of American imperial and economic power, symbolized most blatantly in the popular imagination by pampered American film stars. Could the paparazzi be somehow aligned politically with leftist neorealist works like Giuseppe De Santis’ celebrated film Bitter Rice (1948)? The question is left hanging. Secchiaroli tries to explain the paparazzi himself in an interview from the “eureka” year of 1958. “Nothing will stop us, not even if it means overturning tables and waiters, or raising shrieks from an old lady...even if the police intervene or we chase the subject all night long, we won’t let go, we’ll fight with flashes, we’ll help each other out...The increasingly ruthless competition means we can’t afford to be delicate; our duties, or responsibilities as picture-hunters, always on the lookout...”(31)

Ms. Squires response to this remarkable quote is: “... laughably inflated rhetoric for a paparazzo...”(32). Here I think Ms. Squires misses the core of Secchiaroli’s text that is, I think, very important – not so much in its content but in its tone. It is unmistakably the voice of a worker defending himself against the wealthy boss – more to the point a worker doing his job talking about rich people who want to stop him from making a living and he won’t have it (“even if the police intervene”) – and he has every intention of fighting for that job (“we’ll fight with flashes”) – not just his own but that of his comrades (“we’ll help each other out”). This wasn’t just a statement of job requirements and duties, it was an impromptu manifesto, and its principal rhetorical method was to clearly demarcate the lines of battle: the photographers and stars were the principal antagonists and it was a battle for survival. The photograph of Anthony Steel going after a photographer nails that theme. This is why the images were so compelling: they visually articulated the Post-War secret war that had remained in the background behind the Cold War, that is, the brutal class wars that dominated post war life in Europe. Secchiaroli’s image literally shows a wealthy and spoiled member of the ruling classes about to beat a worker. The class war that the media was so careful to ignore - because the press was primarily owned by corporate interests - was suddenly made dramatically visible, and poignant, in the form of a drama that this time needed no captions.

Unknown Photographer, Elizabeth Taylor and RIchard Burton, Rome, 1964

8. The Paparazzi After Fellini

The medium of photography itself is front and center in paparazzi images because of the harsh flash, the awkward angles, the clearly visible grain from the use of fast film and the blur from the shaky camera. In the work of the paparazzi this foregrounding of the medium is not a creative decision or the exploration of a convention but rather the residue of its principal aim: to capture something uncanny in a world inhabited by Gods. “Gods” here is defined as Parker Tyler defined the film star in Magic and Myth of the Movies (1947): “the vestigial form of the pagan divinities.”(33) Tyler got Hollywood. The paparazzi also understood it, and this is why their photography is almost always more interesting than the fine art photography we see in galleries and museums, that also tends to foreground the medium. The former is visceral and on the make (which is always interesting) while the latter is detached and intellectually above the action, explaining the historical context like a professor in front of a blackboard, or worse, like a politician on a soap box. In paparazzi photography the medium is not treated historically or in any sense academically as the aesthetics are merely a means to an end. This is why the work of the paparazzi, when seen as a “body of work,” tends to be extremely uneven at best. Formal concerns, which we naturally bring to any body of work, are not important to paparazzi photography because that is not the primary goal, which is to get the shot that tells the story people want to see - the shot that nails the emotions of the mise-en-scene. In that sense paparazzi photography is fundamentally illustrative.

Secchiroli’s biographer Diego Mormorio: “...the idea spread among those in the entertainment world that to challenge the photographer’s gaze – even to pretend to do so – was to create an episode that very likely would end up in the newspapers, adding to their celebrity. Some stars even informed a photographer of their movements ahead of time, so they could be sure to be "surprised" when one came upon them. Thus, a considerable number of the so-called paparazzate (confrontations between celebrities and paparazzi) were in fact setups, performances on the part of both photographers and celebrities. Contrary to what has often been said, therefore, what distinguished the paparazzi was not that they invented a photography of societal scandal, but that they introduced a methodological variation into it by creating a drama. By transforming the photographic moment into a kind of provocation, they also transformed it into what was really self-presentation”.(34) The paparazzi in a sense became artists using performance, provocation and photography - they had intuitively discovered the photographic space between presentation and representation, between reality and the Real - that was something that artists, poets and philosophers were also dealing with in their work. In effect paparazzi photography obsessively focused on the physical, corporeal nature of reality caught on film. The intentionality of human gesture and action, or “acting” and more broadly, representation as a subject.

But being a purely illustrative artform the paparazzi were unable to move their photography beyond their own very narrow range of concerns. Without a commitment to the exploration of the real world, a search through the various formal qualities of the medium itself, or any sense of historical perspective with which to build from, there was nowhere for the paparazzi to go except in the direction dictated by financial considerations. In a sense the paparazzi were finished just as they were getting started. But these are philosophical considerations - from a business perspective the paparazzi's prospects increased exponentially over time, to the point that some photographers eventually became as wealthy as the stars that they hunted.

Agenzia Dufoto, Sophia Loren at the Airport, 1961

9. The Sixties and Beyond

Two things happened after Tazio Secchiaroli and his friends started to make real money from their photographs of the rich and famous. The first is that the stars, realizing that they were now prey twenty four hours a day, became enraged because it meant that their personal lives were now the subject of constant surveillance for profit. They correctly assumed that if large amounts of money were involved there would be no reprieve. The second thing that happened is that a bond was made between publicity departments and paparazzi to stage events for the camera on a regular basis – as happened with Anita Ekberg and her “fall” into the Trevi fountain - but on a much larger scale. Publicity people also correctly assumed that if they threw out ten absurd propositions for “new stars” – no matter how ridiculous - at least one would take root. The stars themselves were caught between the paparazzi who wanted to record everything that would be sensational and create short term income and publicity departments who wanted to record photo-ops that would generate growth and produce long term income. The strange dance of seduction and repulsion between photographers and the famous that was the result of these contradictory needs persists to this day.

Unknown photographer, Paparazzo Rino Barillari is attacked (with an ice cream cone) by actress Sonia Romanoff, 1966

Daniel Angelli, Serge Gainsbourg and Jane Birkin, 1969

Daniel Angelli, Brigitte Bardot, 1969

Marcello Geppetti, RIchard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor, 1963

By the late sixties paparazzi photographers such as Daniel Angelli, Marcello Geppetti, Rino Barillari and Gilberto Petrucci had switched their Rolleiflex to 35mm cameras with long lenses (the type pioneered by the Germans during the war) and were shooting from great distances – sometimes from a helicopter or a speedboat, as in Geppeti's image of Brigitte Bardot sunbathing in Juan-les-Pins. Marcello Geppetti’s images of Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton, before they were officially a couple, was one of the biggest scoops of the decade.(35) The Vatican accused Taylor of “erotic vagrancy," without clearly explaining what that was. Fortunately for Ms. Taylor, whose best work was still ahead of her, any threat from the Vatican had lost its institutional power to render its victims paralyzed with fear. Since the rabid "witch trials" of the previous century, when women - particularly those who wielded any wealth or influence - were routinely tortured and burned at the stake, the office of the "inquisition" had, at most, only coercive power. The most the hapless Vatican could do in 1963 was vilify Taylor from the pulpit, write letters to the press, and complain to the local law enforcement agencies, who listened politely. The scandal that ensued made Geppetti’s images – of the couple in bathing suits casually sunbathing on a boat – a sensation that lasted for months. The amount of money to be earned from such photography was growing steadily with no ceiling in sight. The new breed of paparazzi took clandestine photos like Weegee, but unlike the Ukranian master they had no direct connection to their subjects. Weegee and the people he shot belonged to the same club; the prostitutes and the barmen are often seen giving the camera a complicit look, because they understood each other. Weegee had a job to do and so did they - it was about survival in a world of professionals.

Jean Pigozzi, Mick Jagger and French Policeman, Cannes, 2004

Jean Pigozzi John Belushi & Jean Pigozzi, 1977

10 Jean Pigozzi

With Jean Pigozzi and the younger group that came up in the sixties and seventies survival had been met and conquered – now it was about lifestyle. The star system itself became Pigozzi’s subject – most insistently in the pictures he has titled Pigozzi & Co., begun in 1972, that show him with the famous in close, intimate-for-a-second shots, taken with his extended arm holding a point-and-shoot camera. It’s the kind of shot that is taken by lovers and families on vacation. The conventions of this photography signify intimacy, fun, and play. In a later period when cameras became part of the smartphone - blurring the boundaries between video and still photography - they were termed selfies. But of course in the hands of Pigozzi this "intimacy" is in quotes and highly ironic. Secchiaroli’s feelings of bemusement and disgust for his prey, and for himself, are never far away from Pigozzi’s aesthetic. Where Pigozzi shines is his extraordinary use of focus. In "Mick Jagger and French Policeman Cannes, 2004" Jagger is out of focus while a policeman takes a flash picture in front of Pigozzi’s camera. The star is caught in a vise between snapping photographers while the true subject of the image is the decorative wall (circles) and fence (diagonals) in crisp focus that presumably separate and provide privacy. Jagger’s fame – sunglasses and neutral expression in place – beautifully sets the stage for Pigozzi’s magnificent image that brilliantly articulates the tropes of "privacy," in quotation marks of course, deployed like backdrops on a stage.

Edward Quinn, Elizabeth Taylor and Mike Todd at the Screening of Around the World in 80 Days, Cannes Film Festival, 1957

11.Edward Quinn

Edward Quinn is the most cinematic of the paparazzi – each of his images seems to be not just a film still but a film onto itself – a film closer in spirit to the charming and sensuous early work of Roger Vadim than to the artifice of Hollywood mega-spectacles or the complex self-reflexive realism of the French New Wave. Elizabeth Taylor and Mide Todd, Cannes Film Festival, 1957 shows Taylor wearing white gloves at the premier of her then husband, Mike Todd’s,’ new film, Around the World in 80 Days (1956). The photograph is of course far superior to the film itself and tells us much more about the realities of 1957. Todd’s film was a shallow, facile, exercise in entertainment and special effects, (in this Todd was ahead of his time), while Quinn’s image is a brilliant portrait of Ms. Taylor at the peak – or one of the peaks - of her beauty. She turns to look at something off frame sandwiched between two smiling men while her white lace dress and white head scarf turn her into a sexualized Madonna – but in a subtle way without the winking irony or self promotional zeal of Madonna Ciccone some thirty years later. The men seem to be in a party mood while Ms. Taylor looks to be very much her own woman. The dynamic self-assurance and sly intelligence that seem to radiate out of her quickly dispels any notions we might have had about submissive and repressed women in the fifties, handed down to us from cliché narratives and films, that persist to this day. Ms. Taylor’s white bag held tightly like a shield seems to glow and to mirror the white balls of light in the background of the modern interior, while the round lights act almost as musical motifs that balance Taylor’s self-assured, turning torso, as she aggressively scans the room.

Edward Quinn, Jane Mansfield, 1958

The resulting images by Quinn are among the most beautiful black and white images of the 20th century. As proof we need look no further than Jane Mansfield, 1958 showing the actress arriving at Nice airport and fighting her way down the rollaway stairs and into a crowd of fans and photographers. The image was not lost on Fellini, who also co-opted it for La Dolce Vita with Anita Ekberg playing the part of Mansfield - but Quinn’s image is better than Fellini’s scene. The chaos is not orchestrated for droll comedy (as in Fellini's film), and instead one can see in the various facial expressions and body motions a wide spectrum of emotional responses to Ms. Mansfield, including annoyance, curiosity, and, from the plane’s crew, complete indifference. Mansfield herself seems somewhat astonished and puzzled as she looks at an older man holding a microphone up to her like a space age phallus. The pleading hand at the bottom right of the frame from an unseen male fan brilliantly turns the spectacle into a pagan ceremony whose rules seem to be in the process of being formulated while the picture is being taken. Ms. Mansfield’s astonishment is at the center, but it is in the periphery - the reaction shots - where we find Quinn’s primary interest and focus.

Ron Galella, Robert Redford 1974

11. Ron Galella

Galella’s Robert Redford, 1974 showing the actor arriving at Mary Lasker’s (an activist for health causes) is a masterpiece done on the run – an iconic image of power, fame and beauty at mid- century. Mr. Redford is wearing a constricting dark jacket and tie, and aviator reflector glasses while getting out of a car. He is perfectly framed between windows: the one on the upper left shows a closed venetian blind that forms a series of delicate horizontal lines in counterpoint to heavy brick wall on the right. The curved window on the right from the car gives a distorted view of the street to the right as in a funhouse mirror. Redfords’ beautifully lit head is squarely between the two distinct surfaces. Reflections, glasses, the open door and the closed shades, are all frames within frames, windows within windows, that are no longer the object of a closed system but of gradations of open and closed, of privacy and exposure, that is the thematic subtext of the picture. Ron Galella’s primary interest is in power expressed physically in a body in movement within a restricted social space.

Ron Galella, Elvis Presley, 1974

Elvis Presley, 1974, shows the singer leaving a hotel, with his entourage and bodyguards, for a concert - all of them looking squarely into the lens of the camera. Elvis Presley looks like a gladiator wearing the jacket of a magician, full of macho bravado and puffed up with sexual energy, moving with supreme self-confidence through the air - an air that seems strangely tangible - as his arms spread outward, floating in space. Galella's photograph, with a security person in front, out of focus, is another brilliant study of male power on the move. Ron Galella can look at powerful people in the face and shoot – this in itself is quite unique - and links him to Salomon’s work in the early century. Both men were fascinated by power but Salomon wanted to capture history in the process of being formed almost as if it were a living organism – his approach is that of an ethnographer. Galella is interested in celebrity culture and its absurdities and charms. His camera doesn’t ask questions like Salomon’s but only observes with a certain envious complicity, like a teenager who wants to join the party but can only watch the adults drinking and flirting from a distance, and therein lies one crucial difference – another one is money.

Bertrand Rindoff, Getty Images, Nastassja Kinski and Roman Polanski 1980

12. How It Works

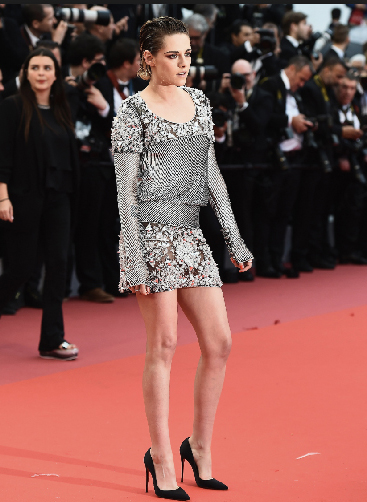

In 2010 a photograph of Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie on the red carpet at Cannes would be worth anywhere from $50.00 to $200.00 dollars. This very low amount is due to the fact that there are so many photographers getting the same shot and using digital cameras that shoot approximately 24 frames a second. A photographer who got a shot of Pitt and Jolie at their home, can sell this picture for approximately $10,000. Exclusive and one-of-a-kind pictures of Pitt and Jolie, taken clandestinely on the beach before they were officially a couple, fetched $250,000.00 to $500,000.00 (the figures vary depending on the journal). In the year 2000 OK magazine won the bid for exclusive rights to photograph the wedding of Michael Douglas and Catherine Zeta-Jones for 1.6 million dollars. This figure would have most likely been kept secret but another magazine beat OK to the event and published their pictures first – OK won the resulting lawsuit and the figures were made public.(36)

Edition of Documenti di Attualita, Exclusive pictures of Jacqueline Kennedy Nude, May 1972

Here is how it works. Most photographers sell their work through agencies that take 50%. The reason the agency can take such a hefty fee is that they have lawyers that can handle the grueling bidding wars between magazines for certain pictures, sign magnificently baroque contracts and secure a much higher fee than artists can usually generate on their own. If the agency has tipped off the photographer about locations or secret meetings the agency generally takes 60% to cover the costs of paying informants, bodyguards and drivers. The turnaround time between a photograph being taken and a final bid is usually 24 hours. An agency will send out low-resolution images with a watermark to prospective bidders and the bidding might start at $100,000 or more. The rest tends to happen quickly and lawyers from both sides make a deal to secure rights and protect against possible lawsuits. The language of the contracts is predictably verbose and arane to protect all parties against any possible contingency no matter how unlikely or obscure.

Keith Butler, Jennifer Aniston and Brad Pitt, 1999

Secchiaroli himself – as was also predictable – became disillusioned with paparazzi photography: “After ten years everyone was doing it and it was over. The provocations were happening all over the place, but they weren’t real – they were set up. By the mid 1960’s there were a hundred photographers around doing an imitation of the movie (La Dolce Vita).”(37) Secchiaroli’s complaint that it was no longer “real” feel somewhat out of touch - forgetting that he himself helped to pioneer this form of theater - but one also senses that he meant it as an emotionally honest retort to contemporary paparazzi who were purely mercenary businessmen doing a job, or worse, hacks playacting the role of “crazy paparazzi” just like in the movie. What he meant by “real” would have probably made a great book, but he never wrote it. For Secchiaroli – once the gofer boy at Cinecitta always on call – once a railroad worker shuttling between Rome and the provinces – the new breed of paparazzi must have been hard to stomach. After his work with Fellini that yielded his best work seen in a beautiful book titled Fellini, 8 1⁄2 he became the official photographer for Sophia Loren creating publicity photographs – not unlike the composite character of Marcello in La Dolce Vita writing “entertainment news stories” about films stars for a paycheck.

James Glossop, Paparazzi shooting the royal family in London from the press area, 2017

13. Retrospective

In 2007 at the Helmut Newton Museum of Photography in Berlin there was a retrospective exhibition of paparazzi photography that covered the period from Erich Salomon to Ron Gallela but nothing after that. The curator’s explanation for this gap: “Contemporary paparazzi images are consciously excluded from the exhibition, since it is hard to discern any real photographic quality in the flood of images shot by packs of photographers, whose methods have become increasingly ruthless and their equipment mechanized. Today, more so than ever, magazines and newspapers are highly interested in this kind of imagery. Regardless of quality and originality, it is sensation that counts.”(38) The curator seems to have romanticized the older generation of paparazzi at the expense of the new crop. Is there a real difference? I don’t think that sensation is any more prized today than when Garbo was being photographed almost a century ago – but as Debord says in Society of the Spectacle (1967) "...there is a greater sense of desperation now about the banalization of culture and the unity of misery that results from it."(39)

From a technical standpoint - what the curator referred to as "mechanized equipment" - telephoto lenses are now electronically controlled, as is the automatic exposure and focus. Once the pictures are taken the camera sends the images electronically to the company that the photographer is affiliated with; an editor then goes through them on a computer screen and decides which to use and which to file away. The paparazzi are now part of the institutionalized system of image production within the highly bureaucratic multinational media conglomerates and their more consumer friendly subsidiaries. It is hard to romanticize that. It is a tyranny with very little wiggle room – hence the frustration amongst the population at large and the resulting anger that populist politicians try to tap. That project known as "the paparazzi" is now very much engulfed by a glut of media images that must first pass through boardrooms, meetings with lawyers, and business lunches with execs on their wifi that decide their fate. The original mid-century paparazzi were amateurs in comparison – and a great deal of the charm of their images comes from their innocent and wholehearted - often heterosexual enthusiasm - for photography, and for beauty, that they shared. They don’t seem to have understood where it would all lead. Their improvisatory, fly-by-the-seat-of-your-pants, image scouting now seems, if anything, quaint.

Andy Warhol, Arnold Schwarzenegger, 1977

Anonymous photographer, Kristen Stewart on the red carpet at the Cannes Film Festival 2018

AP, Woody Allen With Paparazzi, 2012

15. Entanglement

Paparazzi photography today is directly related not simply to entertainment culture, such as it is, but to the construction of individual identities in contemporary society by all participants. Identities get entangled and no one is more aware of the amorphous quality of identity than people in the entertainment business. Paparazzi photography is now part of the world of publicity that dictates the terms of what constitutes identity and the “normal” per se for the population at large. For the paparazzi the amounts of money are far larger because the enterprise has a corporate underpinning to its enterprise from the outset. As John Berger put it “Publicity speaks in the future tense yet the achievement of this future is endlessly deferred...The interminable present of meaningless working hours is ‘balanced’ by a dreamt future in which imaginary activity replaces the passivity of the moment”(42)

This passivity of the moment is directly related to what Guy Debord called the “fragmented productive specializations which are actually lived.”(43) From the point of view of tyrants or tyrannical cultures, such as our current militarized corporate model, there is a great advantage to the population having a bad education, or none at all. Once an individual has no sense of her or his own identity, or history and their place within the larger Histories of mankind, something that they can manage - as Simone de Beauvoir put it as "a lifelong project" - they cannot form a coherent identity. This void – what Berger calls “the eternal present” - is now filled for us, whether we consent to it or not, by prefabricated images, sounds and words. That is where the paparazzi come in. The need to fill that void is enormous and generates large amounts of energy – and income – for a select few. How will those that have been denied their history react when, and if, they ever discover it? This is a question that the corporate culture is putting on hold – it’s their form of prayer.

Anonymous photographer, Kim Kardashian, 2016

16. Pseudo Events

Daniel Borstein – who coined the term “pseudo-event” in 1961 - helpfully explained how the significance and power of media events are in fact about the media - not the events.(44) Jean Baudrillard was saying something similar many years later when he insisted that the Gulf War - seen on television by millions of people - had in fact never taken place - that is the war itself had occurred but was not seen at all.(45) What was viewed by millions on television (or as Baudrillard called it: Telefission) was a narrative concocted by the American corporate state apparatus in confluence with the state department, the Pentagon, American media conglomerates and various other players.

While Daniel Borstein was morally repulsed by contemporary (1961) media culture, Marshall McLuhan, who wrote about many of these ideas, saw a great hope of some grand leap into a post Guttenberg (that is, post book) culture that would somehow incorporate the best of that “old” literary culture, and become a family - a “global village”– all living together in peace. Nevertheless what many people realized at the time was that Marshall McLuhan's promise of "instant simultaneity" created a paradox: that while this instant communication might provide an unheard of horizon of progressive and emancipatory experiences it also created a tribal sense of dread, both existential and generalized. The reason being that - as McLuhan himself makes clear - in a world of instant communication one can, at any moment receive a message that means: "Panic! Start running now!"(46) New means of transport and communication would create a permanent sense of dislocation and displacement as much as they would facilitate movement. The problems - clearly identified in the postwar period by writers as different as Albert Camus, Alberto Moravia, George Orwell, Hannah Arendt, and Herbert Marcuse were a rapidly diminishing human agency and political freedom, and the paradox that as human powers increase through technological mastery and humanistic inquiry, we are less equipped to control the consequences of our actions.

Anonymous photographer, Meryl Streep and Hugh Grant, at a film premiere, 2016

These unresolved paradoxes within the West created instability - and a sense of opportunity for the movement of capital for the elites, since the new electronic system of "instant simultaneity" would create a much more powerful, and interconnected, predatory capitalism. Under such a system greater wealth could be accumulated through electronic exchanges, which were fast, than through industrial production, which was slow. While there was common agreement that this was the situation at hand there was, as to be expected, radically different methods of finding a solution, if in fact there was a solution. What was understood was that the post-war utopian promises of universal access - via the computer, electronic communication and media, along with unlimited mobility, all presumably facilitated a new utopia, but, one that by the 1960's was in deep crisis.

Still, many people agreed, then (and now), with McLuhan's resplendent vision and see in technology a form of saving grace - a new religion. Since McLuhan’s concept of an interconnected and peaceful electronic Eden in the sixties Graeme Turner argues that presently (2009) there is a much more complex and sophisticated apparatus in place where “the celebrity turned into such an important commodity that it became a greatly expanded area for content development by the media itself. In a highly convergent media environment, where cross-media and cross-platform content and promotion has become increasingly the norm, the manufacture of and trade in the celebrity has become a commercial strategy for media organizations of all kinds – not just the promotions and publicity sectors.”(47) One can already read between the lines of Mr. Turner’s prose and see that it is a world dominated by agents, entertainment and media specialists, and copyright lawyers. Everyone else is just playing second fiddle even if they don’t know it.

Calvo Corrado, Rita Pavone (famous Italian singer and actress) in her garden, 2013

Richard Dyer in 1979 promoted the idea that the star system itself was a semiotic system that could be “read” as any other sign system within a field of cultural production that taps into power relations across classes within a society.(48) That Dyer's system would become popular in academe is predictable. His work is based on French cultural criticism of the 1950’s and 60’s – particularly that of Michel Foucault - that sought to turn everything exclusively into a language system controlled, and/or administered, by the state, or the ruling class - or some combination of the two. In this system people are exclusively social beings - interestingly this mirrors fascist rhetoric that also celebrates man as outside of, and superior to nature - one need only think of Filippo Marinetti's rabid Futurist manifestos exorciating the moon, nature and women - he preferred war and fast cars. For Dyer nature must be suppressed and marginalized, and for Marinetti it must be subdued and controlled. The epitaph of homo sapiens should read: "The animal that forgot that it was an animal." It would be a nice warning to intergalactic travelers of the future inspecting our small planet for signs of life.

Under this semiotic umbrella of humans as exclusively social creatures, celebrity becomes a battleground amongst the various factions within the ruling elite for what constitutes "reality." This semiotic plateau, from which we might survey the stars, is not without interest, but Roland Barthes got there first when he wrote about Greta Garbo in Mythologies (1955). Perhaps because he was writing about a particular star rather than “stars” perse, his work seems more poignant. Barthes: “It is indeed an admirable face-object”.(49) In this simple sentence, that we might pass over, he shows with great subtlety and humor his admiration for Garbo and his disgust at “Garbo.” They are part of the same movement toward and away from the screen where She makes her presence felt and Barthes explains that dichotomy, that sense of awe and betrayal, and those mixed feelings, in a way that contemporary theorists of fame have not come close to reaching.

There are those who, contrary to these ideas, see the proliferation of paparazzi photography, entertainment spectacles and mass media generally, as signifying a move toward a democracy of images – where the playing field is leveled and we are all famous for however many minutes we can manage to get depending on our charm, social skills, luck, and talent. As in any true democracy “the people” then decide and elect their stars. Social media sites such as Instagram insist on this "democratic vista." This viewpoint ignores – either by design or by default - the larger ideological narrative framework – the scaffolding - that holds photographs and various media suspended in prepared narratives indicating the corporate sponsor’s own predictable form of containment, control and management. This is Todd Gitlin: “Toward that end, each image is pre-stereotyped – designed as a tableau, a cartoon, so that without much effort the ensemble can be taken in at a glance and arouse the prescribed sensation.”(50) To think it would be otherwise is naïve as there is a lot of money at stake - the interests served are those of power and capital – of the banks, conglomerates and the financial aristocrats and oligarchs who own the images and the sounds. In our time the rest is just fantasy - moreover a fantasy of the lowest order because it is so shamelessly transparent - it isn't even a real fantasy but a "pseudo-fantasy" that conspires with a "pseudo-event" to create a "pseudo-reality."

®George Porcari 2016

1. Graydon Carter, Ron Galella, No Pictures (Powerhouse), 2008

2. Gus Macdonald, Camera: Victorian Eyewitness, A History of Photography: 1826-1913 (Viking Press), 1979

3. Gisele Freund, Photography and Society (David R. Godine), 1980

4. Photography and Society

5. Photography and Society

6. Photography and Society

7. Neal Gabler, Winchell: Gossip, Power and the Culture of Celebrity (Kopf), 1994

8. Alain Bergala, Weegee’s World (Bulfinch), 2000

9. Weegee, Naked City (Da Capo Press,) 2002

10. Weegee’s World

11. Photography and Society

12. Shawn Levi, Dolce Vita Confidential: Fellini, Loren, Pucci, Paparazzi, and the Swinging Life of 1950’s Rome (W.W. Norton), 2016

13. Angelo Restivo, The Cinema of Economic Miracles, Visuality and Modernization in the Italian Art Film (Duke University), 2002

14. Diego Mormorio, Tazio Secchiarol: Greatest of the Paparazzi (Abrams), 1998

15. Tazio Secchiarol: Greatest of the Paparazzi

16. Tazio Secchiarol: Greatest of the Paparazzi

17. Tazio Secchiarol: Greatest of the Paparazzi

18. George Zimbel, georgezimbel.com

19. George Zimbel, georgezimbel.com

20. Tazio Secchiarol: Greatest of the Paparazzi

21. Tazio Secchiarol: Greatest of the Paparazzi

22. Tazio Secchiarol: Greatest of the Paparazzi

23. Karen Pincus,The Montesi Scandal ( University of Chicago) 2003

24. Tazio Secchiarol: Greatest of the Paparazzi

25. Tazio Secchiarol: Greatest of the Paparazzi

26. Tazio Secchiarol: Greatest of the Paparazzi

26. Tazio Secchiarol: Greatest of the Paparazzi

27. Tazio Secchiarol: Greatest of the Paparazzi

28. Tazio Secchiarol: Greatest of the Paparazzi

29. Carol Squiers, Exposed: Voyeurism, surveillance, and the Camera Since 1870 by Sandra S. Phillips ed. (Yale University Press), 2010

30. Exposed: Voyeurism, surveillance, and the Camera Since 1873

31. Exposed: Voyeurism, surveillance, and the Camera Since 1870

32. Exposed: Voyeurism, surveillance, and the Camera Since 1870

33. Parker Tyler, Magic and Myth of the Movies (Simon & Schuster), 1970

34. Tazio Secchiarol: Greatest of the Paparazzi

35. Matthias Harder, Pigozzi and the Paparazzi: With Weegee, Galella, Angelli, Secchiaroli, Quinn and Newton (Helmut Newton Foundation), 2008

36. Pigozzi and the Paparazzi: With Aalomon, Weegee, Galella, Angelli, Secchiaroli, Quinn and Newton

37. Tazio Secchiarol: Greatest of the Paparazzi

38. Pigozzi and the Paparazzi: With Aalomon, Weegee, Galella, Angelli, Secchiaroli, Quinn and Newton

39. Guy Debord, Society of the Spectacle (Zone Books), 1995

40. Gary Lee Boas, Starstruck (Dilettante Press, 1999)

41. Richard Schickel, The Stars (Bonanza Books, 1962)

42. John Berger, Understanding a Photograph (Aperture), 2013

43. Society of the Spectacle

44. Daniel Borstein, The Image: A Guide to Pseudo Events in America (Harper), 1961

45. Jean Baudrillard, The Gulf War Did Not Take Place (Indiana University Press), 1995

46. Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media (Gingko Press), 2003

47. Graeme Turner, Understanding Celebrity (Sage), 2004

48. Richard Dyer, Stars (BFI), 1979

49. Roland Barthes, The Face of Garbo, from Mythologies (Hill and Want), 1972

50. Todd Gitlin, Media Unlimited: How the Torrent of Images and Sounds Overwhelms Our Lives (Metropolitan Books), 2001